UI dedicates plaque to chemistry student

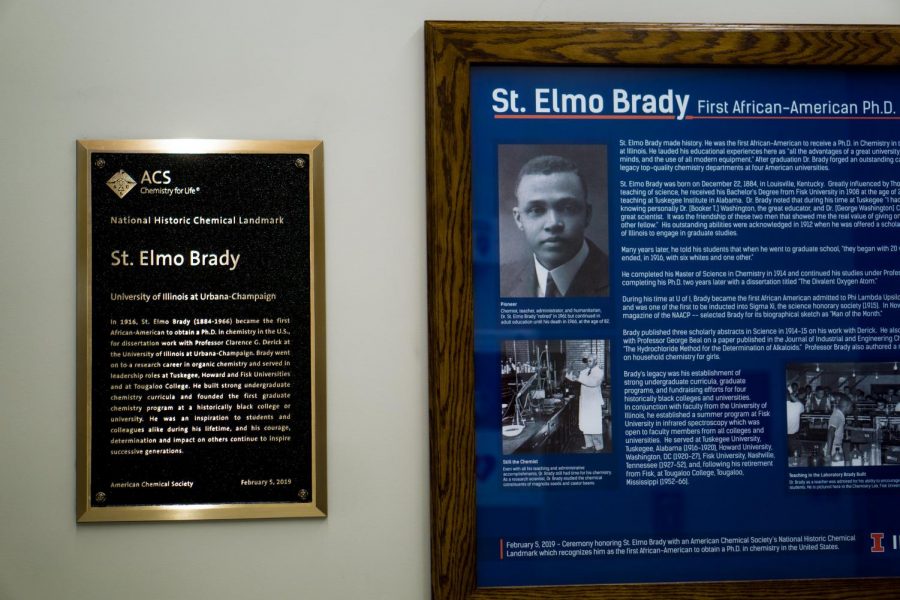

A bronze plaque dedicated to St. Elmo Brady in Noyes Hall on Monday. St. Elmo Brady was the first black student to receive a doctoral degree in Chemistry in the U.S.

March 7, 2019

The legacy of St. Elmo Brady, the first black student to earn a chemistry doctoral degree in the U.S., has been unearthed by the University during Black History Month after awarding a bronze plaque and an exhibit in his honor.

The plaque honoring Brady is located on the first floor of William A. Noyes Laboratory, a National Historic Chemical Landmark as designated by the American Chemist Society.

The exhibit, curated by University archivist Jameatris Rimkus, is open to the public on the first floor of the Main Library, in the hallway and inside the University Archives, and will continue to be available through March.

“In 1916, St. Elmo Brady (1884-1966) became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry in the U.S. for dissertation work with Professor Clarence G. Derick at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign,” the first sentence on the plaque states.

The exhibit contextualizes Brady’s achievement. In 1914, Brady earned a scholarship to begin his doctoral studies at the University.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Prior to enrolling in the University in 1913, he had completed his undergraduate studies at Tuskegee University. He earned his master’s degree in 1914, and two years later finished his doctoral degree with a dissertation titled “The Scale of Influence of Substituents in Paraffine Monobasic Acids. The Divalent Oxygen Atom.” According to the American Chemical Society, he is the 40th graduate of the chemistry doctorate at the University.

The Daily Illini’s April 25, 1914, issue mentions Brady’s participation in the YMCA Auditorium in a talk on his work at Tuskegee.

On April 14, 1915, another article mentions Brady among a group of 40 men inducted to Sigma Xi, an honorary scientific fraternity. He was one of the first African- Americans to be inducted to that honor society as per the American Chemical Society. Previously, he had joined Phi Lambda Upsilon, a chemical honor society founded at the University in 1899.

On April 24, 1923, a report stated Brady had been designated as a member of the editorial board of “Howard Review,” a magazine meant to encourage scholarship among African Americans.

Another article from The Daily Illini dated Oct. 21, 1923, describes the Howard Review as, “a new thing in the realm of scientific periodicals.”

Brady helped to create Howard’s graduate program in chemistry where he worked from 1920 to 1927; he went on to chair Fisk’s Department of Chemistry from 1927 to 1952.

“He choose to educate … essentially taught since he graduated until the time he died,” Rimkus said.

While he was at Fisk, the Infrared Spectroscopy Institute was formed. A letter from Betty Fisher, a student of Brady’s, is also included in the exhibit in the context of his retirement from Fisk.

“The experience, guidance and knowledge which I have obtained from you as a teacher and friend will always be a part of my life’s memories,” Fisher wrote.

Brady’s granddaughter, Carol Brady-Fonvielle remembers him as gentle, loved, patient and a builder.

“He opened the world of chemistry to students of color. He let students know that their dreams are possible … he was a terrific grandfather,” Brady-Fonvielle said.

During the last 14 years of his life, he was dedicated to the advancement of chemistry at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi. Prior to his death in 1966, he was studying treatments for cancer and malaria, according to the American Chemical Society.

The exhibit also notes that besides being an accomplished professor, he was a practical man who created formulae for everyday needs such as hair lotion and mosquito repellent.

“He was known for his ‘chalk and talk’ examinations, and while he could strike fear into the heart of the boldest senior, he was soft, gentle and never raised his voice,” said Brady’s friend, Samuel P. Massie from the United States Naval Academy in 1967.

In 2016, a century after his graduation, the total number of African American students enrolled on campus was 2,317 out of a total of 44,880 students, 5.16 percent of the student body. A total of 35 students were enrolled in chemistry programs in 2016, stated a report by the Division of Management Information.

“There is still a great need to increase underrepresented students in STEM fields,” said Ronald Bailey, director of African American Studies.