CU sees large increase in Cooper’s Hawk population

April 10, 2014

Back in the ‘80s, Avian Ecologist Mike Ward would look up to the sky near his home in Springfield, peering out for a specific type of bird — the Cooper’s hawk. But he rarely ever saw one.

Now he sees one everywhere he goes. A Cooper’s hawk is nested across the street from his house and nearly every day, he spots one outside of his office window on the fourth floor of Turner Hall. Apparently, these birds have made a major comeback since the ‘80s, even in urban settings, said Ward.

And it’s not just avian ecologists who are noticing this.

A pair of hawks have set up a nest in the middle of Champaign local Sue Anderson’s backyard in a big oak, and have since become the block’s new buzz topic.

“It draws neighbors together and we’ve had several group conversations to figure out what they are,” Anderson said. “Sometimes we just watch them. It’s kind of fun.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The hawks have been narrowed down to two species: they’re either Cooper’s hawks or Northern Harriers. Regardless, Anderson’s next-door neighbor, University graduate student Paul Littleton, says he’s “honored” to have the hawks nest near his home.

“There’s habitat available in our neighborhood that’s suitable for the hawks,” he said. “It’s just a reflection on the environment.”

Ward, who works at the Illinois Natural History Survey and serves as an associate professor at the University, said historically, Cooper’s hawks have been persecuted by humans.

“Back in the ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s, when people had chickens in their backyard, people would typically shoot Cooper’s hawks to keep them away,” Ward said. “So at some point in time, there was obviously some pressure for Cooper’s Hawks not to be in towns.”

This was true even as far back as 1906, when a University alum, Alfred Gross, conducted a survey of the hawk in Illinois.

“90 percent of damage done by hawks may be properly accredited to (the Cooper’s hawk),” he wrote in his notes. “And with his perverted taste for chicken, (the hawk) becomes a menace to the country.”

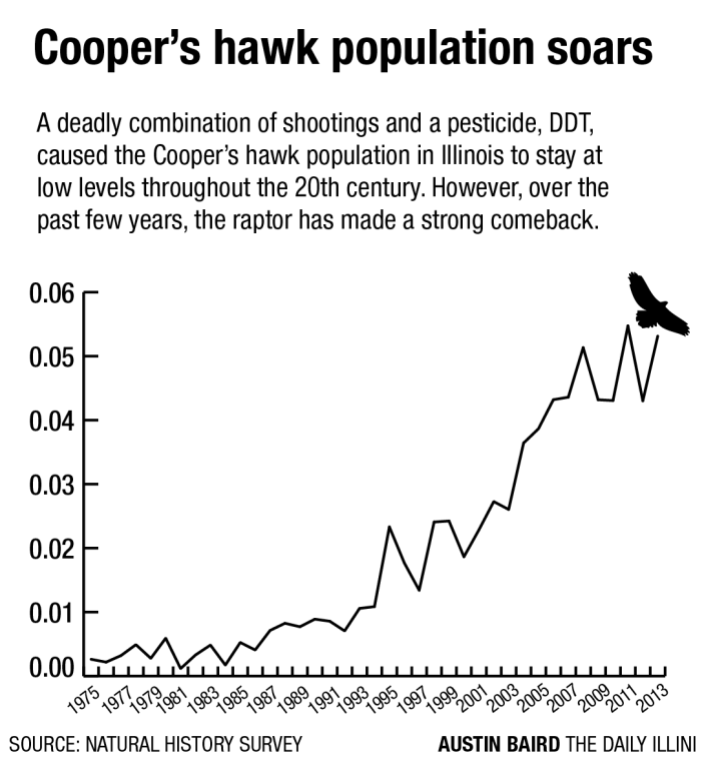

The data Gross and his team collected showed low levels of the Cooper’s hawk, and these low levels persisted throughout most of the century. Ward said this was most likely due to the persecution.

Then an insecticide known as DDT came along. Ward said it reduced the calcium in bird eggs so that during incubation, many would crack.

“It didn’t help,” he added.

But come 1996, the population began to bounce back and the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board took the Cooper’s hawk off the endangered species list.

“The first nests I saw were in suburban forest reserve types of places,” Ward said. “Then they quickly started showing up in people’s back yards. And so, I think they just figured it out, I mean why not nest in somebody’s backyard?”

He added that as communities in Illinois matured, so did their foliage — like the large Oaks in Anderson’s yard.

“Our urban areas are much more similar to forest habitats than they were years ago. And so as these trees get older, there’s essentially a forest community without the understory,” he said. “It’s ideal for Cooper’s Hawks and other raptors as well.”

Anderson began to notice an influx of hawks in Champaign-Urbana around five years ago, but now that a pair has moved into her backyard, she has mixed feelings.

“On the one hand, any type of large bird is an amazing creature,” Anderson said. “On the other hand … it may keep other birds out of my yard.”

Birds, like Mourning Doves or Robins, that would normally come to Anderson’s bird feeder might shy away from the area because the hawk is their predator. And the recent societal drive to naturalize urban areas, Ward said, is partially why the hawk populations are increasing.

“A lot of people plant native plants, they leave a little area in the back for the birds and the mammals and stuff,” he said. “It was not too surprising that if we want all these small birds, obviously their predators are going to come along.”

And the Cooper’s hawk, Ward said, is just the first. He predicts that Red-shouldered hawks, Merlins, and eventually Swallow-tailed Kites, will see an increase in population.

Ward said that Champaign-Urbana hasn’t really reached “saturation” yet, meaning the area hasn’t reached its limit on predator birds. But when saturation does occur, hawks will meet a kind of equilibrium due to their fierce territorial nature.

“If you don’t have a hawk around your neighborhood, you will soon.”

Austin can be reached at [email protected] and @austinkeating3.