Education Justice Program engages prisoners

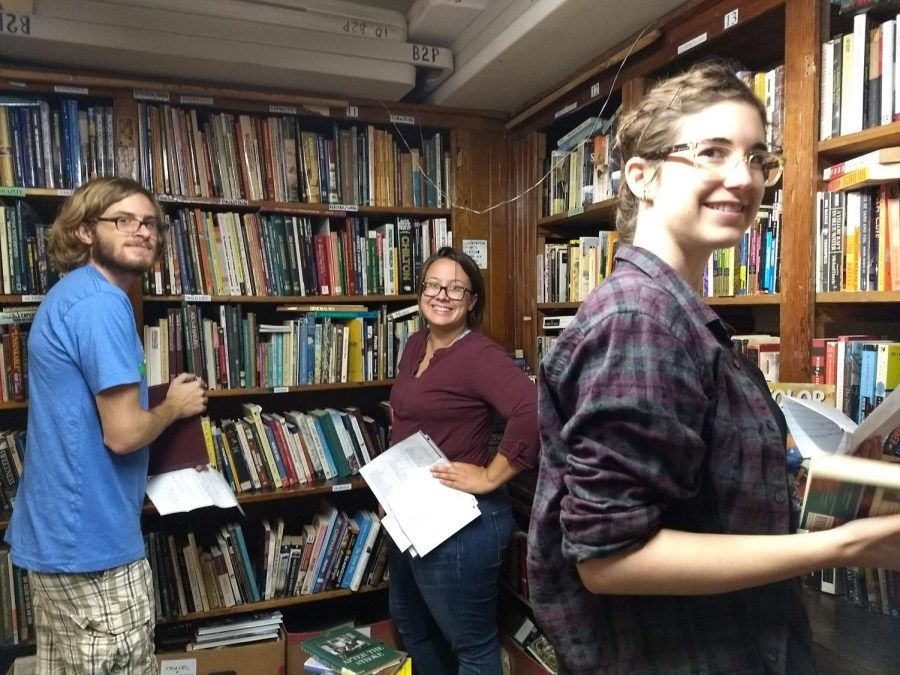

Photo Courtesy of Rachel Rasmussen

Volunteers pause for a photo in the basement of the Independent Media Center. The Education Justice Project is a college-in-prison program run by the University that offers upper-level university courses to inmates at Danville Correctional Center.

December 9, 2019

As prisons in Illinois continue to decrease spending on books and ban book titles, the gap between inmates and education and vocational studies widens. According to data from the Illinois Department of Corrections, only $276 was spent on books in 2017. This is a steep and progressive decline from the nearly $787,000 IDOC spent on books in 2002. A number of Illinois nonprofit organizations have stepped up in the meantime to provide inmates with access to books and education.

The Education Justice Project is a college-in-prison program run by the University of Illinois and co-founded and directed by Rebecca Ginsburg. University students as well as volunteers act as prison librarians and educators. The EJP’s programs are carried out in Chicago, Champaign and Danville, Illinois. The EJP offers upper-level University courses to inmates at Danville Correctional Center, conducts in-prison writing, math and science workshops and more.

Ginsburg said the EJP offers these programs to prisoners because of the importance and benefits of access to education on people and society.

“As part of a land grant institution, we see ourselves as an extension of the University of Illinois providing quality higher education to people throughout the state, understanding that it serves all of us in the state and beyond when they have such access,” she said.

The EJP has a number of success stories. Some students who were incarcerated without a GED or high school diploma have returned to society with bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“We think people who are in prison, no less than people who are out of prison, deserve as much education as they can take in and as much education as they want, and it turns out that many people who are in prison are wanting an awful lot of education,” Ginsburg said.

Recidivism refers to the return of formerly incarcerated people to jail or prison after being released. It costs the state of Illinois and its taxpayers millions of dollars every year.

