The Morrow Plots: A hidden campus gem

The Morrow Plots, located between the South and Main Quads, are the oldest experimental crop fields in America and the second oldest in the world.

May 24, 2023

When one thinks of iconic campus locations around the University, students typically consider the photogenic Main Quad or Alma Mater as contenders — the nondescript plots of farmland across from the Main Library might not be the first thing that comes to mind.

The importance of these titular Morrow Plots is almost always left a mystery until students run into the countless rumors that swirl about the ordinary-looking field.

“I know what they are because I have to walk past them sometimes,” said Akshar Goyal, freshman in Engineering. “I heard that if you walk on them, you would be immediately expelled.”

While the myths around the plots are colorful, with some considering a stroll through the fields at the stroke of midnight before graduation as the ultimate challenge, they pale in comparison to the Morrow Plots’ true significance to agricultural history and global farm innovation.

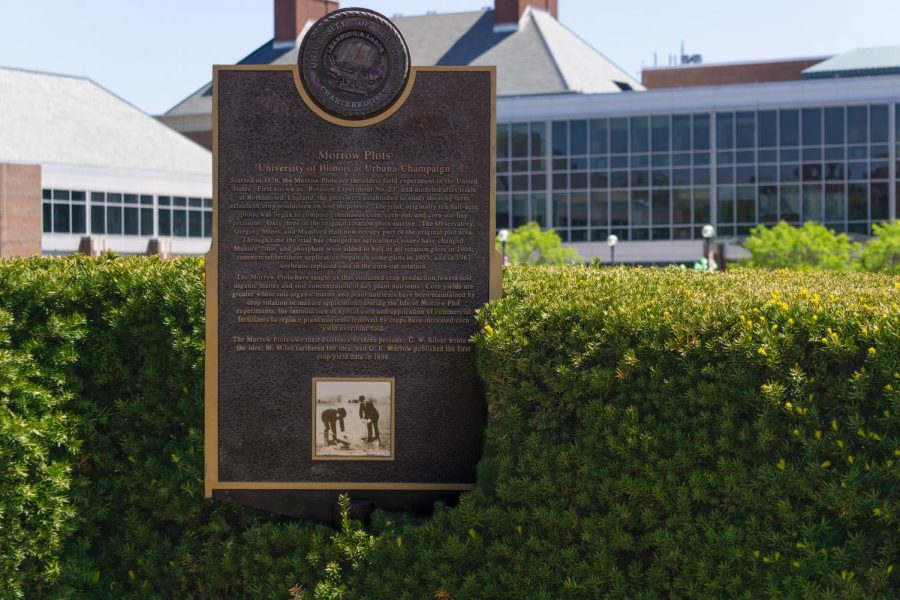

The Morrow Plots are America’s oldest, and the world’s second-oldest, continuous agricultural experiment. Founded in 1876 by professor Manly Miles, only nine years after the University was established, the plots were a hotbed of innovation in the field of agricultural science.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The discovery of many valuable agricultural breakthroughs, such as the positive effects of crop rotation on soil fertility, are credited to the plots. While only three of the original 10 plots remain, this recognized National Historic Landmark is still used for research to this very day.

“People don’t realize what a rare resource we have,” said Andrew Margenot, current head of the Morrow Plots Committee. “Very indirectly, lots of insights from the plots are broadly applicable to crop production anywhere in the world.”

The plots still impact the agricultural industry with its long-term value as experimental farmland. According to Margenot, he continues to receive requests from researchers across the country looking to utilize the Morrow Plots.

“When I was at University of California-Davis, we would hear about the Morrow Plots … other agriculture schools that are top in the world salivate talking about the plots,” Margenot said. “We can answer questions about sustainability, such as the long-term effects of fertilizer, that cannot be answered by many shorter-lived studies.”

Sandi Caldrone, a research data librarian at the University Archives, expressed her own perspective on the plots’ significance in the world of data visualization and analysis.

“I don’t have any background in agriculture, but I find the plots absolutely fascinating from a data science perspective,” Caldrone said. “It’s not often that you find a dataset that spans 100 plus years … the end result is really ideal for students in any field who want more experience using real data.”

The plots themselves have an unusual record of ruin within the university. A plan to “cream,” or destroy, the corn grown in the Morrow Plots as a student protest against the Vietnam War was nearly successful. In 2003, the plots were vandalized with a manmade crop circle.

Despite its checkered past, the Morrow Plots continue to foster advancements in agriculture as it approaches its 150th anniversary in 2026.

“It’s really an honor to be a part of this,” Margenot, who has headed the committee for the past half-year, said. “These plots predate my family’s entrance into the American homeland … Someone has been doing that exact same thing for 147 years, for every single season, with the same planting on the same plots.

“There are black-and-white photos of people working out there. It’s a sense of connection to the past.”