50 years later, ‘Things Fall Apart’ is still required reading

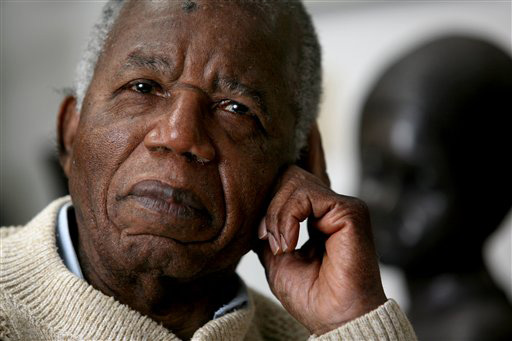

Chinua Achebe, Nigerian-born novelist and poet poses at his home on the campus of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York where he is a professor Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2008. Craig Ruttle, The Associated Press

February 14, 2008

ANNANDALE-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. – At age 77, author Chinua Achebe is living in grace and in exile, housed in a cottage built just for him on the campus of Bard College, lonely for his native Nigeria and the people for whom his stories have been written.

“I feel that’s where I should be,” he says of Nigeria, where he has not lived since the 1980s. “Having that relationship active, and working, is important for the health of my stories.”

A perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize and winner last year of the Man Booker International Prize for lifetime achievement in fiction, Achebe arrived at Bard in 1990, not long after an auto accident in Nigeria left him paralyzed from the waist down.

He is a longtime professor of languages and literature, and speaks warmly of the students who seem to know his work well, but Achebe has not completed a novel in more than 20 years, and has no desire to set any fiction in this country, saying it would not be “the most important thing for me to do, because there are so many people doing it.” While he is currently working on two or three projects, nothing is close to completion and he acknowledges that “a novel is certainly overdue.”

“This is a period that I found myself going to live abroad, and with the problem of paraplegia, which is not very comfortable. So just sitting down, writing a novel, has a huge physical side to it, which is not helped by this,” he says.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

He adds, firmly, “I must not deal with excuses.”

Still hoping to return to Nigeria, even though he has often dissented from the government, Achebe can look forward to renewed praise in the United States and beyond thanks to the 50th anniversary of his most famous book, “Things Fall Apart,” the rare modern novel to make history, and not because of any prize.

Achebe’s story of a Nigerian tribesman’s downfall before the advance of colonial power stands as the acknowledged birth of indigenous African fiction, an early and enduring literary portrait of a culture that had been seen only through the patrician stare of Western eyes.

An instant event in Nigeria but reviewed mildly in the United States when first published (the initial New York Times review ran less than 500 words), “Things Fall Apart” has been translated into more than 30 languages and sales top 10 million copies. No book by an African has been so deeply discussed or so widely influential.

“There were books by Africans before ‘Things Fall Apart,’ but this is the one everyone goes back to,” says Kwame Anthony Appiah, a leading African scholar who wrote the introduction to the Everyman’s Library edition of “Things Fall Apart.”

“It would be impossible to say how ‘Things Fall Apart’ influenced African writing. It would be like asking how Shakespeare influenced English writers or Pushkin influenced Russians. Achebe didn’t only play the game, he invented it.”

Interviewed recently at his home on a gray, snowy afternoon, Achebe sits at a small table in his dining room, the smell of fried fish tempting from the kitchen, a woman’s low humming (Achebe’s sister-in-law) soothing from another room. In front of him, like a conversation on hold, stands a glass of juice with a napkin draped over it.

The white-haired Achebe is a king in print, but he lives and dresses modestly, wearing a warm, white sweater and dark slacks. The art is in his speech: words spoken softly and carefully, with a sense of poetry and of oracle, a voice that makes you believe it could raise or resolve the most difficult mystery.

A native of Ogidi, Nigeria, Achebe was a gifted student whose father worked in the local missionary. After graduating from the University College of Ibadan, in 1953, Achebe was a radio producer at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation, then moved to London and worked at the British Broadcasting Corporation.

He was writing stories in college and was in London, in the mid-1950s, when he began “Things Fall Apart,” calling it an act of “atonement” for what he says was the abandonment of traditional culture.

The novel’s opening sentence is as simple, declarative and revolutionary as a line out of Hemingway: “Okonkwo was well known throughout the nine villages and even beyond.” Africans, Achebe had announced, had their own history, their own celebrities and reputations.

