Textbook packaging raises price

Travis Austin

May 2, 2006

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a three-part series about the increasing cost of textbooks. Part two will run Wednesday and will focus on the impact the increasing prices have on students. Part three will run Thursday and will focus on what is being done by students and legislators to combat rising textbook prices.

With higher education costs on the rise, the price of textbooks is a growing concern for students, parents, educators and state officials.

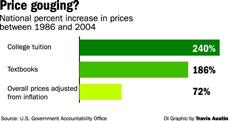

Textbook prices increased 186 percent between December 1986 and December 2004, according to a Government Accountability Office report released in July 2005. Overall prices inflated just 72 percent during that period.

“It is important that businesses are able to make a fair profit, but students should not be forced to buy expensive books and items that are not even required course material,” said Rep. Naomi Jakobsson (D-103) in a February press release.

Those familiar with the textbook market cite the practice of bundling as a main cause of the price increase. Bundling is the packaging of textbooks with study guides, CD-ROMs and other materials that are sometimes not required or used by professors.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

According to a report released in February 2005 by the State Public Interest Research Groups, half of textbooks surveyed were bundled. Fifty-five percent of bundled books were not available unbundled.

Sixty-five percent of faculty surveyed said they “rarely” or “never” use bundled materials, according to the first edition of the report, which was published by the California Student Public Interest Research Group in January 2004.

University economics professor Fred Gottheil likened the increase in textbook prices to the increase in medical costs. He said the price is justifiably higher due to better technology, including study guides, online materials and videos that were inconceivable when he purchased his first economics textbook for $5.50.

“All that stuff adds to the cost, so that when you buy a textbook, it’s not really a textbook, it’s a textbook with supplemental material, packaged together. It’s like health care, so much more than you had before,” said Gottheil, author of microeconomics and macroeconomics textbooks that are used by hundreds of University students each semester, and students on 200 other campuses.

“If someone took advantage of all the stuff that we give them, my God, what an understanding of economics they could get, what a training, if they did all that,” he said.

The price of publication

Director of general chemistry at the University, Paul Kelter, has worked to help make textbooks in his program more affordable. Kelter is also the author of “Chemistry: A World of Choices,” a 700-page textbook for non-science majors.

“The question of what something ought to cost is a moving target,” Kelter said.

From conception to publication, the development of a textbook costs approximately $1.5 to $2 million, he said.

The author is typically paid an advance of $10,000 to $20,000.

Editors are paid approximately $20,000. After the manuscript is complete, about 60 reviewers read each chapter; each is paid $60 to $100.

With subjects like chemistry, other professors are then paid about $20,000 to write end of chapter problems and solutions. Publishers then pay artists and photographers for producing photos, illustrations and graphics. They also pay fees for any figures, charts, photos or artwork from other sources.

The book must go through compositing so it can be printed. The compositing process is so expensive that many companies now outsource the work to India.

Once the manuscript is complete, it goes through three accuracy reviews before being printed.

When the first edition is finally published, sales representatives convince professors to adopt the book. Publishers also conduct research to ensure their book appeals to professors.

This can be very difficult because professors are often loyal to the books they are already using, Gottheil said.

The costs of producing supplemental materials add to the total. Often these items are added at a price just enough to cover their production, Kelter said.

Gottheil explained that profit margins made by textbook publishers are similar to those earned in most other industries.

“I’m one of the success stories . a lot of guys who start writing a textbook never see it in print,” he said. “There’s a lot of up front expenses.”

On the shelf

Once a professor has adopted a book, it must be stocked by campus bookstores.

The publisher generally determines book prices, said Willard Bredfield, director of the Illini Union Bookstore.

Since 1941, the Illini Union Bookstore has sold textbooks to students at discounted prices. The store has a discount of four percent for new books and 29 percent for used books. It also guarantees lower prices than other campus bookstores.

“We actually send someone out to guarantee the price,” said Bredfield, who has worked at the bookstore for 28 years.

The store also makes sure that the books are always available at advertised prices.

Another role of campus bookstores is buying and selling used textbooks. The price the Illini Union Bookstore pays for used textbooks depends on faculty orders for the next semester.

If an order has been placed, the bookstore will pay 50 percent of the current price, whether the book was purchased new or used.

If a book has not been re-ordered, the bookstore employs a used book dealer who pays the student based on the demand of the book across the country. This offer can range from zero percent to 35 percent of the current price. The dealer then stocks the books in their warehouse for use on other campuses.

“The used book business is a very speculative business,” Bredfield said.

To meet student demand, bookstores must purchase additional used books from a dealer.

The Illini Union Bookstore sells used textbooks at 75 percent of the current price for the new version.

Doing some good

The profits from some textbooks do not go back to the authors, publishers and retailers.

“One hundred percent of the (bookstore’s) proceeds go back to the Illini Union to support student programs and activities,” Bredfield said. “It stays within the University.”

Royalties from Gottheil’s books go to support the Josh Gottheil Memorial Fund for Lymphoma Research. The fund was set up in honor of his son, who died of Lymphoma in 1989.

A number of publishers were interested in publishing a textbook by Gottheil after he wrote a sample chapter in the mid ’80s, he said.

When his son died, he saw the textbook as a way to both honor Josh and his friends and raise money for a memorial fund.

He said he became obsessed with writing the book and was able to include the names of many of his son’s friends in the various stories used as examples in the text.

“I honestly don’t think I would have ever written a textbook had this not happened,” Gottheil said.