Latinx communities experience additional stressors

September 23, 2019

For many in Latinx communities, because of traumatic migration experiences and the almost constant threat of deportation, anxiety and fear can define their everyday lives.

For these communities, many have lost a sense of belonging. This leads to a fear of possibly being separated from friends and family.

Fatima Castillo, junior in LAS, said the U.S. president and his administration are causing substantial anxiety for not only the Latinx community, but also other minority groups.

“This is like Trump’s America right now, which really sucks,” Castillo said. “Especially now it’s him making it so that racism and hatred are really becoming prevalent and coming out, being brought into the light. It really does make people in the Hispanic community and other communities very, very anxious.”

Mikhail Lyubansky, teaching associate professor in LAS, said the current political climate brings a unique stressor to Latinx communities.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“From a political climate in which part of the mainstream political rhetoric from one side is you build a wall and everything goes with it, which is targeted to very specific groups,” Lyubansky said. “So, that’s a unique stressor for those who are in this country from a very particular place.”

Julie Dowling, associate professor in LAS, said Latinx immigrants, especially those who are undocumented, face considerable stress, especially in the current climate of anti-immigrant and anti-Latino sentiments.

“Anti-immigrant rhetoric in the media, government raids on immigrant areas, and violence against Latinos such as the recent El Paso shooting all contribute to feelings of anxiety and fear for Latinos,” Dowling said in an email. “This has important consequences for physical and mental well-being.”

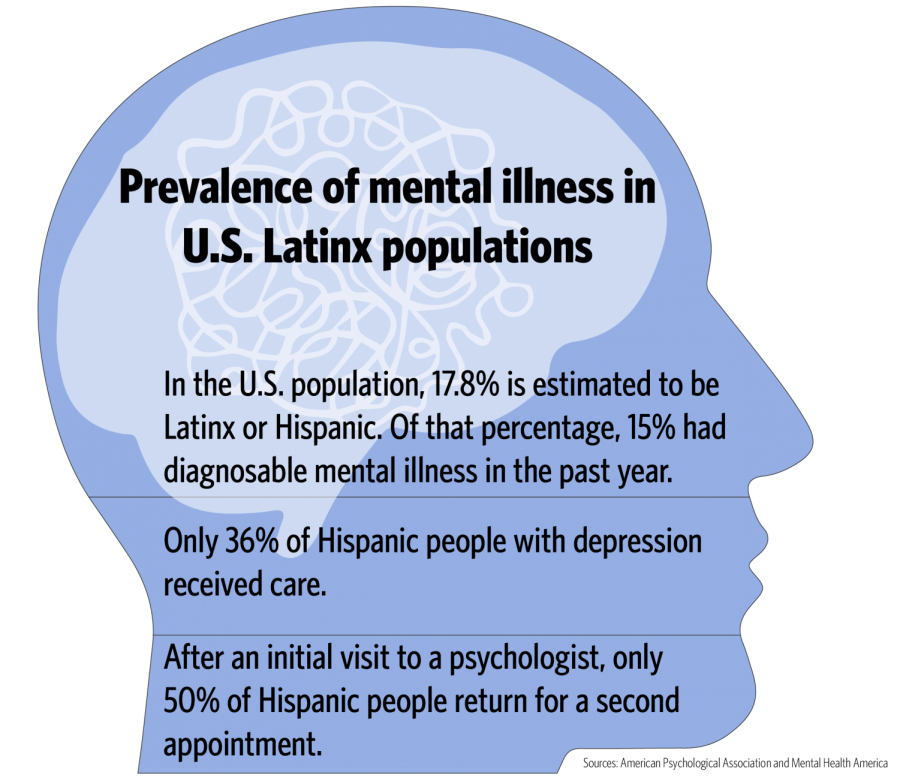

With these stressors on the table, mental health issues can still be neglected due to lack of resources and cultural stigmas.

Castillo is a second-generation immigrant, and she grew up with her parents who are from Mexico. Castillo said she is anxious for her father, who has yet to renew his green card. Application for renewal alone will cost Castillo’s father over $500 without guarantee of a reinstation.

While he is not targeted by the ongoing Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids, being employed in construction and working alongside undocumented immigrants heightens his chances of collateral deportation, Castillo said.

“It’s, like, incredibly anxious knowing that the people that I know and people (in my own household) can be threatened and deported for just trying to put themselves in a better situation than it is being back their home country,” Castillo said. “And I usually try not to think about it, but it’s important to talk about, because avoiding it isn’t going to do much. So talking about it and making sure that people are aware of it knowing their rights is, I feel, very important.”

Lucia Maldonado, Latino Parent Liaison of Urbana School District 116, migrated to the U.S. with her two young children. Barriers of language and culture lead her to feel frustration, and today it serves as motivation to help those in the community who are struggling to adapt as she did 26 years ago.

Without services for Latinx parents, Maldonado said she felt the need to connect Latinx households and schools to lessen the stress a parent can feel about visiting their child’s school.

