Will Krug finds time for baseball, life with the help from those closest

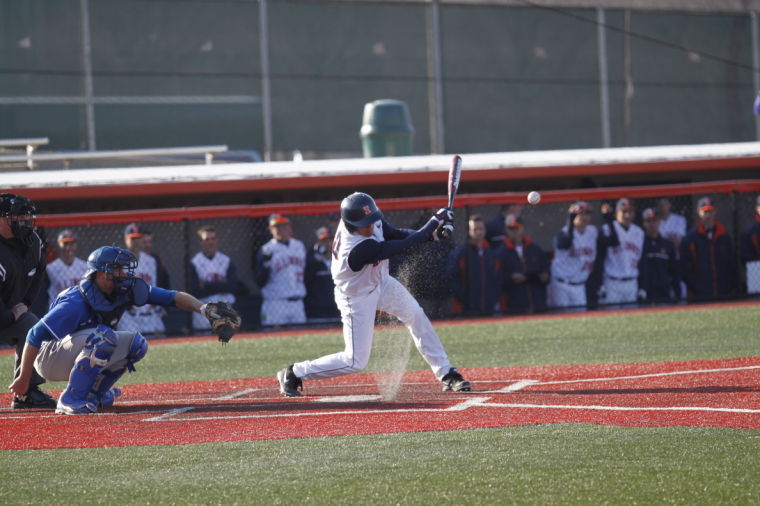

Illinois’ Will Krug (40) hits the ball during the game against Indiana State at Illinois Field on Tuesday, Mar. 18, 2014. The Illini won 8-0.

May 8, 2014

Will Krug sinks back into the couch cushions in his apartment late Monday night and thinks about the most challenging part of his life.

He pauses for a moment before answering, considering everything he faces on a typical day. The questions people ask him about his life usually come with simple answers.

As the leadoff hitter and starting center fielder on the Illinois baseball team, he gets ambushed with the same set of questions from a flock of reporters before and after every game.

He doesn’t mind, though, especially considering he wasn’t medically cleared to play a year ago. All year he has answered each question with a cool, collected response:

How’s the offense? Strong. How’s the defense? Stronger. What can you guys do to prepare for the next game? Keep working hard and playing our game.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

And when they learn he studies civil engineering with a minor in bioengineering, the questions change to another predictable set, which he answers no differently:

Wow, how tough is it to balance baseball and your course load? Very. How do you do it? I don’t know, but I find a way. Why do you do it? Because I love it.

Today is the team’s off day, which doesn’t mean he can take it easy. Most of his day consists of busy work to prepare for his upcoming final exams. And on these days, the questions are light to nonexistent — except for that today. And so he thinks about how to best answer.

“I … don’t know,” he says, still thinking about the most challenging part of his life.

Then, it hits him.

“Time,” he says with a sigh. “There’s just not enough to do everything you want to do.”

“You need help from people.”

Showing up

Associate head coach Eric Snider still remembers the first time he saw Krug, entering through the front gates of Illinois Field for walk-on tryouts in 2011.

Snider stood just beyond a fence somewhere deep down the left field line. He was setting up the 60-yard dash to test newcomers on their speed. From that vantage, he and the other coaches can always tell which guys arrive unfocused or hungover from the night before by the way they amble about.

Krug didn’t amble. Instead, he brought enough energy for Snider to notice the 5-foot-8 freshman before he finished filling out the paperwork.

The tryouts consisted of the 60-yard dash, throws from the outfield and a live scrimmage that pitted batters against pitchers to simulate a normal, in-game scenario. One of the pitchers Krug faced was Anthony Milazzo, now one of his current teammates.

“Everything that he did, he sprinted up where everybody else walked up,” Snider said. “And at the end of the day, he picked up all the helmets.”

At the time, Snider couldn’t have known what Krug had done leading up to the tryouts.

His choice to come to Illinois was solely based on education. Several Division II and Division III schools had recruited him out of high school, and even one Division I school in upstate New York. But none were Illinois.

“And I knew I wanted the civil engineering education from the U of I,” Krug said.

The plan then became to walk on to the team, with club baseball as a less preferred alternative.

When Krug arrived on campus, two weeks stood between him and the tryout date, a time he felt he couldn’t let go to waste by doing nothing.

For liability issues, he wasn’t allowed to practice at any of the team’s facilities, which led to The Cage in downtown Champaign just off I-57 — about four miles from his dorm room. He traveled there almost every day leading up to the tryouts. Sometimes, the bus took him most of the way. Other times, he walked.

“Walked!” said his mother, Lori, still in disbelief two years later.

If walking to The Cage gave him the best chance, Krug didn’t mind. And his parents didn’t mind helping him afford it if it meant maintaining the cornerstone of his passion.

Slowing down

Other coaches didn’t believe the Illinois staff when it said it took a walk-on outfielder. Usually, teams let pitchers and catchers walk on. Not every tryout brought players who could run the 60 in 6.8 seconds. Or who could throw balls from the outfield at around 90 mph.

Krug knew how to use his speed as a small player, which was part of the draw for head coach Dan Hartleb.

Ask either Krug or his father where he gets it, and both will point directly to his mother. To this day, Dewi — as she prefers to be called — holds a spot in the hall of fame at Ripon College in Wisconsin. Her fifth-place national finish in the 1,500 meter run in 1981 helped make her Ripon College’s first female All-American.

That inherited speed earned him 15 starts his freshman year, 11 as designated hitter and four in right field. It also gave him enough confidence to steal bases against unfamiliar speeds of collegiate pitchers.