In the summer of 2018, the State of Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council reported 43% of inmates return to prison within three years of their release. It also reported the average cost to taxpayers of a single recidivism event is $151,662. From the release of the report to 2023, SPAC predicts recidivism will “cost Illinois over $13 billion.”

Ginsburg said access to education in prisons is one of the few things that stands in the way of these figures.

“We know that our students have a lower recidivism rate,” Ginsburg said. “We know that our students get jobs more quickly than is average nationally. And we know that they get better jobs.”

According to a list compiled by the EJP, 202 titles were removed from the Danville Correctional Center, in January of 2019. Some of the titles included “Prison Grievances: When to write, how to write” by Terri Leclercq, “The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State” by Basil Davidson, “Respect in a World of Inequality” by Richard Sennett, and “The Color of Our Future: Race in the 21st Century” by Farai Chideya.

A significant amount of the titles are authored by black writers and are about race. Rachel Rasmussen, the volunteer coordinator at the Urbana-Champaign Books to Prisoners said the organization also faces restrictions from the IDOC on books pertaining to sexuality, sexual identity and LGBTQ+.

Rasmussen said these restrictions from IDOC stem from stereotypes about the LGBTQ+ community.

“The assumption is that any book about sexual identity means it’s going to be erotica,” Rasmussen said.

UC Books to Prisoners volunteers try to work around these restrictions by responding to these book inquiries with biographies of LGBTQ+ individuals and books on psychology.

UC Books to Prisoners uses its team of volunteers to respond to letters from the inmates in Illinois requesting books, completely free of charge. According to Rasmussen, the goal of the organization is to send books into prisons and engage the public on issues of incarceration and prison reform.

The positive effects of putting books into prisons is not measured only in numbers. Volunteers at UC Books to Prisoners have received many thankful, emotional letters from inmates since the organization’s beginning.

Some of the effects are on an academic level.

“We had a role in moving them from almost illiterate to earning an associate’s degree,” Rasmussen said. “One man sent us a copy of his GPA. He was so proud.”

And other impacts, Rasmussen said, are harder to record on charts and graphs.

“One (letter) that really moved me was a man who reflected on the fact that because of the reading that he had done, he had the insight that he himself had been a victim of violence,” Rasmussen said. “And that was why, in his own mind, he was kind of making a connection to his violence toward others.”

Education programs like EJP and grassroots organizations like Books to Prisoners are now facing more barriers than ever in connecting inmates with educational materials.

In recent years, at least 35 states have introduced digital tablets to prisoners. The introduction of new technology is supposed to make media such as books, movies and music more accessible to prisoners. However, The Outline reported recently that the tablets may make books more inaccessible to prisoners than ever before.

Companies like JPay and Global Tel Link, both corrections-related services providers, sell their tablets to inmates in 35 states across the U.S. Depending on the state, JPay entices inmates to purchase their tablets, such as at the JP5S and JP5mini, with features like downloading music and ebooks, email availability and access to educational materials. But all of these attributes come at a price.

Depending on the state and the correctional facility, a JPay tablet runs inmates about $69.99. And according to the New York state prison records, ebooks and audiobooks were costing inmates up to $19.99 per title, including those a part of the public domain up until Nov. 5 of this year. GTL charges inmates by the minute to access ebooks, music, video games and use video visitation with friends and family on the outside.

These rates are cost-prohibitive for reading and media materials that once would have been freely provided to inmates through funded prison libraries. Depending on how prisoners use the features of the technology, downloading music and sending emails can end up costing an inmate much more than it would a non-incarcerated person.

A current University student and former jail inmate for 18 months attests to the importance of books. For privacy reasons, she would like to be known only by her middle name Alyssa.

Alyssa said for many prisoners, reading is a form of “escape.”

“Reading was definitely the most therapeutic thing that you could possibly (in jail) do because it just takes you to another world and you don’t have to live in that one at that moment,” she said. “That’s how most people survived in there.”