“Some of the things that I started doing really changed that, and just the fact of letting people know that there was one person that they could call when they have questions, I always place myself in their shoes, because I was in their shoes years ago,” Maldonado said. “So just knowing that you have somebody to call makes a huge, huge difference.”

Working at the school district, Maldonado said she has seen heightened stress and anxiety within the last three years, not only in parents, but also in young children, afraid for their future in the U.S.

“Right after the president got elected, I started getting requests from teachers to talk to students and to check in with students because teachers were concerned,” Maldonado said. “Students started sharing concerns here about not only themselves and their future, but about their parents.”

A student in Maldonado’s district wrote an apology for his poor performance on an essay, adding that he could not focus while living in fear of being separated from his parents.

“These are kids,” Maldonado said. “So, to me, knowing that most families train their kids really well about not talking about anything related to immigration law, don’t answer any questions related to immigration, don’t talk to anybody about any of that; the fact that students were breaking that rule. They were talking to people and, in many ways, asking for help really was a big sign.”

Despite the need for mental health care to cope with these heightened feelings of stress, discussion on the topic is often avoided in Latinx communities.

Lyubansky said internalizing stress can lead to depression, anxiety and other mental disorders. The critical question to be asked in these cases, he said, is the presence of support from family and community awareness that behavior rooting from experience is not simply laziness or being ‘crazy.’

“In many immigrant communities, there’s more stigma,” Lyubansky said. “There are lots of stigmas here in the U.S., but in many of the immigrant communities, there’s even more stigma. So there isn’t a place to really engage that.”

This summer, Castillo worked as an intern at Esperanza Health Centers in Chicago at a clinic that provides bilingual counseling services for Latinx communities. To lessen the stigma and hesitation of seeking help, Castillo said psychologists would avoid utilizing their official title and instead describe themselves with the word “counselor.”

“It’s very much being too prideful and being looked down upon,” Castillo said. “It’s like ‘You’re being weak for not being able to work out the stuff in your head,’” Castillo said.

Maldonado said much of the Latinx community avoids discussing mental health.

“It’s one of the topics that is actually avoided,” she said. “There is also a huge stigma in the Latino community. We have had children who are depressed, who are probably clinically depressed, but their parents keep thinking or keep saying that they’re just tired, that they’re just bored that they’re choosing to be that way.”

Despite discussions about immigration and ICE arrests increasing in frequency, Maldonado said she does not want the discussion of fear to become normalized and desensitized.

“I don’t want to take any of the (harshness) from any of those topics, but I want to make sure that people know that they can talk about it, that we can talk about it,” she said. “I want to make sure people know that they have someplace to go and that they have options.”

Gloria Yen, director of the New American Welcome Center at the University YMCA, said even if there were sufficient resources available, conversation is a significant factor in approaching the issue in the long-run.

“It’s a really important conversation to have in terms of just normalizing mental health as a part of your (overall) health,” Yen said. “Also that you’re not the only person in this scenario and that it’s something that is a benefit for everybody, immigrant and otherwise, to pursue (is important to remember).”

Seeing Latinx community members living with increased stress without seeking mental health support is not only the fault of cultural stigmas, but also a lack of resources.

With very few bilingual counselors that can provide the right advice on culturally sensitive topics, Maldonado said she can only hope those in need will try to survive or become mentally stronger.

“What does that do to your body, to your mind, to your soul living like that and not knowing how long you’re going to be able to stay with your family, not knowing if one of your own is going to be picked up?” Maldonado said. “Some people avoid thinking about that. Most people think about that every single day.”

Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo, professor in AHS, conducted research focused on prenatal Latino mothers and the effects of immigration and deportation on their mental health.

Due to psychosocial factors such as poverty and discrimination along with other cultural stressors, Lara-Cinisomo said Latinas are a high-risk population for experiencing perinatal depression compared to women of the general population, yet the topic is highly understudied.

“We need to create resources at the community medical health care and national level that is going to support these women who make the sacrifice of coming to this country to seek a better livelihood for themselves and their family,” Lara-Cinisomo said.

With limited federal opportunities and funding to conduct research on Latinx populations, Lara-Cinisomo said an emphasis on creating safe spaces in the community to discuss mental health needs is crucial.

“Your immigrant status should not be a factor of whether or not you can talk about your mental health and your mental health needs,” Lara-Cinisomo said.

Lyubansky said people who migrate to the U.S. are, on average, healthier than U.S. born citizens.

“We should be concerned with the mental health of immigrants for the same reason we’re concerned about the mental health of non-immigrants,” Lyubansky said. “It’s just the human compassion piece. People are suffering, so we ought to care about their suffering. Just the reminder that this is a country of immigrants, it’s all of us, unless you’re talking to somebody who was part of the indigenous communities of North America. The rest of us are immigrants or descendants of immigrants. It’s us; we want to take care of ourselves and each other.”