“I read ‘Things Fall Apart’ when I was a freshman in college. I was working full-time and taking classes and so busy it was scary and reading the novel fast and without much reflection I only thought it was OK,” recalls Dominican-American author Junot Diaz, whose books include the acclaimed novel “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.”

“It was when I read it again junior year, after my mind had matured some and I had read a number of other ‘African’ writers, that I understood the stupendous achievement of ‘Things Fall Apart’ and the sort of conversation it was having with other ‘African’ and European novels.”

The story is set around the turn of the 20th century and Okonkwo is a character as old as storytelling itself – a man who embodies a culture in decline, the virtues and the limitations. He is so wedded to the codes of battle and confrontation, the feats that led to his greatness, that he is tragically helpless before the modern power and persuasion of the missionaries.

In mockery of all the Western books about Africa, Achebe ends with a colonial official observing Okonkwo’s fate and imagining the book he will write: “The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger.” Achebe’s novel was the opening of a decades-long argument on his country’s behalf, in fiction such as “A Man of the People” and “No Longer at Ease,” and in essays dissecting the canon of the West.

He has attacked such popular works about Africa as Joyce Cary’s “Mister Johnson” as ignorant and self-satisfied. He was especially offended by Joseph Conrad’s “The Heart of Darkness,” once declaring it a “novel which … depersonalizes a portion of the human race,” reducing a great culture to a handful of threats and grunts.

“Now, I grew up among very eloquent elders. In the village, or even in the church, which my father made sure we attended, there were eloquent speakers. So if you reduce that eloquence which I encountered to eight words … it’s going to be very different,” Achebe says during his interview.

“You know that it’s going to be a battle to turn it around, to say to people, ‘That’s not the way my people respond in this situation, by unintelligible grunts, and so on; they would speak.’ And it is that speech that I knew I wanted to be written down.”

Achebe writes and thinks to contrapuntal melodies of language and culture. As a child, he was schooled in the stories of his relatives and in the English literature of the colonialists. In his mind Ibo legends and the prose of Dickens still meet, the “two types of music” that sometimes clash and sometimes converse.

“What I found myself doing more and more, whenever I encountered a statement I thought was interesting or profound in one language, I would try to put it into the other language to see if it would work,” he says.

His novel is a triumph of contradictions: a memorial for a tribal culture by an author whose father was a convert to Christianity; a history-making book about a man whom history left behind; a document of a preliterate people written in the finest contemporary prose.

“There is a proverb that the sword you have is the one you greet your peers with,” Achebe explains. “Is it (a novel) the best weapon? Of course, not. If that’s what you can do, then offer what you have. You know that there may be better things to offer…. It’s what I can manage. It’s not adequate, but that is what I have, so please accept.”

Appiah says that language is part of the genius of “Things Fall Apart.” He notes that earlier novels by Africans, including Amos Tutuola’s “The Palm-Wine Drinkard,” were written in a kind of Africanized prose that seemed to mimic the way a Nigerian would speak English.

“What Achebe did was answer a question no else had thought of asking,” Appiah says. “The problem was: If you’re going to write about Africa, how do you write about all the different people and cultures and do it through the language of the novel? He solved the problem by drawing on different levels of English, from slang to the most precise 20th-century realism. Once he had showed you how to solve the problem, it all seemed so obvious.”

One of the most celebrated young Nigerian writers, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, says that she read “Things Fall Apart” when she was around 8 and has periodically reread it. “I find that I liked the same things each time – the familiarity with it. I hadn’t realized that people like me could be in a book,” she explains.

Countless others have cited Achebe, from Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, who once called “Things Fall Apart,” a “major education” for me, to Ha Jin, a Chinese-American novelist. Achebe himself recalls some letters he received about a decade ago from students at a women’s college in South Korea.

“It surprised me also in the sense I realized that people in different places would be reading it from totally different positions, positions I didn’t think they knew about,” he says.

“They (the students) said to me, many of them, that this was like their story. And I said to myself, ‘Korea? I don’t know Korea. And I don’t know what their story is.’ They explained that they were also colonized, by the Japanese. That simple fact of colonization was enough to make someone so far away come to terms quickly with this story.”