Two years later, Krug leads the Illini in stolen bases and steal attempts with 18-for-25 as a junior this season.

But through his freshman year and into his sophomore season, Krug began relying on his speed almost as much off the field — more specifically, on the way to it.

While careful class scheduling alleviated some of the stress, Krug found that his classes often ran right up until practice. The narrow window gave him just enough time to grab a peanut butter and jelly before he had to rush to batting practice — and sometimes not enough when professors held their classes behind to discuss material.

“I know he gets frustrated not being able to put in all the time needed for his major,” his mom said. “You can’t hurry engineering.”

Krug confessed to breaking into a run sometimes on his way to practice, with Snider always there to joke about his commitment. Jokes, and nothing more, because once Krug arrives at the field, everything switches over to baseball.

“Mentally, he gets too fast,” said his father, Arthur. “That’s when you see Coach Snider slow him down.”

Krug’s work ethic wound up an issue in the most untraditional of ways. The same effort he brought on the first day didn’t seem to have much of an off switch, at least not one he could regularly flip.

Whenever he gets too wound up or harps on a bad at-bat, Snider steps in to unwind him and keep him from carrying one bad moment with him.

“For Will, it’s about not thinking that he’s going to go 20-for-20,” Snider said. “When I see him speeding everything up, I have to remind him to slow it down.”

Getting back up

At the beginning of his sophomore year, other forces intervened to help Krug step on the brakes.

Athletic trainer Jim Halpin noticed he was showing symptoms of an athletic pubalgia — or a sports hernia, as it’s commonly called. Fortunately for Krug, the injury was something that could be worked through without missing playing time. A few anti-inflammatories and steady rehab exercises should have been all it took.

And it might have been, too, had a full-count fastball not smashed against his left arm at Indiana on April 5, 2013.

Krug didn’t think the pitch would hit him up until the moment it did. And even once it had, he couldn’t have guessed it had broken his arm.

If he’d known, there’s a chance he wouldn’t have stolen second base on the next few pitches — but probably not a big chance. The Illini were down two runs in the eighth inning.

“I ended up scoring and stayed in the game,” Krug said. “I was about to go on deck at the end of the game, but I don’t think I’d have been able to swing the bat if I tried.”

Both of his parents were up in the bleachers that night and could immediately tell something was wrong by the way their son held his arm, tenderly and displaced.

The next morning, when Krug couldn’t even turn his arm over, Indiana opened up its x-ray facilities to examine the injury. The verdict was a cracked ulna bone in his arm, which left the rest of his season unclear.

“With a broken bone, you’re never quite sure how fast it’s going to heal,” Halpin said.

The original hope was he’d be out four to six weeks, with an x-ray every other week to monitor the healing process. Because of the broken bone, he was taken off the anti-inflammatories, which meant he would need surgery to correct his sports hernia. And when the bone showed no immediate signs of healing, the Illini coaches were forced to make a decision.

“Just let the bone heal, go do the surgery, and then we’ll regroup and start over again in the fall,” Halpin said.

Krug spent two months on the sidelines, watching his team succeed without him in the leadoff spot. He was around for the three remaining home series, but the NCAA travel rules didn’t allow him to travel.

When the team played in the NCAA regional in Nashville on May 31, Krug watched from a TV screen, his attitude positive the entire time. And why not? His thoughts and efforts on the baseball field are always toward the betterment of his team.

But no amount of effort or energy changed the fact that there was nothing he could to help his team. In Illinois baseball’s most important moment since he arrived, he was completely helpless.

“To get injured like that, I’m sure it was crushing,” Snider said.

If anything, though, Krug’s helplessness added more perspective to his situation. He never appreciated the words “slow down” more than when he was at a dead halt.

He thought about how fast he had been moving before his injury, and how much faster an injury can take it all away. Every game, every at-bat, every moment had been taken for granted before, and he would never let that happen again.

“It could end tomorrow,” Krug said. “School work, or anything now, I give it 100 percent of my effort now.”

Holding it together

When Krug came back in the fall, he still worked as hard as he had on his first day.

“He was still trying to make up six to seven months all in one day,” Snider said. “And it’s not going to come back in one day.”

Time off in the summer gave him a chance to understand just what it took to make a life like his work.

Doing things fast didn’t mean constantly worrying about letting things slip by. It meant accepting he could only do so many things with his time.

“There are only a limited number of hours in the day,” Krug said.

It also meant he had to accept those things could only be done with the help from others, whether its getting reads from pitchers or having a teammate quiz him for tomorrow’s biology quiz.

When he and teammate Andrew Mamlic pull books out from their carry-on bags, they don’t mind other players tease them about it. Even if the plane ride is only about 45 minutes long, it’s time free to get one extra homework problem done.

“He’s woken me up to ask me questions,” Mamlic laughed. “But you’ve got to manage your time somehow.”

If running into practice from his parking spot in the dirt lot gives him an extra minute to practice baseball, Krug will take it.

“I’ll work as hard as I can and play as long as I can,” Krug said. “That’s kind of a dream right now, and I’m just going to keep chasing it.”

In games, he still uses his speed to steal a base whenever he gets the chance, but he’s not as anxious about getting there as he once was. He knows he can count on help from his teammates to put their team in a position to win games.

And when the games are over and the media crowd finally fans out, he always makes sure to carve some time to visit his family down on the field.

Because when there’s enough time for the things in life you love, it takes a while for the challenges hit you.

J.J. can be reached at [email protected] and @Wilsonable07.