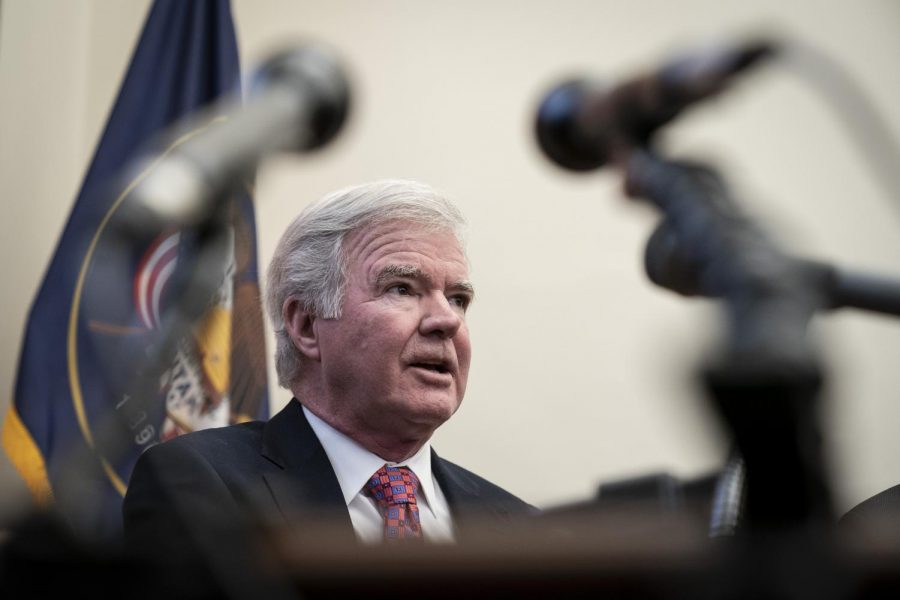

NCAA President Mark Emmert testifies on Capitol Hill, asks Congress to do his job

Photo Courtesy of Drew Angerer/Getty Images/TNS

NCAA President Mark Emmert speaks out against anti-transgender legislation at a brief press availability on Capitol Hill on Dec 17, 2019. Recently, Emmert testified in Congress about name, image and likeness rights for student athletes.

June 10, 2021

NCAA President Mark Emmert appeared before the U.S. Senate Wednesday to testify about name, image and likeness as state legislatures across the nation move to pass NIL legislation.

But what is NIL, and how did we get here?

In 2019, California passed legislation to allow athletes to be compensated for name, image and likeness. In non-legalese terms, athletes at NCAA schools in California would be able to receive compensation from endorsement deals or through marketing, similar to how professional athletes do.

The NCAA and some member schools, including Stanford, vociferously opposed the legislation at the time. California’s law is set to take effect in 2023, but the landscape of name, image and likeness has changed significantly over the last year and a half.

Other states have followed California’s lead with similar name, image and likeness laws, many of which are set to take effect next month. The states will have different laws on the books at that point, and the NCAA is quite worried about discrepancies between laws in states once NIL legislation goes into effect. Now they’re asking Congress to step in, and Wednesday’s hearing addressed actions Congress could take.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The Senate hearing comes as lawmakers are trying to pass federal legislation before the states’ laws take effect July 1. Of course, Emmert acted like these issues are too complicated for his organization to solve.

But the senators weren’t having it.

To be fair, it’s not like Congress was trying that hard to ask the biggest stakeholders — the athletes themselves — how they felt. Out of the panelists at the hearing — Emmert, Gonzaga men’s basketball head coach Mark Few, ESPN football analyst Rod Gilmore, Howard University President Dr. Wayne Frederick, University of New Hampshire law professor Michael McCann and Marquette University law professor Matthew Mitten — none of them are current student athletes. Gilmore played football and baseball while an undergraduate at Stanford.

Oh, and as is somehow par for the course for the NCAA, none of the panelists were women. Gilmore said the NIL legislation was likely to benefit women athletes, but the only women who spoke during the hearing were U.S. senators.

Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Washington and chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, briefly mentioned some of the issues that athletes have raised awareness about, including Oregon women’s basketball player Sedona Prince’s TikTok video detailing the unequal treatment at the respective men’s and women’s NCAA basketball tournaments in March. Cantwell said at the end of the hearing that the Senate would have a student panel, but as of publication, nothing is on the Senate Commerce Commitee website about this.

As divided as Washington is, the senators were collectively critical of Emmert and why they have to do his job for him.

Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, questioned why the NCAA was considering an antitrust exemption — meaning that if the NCAA has the exemption, under NIL legislation, the NCAA would be immune from NIL-related lawsuits. Emmert denied seeking antitrust protection.

“I don’t know who has advocated on behalf of a total antitrust exemption,” Emmert said. “Quite the contrary. I think that the issue at hand is simply around the application of this particular NIL rule. And that the need is for the avoidance of serial litigation either for previous actions or future actions in the application of the NIL law.”

Emmert worried his inaction on NIL would result in a lawsuit once his organization abides by NIL laws, telling Senators bluntly: “We’re trying to avoid moving toward a place where no good deed goes unpunished here.”

The NCAA has been found to violate antitrust laws before. In a 1984 Supreme Court case, the NCAA TV deals were found to violate antitrust law. The U.S. Supreme Court is currently reviewing NCAA v. Alston, which looks into whether the NCAA violated antitrust law.

Congress has proposed a number of bills to work on name, image and likeness. Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Mississippi, and Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Connecticut, have both proposed legislation about name, image and likeness. Wicker’s legislation is more favorable to the NCAA, including some liability immunity, while Blumenthal and Sen. Cory Booker, D-New Jersey, have been in favor of and introduced a NCAA player’s Bill of Rights, which would require NCAA schools to publicly report revenues and expenditures and share 50% of after-scholarship revenue with players.

