Opinion | Remembering the lost Beatle Elliott Smith

Courtesy of Nils Breunese / Flickr

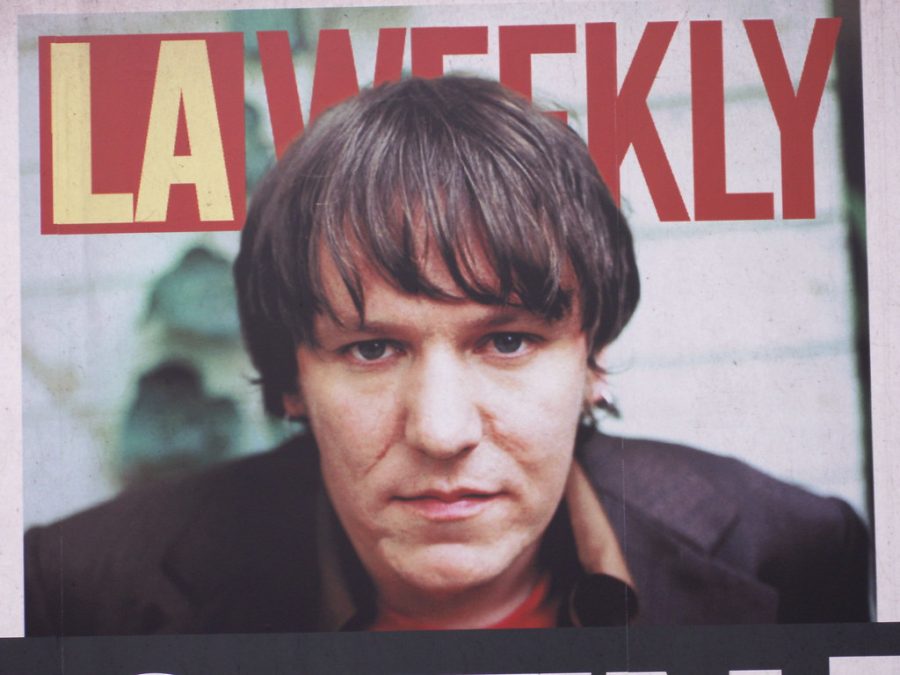

Elliot Smith on the cover of LA Weekly. Senior columnist Eddie Ryan explores the legacy of Smith’s honest and expressive songwriting.

May 9, 2023

All Elliott Smith fans have a favorite Elliott Smith clip. Mine is poignant; it somehow seems to capture so many sides of him in one tortured, beautiful instant.

Cigarette in hand, Smith gives his philosophy on failure to an interviewer in his characteristically off-the-cuff but incisive manner.

“Playing things too safe is a popular way to fail,” Smith says. “Dying is another way … or, like … killing your emotions is another popular way … with, you know, drugs or alcohol or whatever.”

When asked if he is succeeding, Smith flashes a wry smile.

“Uh, no,” he laughs, “not right now. But um, I think I … but I think I might, you know.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

As he wagers thus, Smith starts and shifts, tilting his head in pained deliberation. For a rather brutal question that can only really be laughed off, Smith’s response is as naked and honest as his best lyrics.

Come October, legions of Smith-loyals will mourn the 20th anniversary of his passing. The circumstances of that infamous death — suicide or perhaps murder — threaten to distract from Smith’s rich musical legacy.

Charm, nonchalance, intelligence, mischief — all come across in the above interview clip. Smith cuts a cool figure, clearly burdened with some ineffable pain, but quick to downplay it. Above all, one gets a thin slice of a beautiful soul, as many-shaded as they come, strikingly witty and unmistakably bright.

Peruse Smith’s catalog and you may come away with a different descriptor: sad. When I first heard him, I was almost uncomfortable with how closely I thought his voice matched the emo archetype. But to write him off under that or any other label is to do him the same disservice done to far too many “sad singers”: to conflate broad-spectrum emotion with sadness alone, self-expression with whining.

Elliott Smith’s artistry lies in the bareness of his lyrics and piercing insights. His subject matter is usually dark: lost love, oblivion and, frequently, addiction. These themes were conduits for expression of universal elements of the human condition, from dependency to loneliness.

If one were to try to quantify Smith’s music, the epitaph “genius of expression and underrated guitarist who shaped a generation of songwriting” might do. He’s often called “Mr. Misery,” a reference to his Oscar-nominated song “Miss Misery” featured in Good Will Hunting, but that nickname’s a little heavy on, you know, the sadness.

Every one of his songs rings with raw feelings. Some lines strike abruptly, as on “Twilight” which opens with, “Haven’t laughed this hard in a long time/ I better stop now before I start crying.”

Others stop you in your tracks once they’ve sunk in. See “Better Be Quiet Now,” where Smith sings, “Had a dream as an army man with an order just to march in my place/ While a dead enemy screams in my face.”

Smith delivered line after line of this sort, only later clothing his dry humor in layered instrumentation. He faced darkness head-on and reported back gently, if bluntly.

Listeners today may struggle to grasp how revolutionary Smith’s sound was. Emerging from the dense forest of ’90s grunge, he sat alone with a guitar, delivering lyrical blows in a deafened hush. That today the solo acoustic singer-songwriter is anything but rare is a testament to his vast influence.

Phoebe Bridgers has joked that not liking Smith’s music is a dealbreaker in friendship. Lucy Dacus quipped, “Everyone I know that makes music is ripping this guy off.” As for Smith, he called the Beatles and AC/DC his biggest inspirations.

Smith’s Beatles streak runs strong. Either/Or is rightfully regarded as his masterpiece and is home to three of the five tracks of his featured in Good Will Hunting. His arresting self-titled record is quintessential Elliott, dark and bare, often only guitar and doubled vocals. But it isn’t until 1998’s XO and 2000’s Figure 8 — my personal favorite — that he harnesses melody and color like Lennon and McCartney.

These last two records solidified his place as the most deserving heir to the Fab Four’s legacy — and yet even this feels too confining for Smith. He spans the breadth of human experience in his music, feeling everything, bringing the listener from the brink of mournful resignation on songs like “The Biggest Lie” to the surging, defiant resolve of “Can’t Make a Sound.” The rolling “Waltz #2” is near perfect.

I remember reading the words of one of Smith’s friends while knee-deep in his discography for the first time. He said that nowadays, he rarely listens to Elliott’s stuff because he doesn’t like the place it takes him. I thought this was insane.

Now, a few months removed from obsessive immersion, I understand completely. Elliott brings you face-to-face with aspects of yourself and the world you often don’t want to acknowledge, things that make you wince.

Far from a sign of weakness, his sensitivity to painful truths and his willingness to convey them so clearly marked his strength and courage. These are the qualities we should remember him by.

Eddie is a senior in LAS.