Robobrawl: the University’s largest robot showdown

April 26, 2018

A crowd of well over a hundred people surround a large acrylic cube near Grainger Engineering Library, with children taking the front seats to see the spectacle to occur inside. The incessant chatter quiets down as the announcer’s voice pierces through the air. At the count of “Fight, robots, fight!” the battlebots clash, and the fourth annual Robobrawl begins.

Organized by student RSO iRobotics, Robobrawl is a yearly competition held during Engineering Open House that gives students the opportunity to construct fighting robots and entertain crowds.

The competition, spanning March 9-10, saw its largest turnout yet with 16 robots participating in the double-elimination bracket. Teams were comprised of University students, iRobotics alumni, and — for the first time — outside universities as students across Illinois, North Dakota and even Canada traveled to Urbana-Champaign to compete.

The Battlebots

To enter Robobrawl, each team must create a robot from scratch. Each battlebot must be under 30 pounds, have the ability to move around the arena and wield some sort of weapon.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

These broad rules allow for flexibility in bot design, but there are some common templates for battlebots. A common weapon choice is a spinning saw or blade designed to tear the opponent apart, used in bots known as “vertical spinners” or “horizontal spinners” depending on saw orientation.

Another popular style are “wedgebots,” which use a bulldozer-style arm to flip opponents on their backs or out of the arena.

According to Nick Jew, senior in Engineering and person in charge of livestreaming Robobrawl, there is a lot more nuance and skill that goes into bot design than spectators might notice. “It’s gotta be balanced,” Jew explained. “There’s a lot of engineering design in figuring out what’s the best way to have a weapon that’s structurally sound but also has a pointed end so it can actually hit the opponent.”

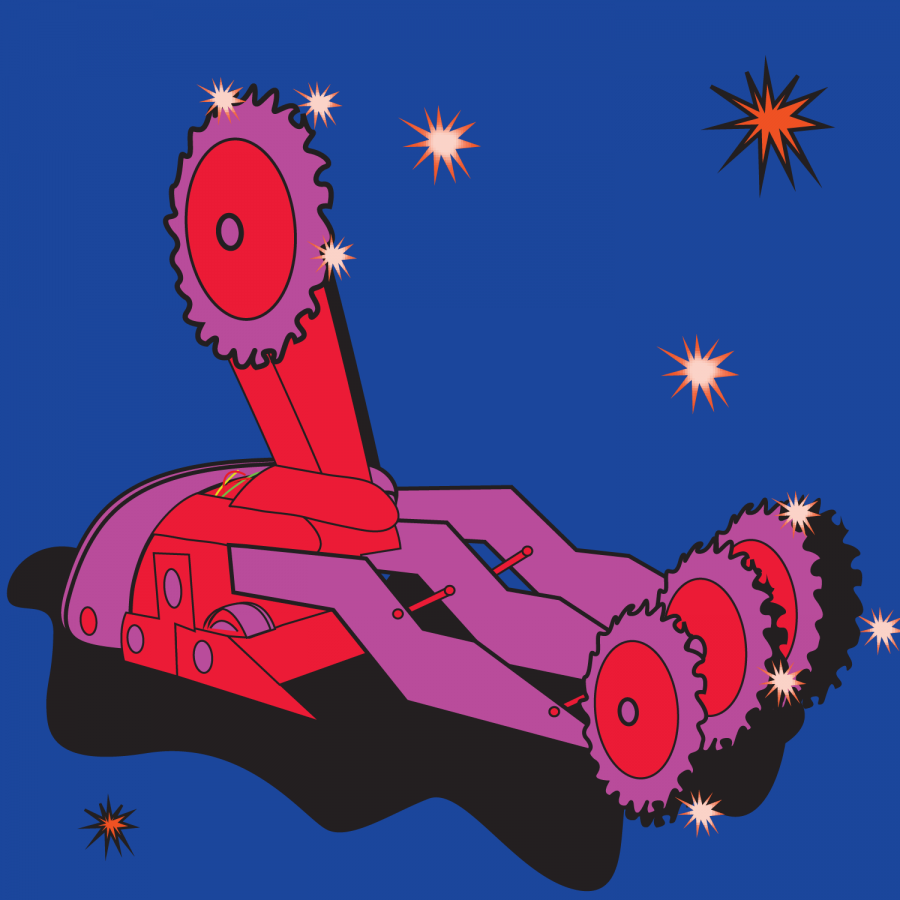

Michael Kokkines, freshman in Engineering and captain of the iRobotics freshman team, led the building and designing of the horizontal spinner, “Space Jam.’”

“We used a horizontal bar that spins really fast,” Kokkines said. “And around that, we built a square frame with the bar in the front.”

The wiring and wheels were positioned in the back of the bot, protected by a steel frame to minimize damage.

Meanwhile, Robobrawl coordinator, junior team captain and junior in Engineering Tor Shepherd kept busy with his two positions. When not overseeing the management and execution of the competition, Shepherd helped the juniors construct “Botman,” a vertical spinner with a large serrated wheel mounted on an armored base.

With bots geared up and ready to fight, the competitors were brought to tents around the arena, a square metal stage with sides 15-feet long and the word “Robobrawl” inscribed in bright orange and blue paint.

The aim of each one-on-one battle was to immobilize the opposing bot. Some matches ended in battlebots flailing on their backs, while others created explosions of metal parts scattering around the protective walls and ceiling.

Between matches, teams had to quickly repair the damage their bots sustained, and even winners had to be concerned about their preparedness for the upcoming match.

“Even if you win your fight, you could still be so badly damaged that you cannot compete in your next battle,” Shepherd said. “Some people get away with just one wire getting unplugged and some people have their entire robot in shreds.”

Shepherd and the junior team ran into technical problems during the competition, as loose wiring in “Botman” led to losses in both of its matches.

Meanwhile, Kokkines’ “Space Jam” took an early loss to the senior team, but it managed to pull off one win in the loser’s bracket before falling to the bot that would win the entire tournament: “Wall-F.” Built by an iRobotics alumnus, the agile wedgebot employed its winning strategy of flipping opponents before pinning them against the arena wall on their side, preventing all movement.

But during a filler match, “Space Jam” scored its — arguably — most important victory against a foe notorious in the iRobotics circle: a simple, unpowered fan.

Last year, the home appliance was set up to be destroyed by previously eliminated battlebots between tournament matches for entertainment, but an unexpected problem soon came up.

“For some reason, no bot could actually destroy it,” Jew said. “So we declared it the unofficial winner of everything last year.”

After inexplicably pinning and defeating an unfortunate competitor this year, the fan’s reign finally came to an end when the freshman team obliterated it into plastic shards, to the joy of the onlooking audience.

“People have had some trouble dealing with the fan, but we were able to destroy it,” Kokkines said.

Despite not winning their own tournament, University students involved in Robobrawl enjoyed the experience the competition had to offer. Kokkines praised the close relationships he formed with teammates and alumni, while Jew said the “intense battles” and hands-on excitement could inspire children to develop an interest in engineering.

As for the tournament itself, Robobrawl will be doubling its number of entries to 32 battlebots next year, with more outside universities expected to participate. Shepherd encourages more students to get involved with the growing event.

“We’re always looking for more people to help out with the competition or the robots,” Shepherd said. “They can just join iRobotics, and as soon as the semester starts, you can get right into it and start building robots.”