Both items of legislation were introduced in late 2020, and the Senate has since flipped. After the Georgia runoff elections in January, both parties have 50 Senators, but Democrats gained control of the chamber, as Vice President Kamala Harris, a Democrat, is the tie-breaking vote.

Blumenthal stated he will block any bill that is more restrictive than the bill his home state of Connecticut passed Wednesday. Student-athletes at Connecticut universities will be able to earn money from endorsements or employment relating to name, image and likeness, as well as hire sports attorneys beginning Sept. 1.

Wicker’s legislation, introduced in December, narrowly focuses on name, image and likeness, but it also provides some clauses favorable to the NCAA, including that student-athletes are not considered employees. In 2015, the Northwestern football team’s attempt to unionize failed after the National Labor Relations Board said the players were primarily students and not employees.

Wicker’s legislation is also silent on whether students could hire sports attorneys (searching the bill for “lawyer” and “attorney” returned no results), but it does mandate career counseling for students on NIL.

Back in Washington, Congress wasted no time Wednesday grilling Emmert and his organization for their misdeeds.

Booker testified at the hearing Wednesday morning — he does not sit on the Commerce committee. Booker, who played football at Stanford, pointed out how exploitative modern college sports are.

“Modern college athletics, is, de facto, a for-profit industry exploiting men and women, taking advantage of their genius, of their talent, of their artistry, robbing many of them of earnings in their peak years, leaving them often injured with a lifetime worth of costs,” Booker said in his opening statement.

“But there are deeper issues we should talk about as well that have not been fixed. Since 2000 alone, we’ve seen the death of at least 30 players who have died from heat-related illnesses. We now have a better understanding of what concussions do to athletes throughout their lives. But we are sitting here at a time the NCAA doesn’t even have an enforceable concussion protocol.”

While answering a question from Sen. Jon Tester, D-Montana, about how health protocols are enforced in the NCAA, Emmert said the NCAA does not directly enforce health protocols.

“There is not an enforcement system in place at the national level,” Emmert said. “Every university is expected to follow all the health and welfare protocols that are in place, and when they fail to do so, it’s usually dealt with at the institutional level and at the state level.”

Emmert’s organization’s failure to enforce health protocols wasn’t the only thing lawmakers took issue with.

Blumenthal slammed Emmert for wanting federal lawmakers to act in place of the NCAA while his organization does not protect student-athletes. He argued the NCAA does not want the states to legislate NIL and is now asking Congress to step in.

“The overwhelming number of athletes in this country will never make a lot of money off NIL, but all too many of them will suffer life-changing injuries or deprivation of educational opportunity and other kinds of harm we’re seeking to protect against,” Blumenthal said. “Let’s be very real here. The NCAA is at the table only because they were hauled kicking and screaming after waiting too long, and they’re here only because they fear that patchwork.”

Emmert has, in recent years, seemed to pivot his opinion on NIL. In 2019, he criticized California lawmakers who passed NIL legislation and called NIL, according to CBS Sports, an “existential threat.” Emmert indicated support for NIL during Wednesday’s hearing.

After the hearing concluded Wednesday, the Pac-12, Big 12, Big Ten, ACC and SEC — which signed the press release as the “Autonomy Five Conferences” — sent out a press release:

“The Autonomy Five Conferences thank Chair Maria Cantwell and Ranking Member Roger Wicker for today’s hearing and their determination to set a fair and enforceable national standard on NIL. Only Congress can pass a national solution for student-athlete NIL rights. The patchwork of state laws that begins on July 1 will disadvantage student-athletes in some states and create an unworkable system for others. As leaders in college athletics, we support extending NIL rights in a way that supports the educational opportunities of all student-athletes, including collegians in Olympic sports who comprised 80% of Team USA at the Rio games. We continue to work with Congress to develop a solution for NIL and expand opportunities.”

While the conferences asked the solution to come from Congress, the senators didn’t seem to think it was inevitable that Congress would have to act. Sen. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tennessee, and Blumenthal both chastised the NCAA for its inaction on the issue, which forced Congress’ hand.

“We thought the NCAA was going to be able to step forward and set the rules,” Blackburn said. “The inability of an organization that makes a tremendous amount of money whose leadership (is) paid a tremendous amount of money, and it is all coming from these student-athlete events, but yet, the inability to move to a point of decision has just been an insufferable, insufferable event for so many of these student-athletes and their parents. This is why the states have taken it upon themselves to do what the NCAA has proven incapable of doing.”

Toward the end of the hearing, Sen. Ben Ray Luján, D-New Mexico, asked all the panelists, including Emmert, if they believed athletes should be able to earn money from name, image and likeness deals. All said yes, to which Luján replied:

“Given that, why did it take so long?” Luján asked. “We’ve been having this argument for over a decade, coaches are making millions of dollars while students make nothing. Dr. (Emmert), can you answer that?”

Emmert’s lackluster leadership came into question, and Blackburn began her questions asking Emmert if he has the capacity to continue to lead the NCAA.

“My question to you is simply this: Do you think it is time to call your leadership of the organization into question?” Blackburn asked. “Do you think you are still capable and fit to lead this organization to make a decision that is going to be fair to the student-athletes and their parents?”

In typical Emmert fashion, he sidestepped Blackburn’s question.

“Senator Blackburn, with all due respect, that’s not a question that I need to answer,” Emmert said. “That’s a question that those for whom I work need to answer.”

@obrien_clairee