Generation of gymnastics

February 6, 2007

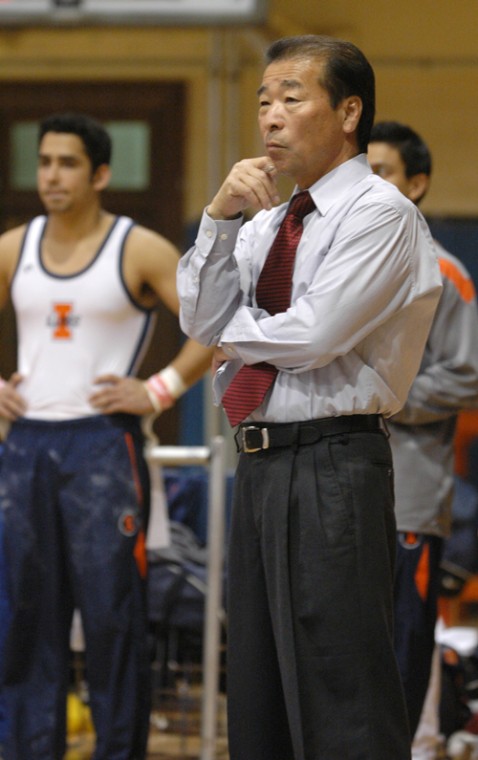

When Yoshi Hayasaki was first offered the Illinois men’s gymnastics head coaching position in 1974, he never envisioned staying more than a few short years.

The walls of his H.E. Kenney Gymnasium office tell an entirely different tale.

Photos of the 75 All-Americans Hayasaki has coached are prominently displayed, leaving the only recognizable proof of the talented athletes that once graced the University. The mounted frames, as well as the trophies that adorn his Bielfeldt Athletic Administration office, are indicative of his decision to forgo a short-term coaching position for one of permanence and permeating perfection.

Only 26 years old when he took over for the retiring Charlie Pond, Hayasaki didn’t know the first thing about molding young gymnasts. At that time, Hayasaki was still a student of the sport – competing for AAU national championships. Hayasaki, a two-time all-around NCAA national champion, a four-time AAU national champion, a United States Gymnastics Federation champion and the winner of 20 individual event titles in his career, lacked a driving factor necessary to be a good coach.

As impeccable as his credentials were, Hayasaki didn’t know the first thing about recruiting. Hayasaki tried to be a coach and compete at the same time for his first six seasons, but it wasn’t easy and it took a toll on him, he said. Any athlete who wanted to come to Illinois and become a part of the gymnastics team was welcome, he said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Things changed quickly after Hayasaki adjusted his attitude and started taking cues from the most successful coaches in the Big Ten conference.

“I guess I started getting tired of losing or of not winning,” Hayasaki said. “All the coaches knew the ins-and-outs of recruiting, and I was very new at this. I just got tired of that.”

“You can only do so much with coaching, but you have to have talent; you have to have the horses,” he added. “You can get up to a certain level of competitiveness, but to win the championships you have to have a little bit of talent to begin with.”

Winning ways

More than 25 years later, Hayasaki is still the driving force behind recruiting some of the nation’s top talent. Now in his 31st season as head coach, Hayasaki’s competitive nature and desire to build and develop championship-caliber teams has not wavered, he said. He feels his days are just as interesting as they were in 1974, and it’s his love of the sport and wanting to watch over gymnasts’ progress that keeps him inside Kenney Gym each afternoon.

But Hayasaki said that when he does retire, he hopes his future endeavors are as enjoyable as coaching the Illini. In four years, Hayasaki will evaluate his future with the program, but only after determining what is best for his family – his wife, Lisa; and his children: Erika, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times; Casey, a former Illinois gymnastics team captain; Megan; and Mia. His goal in the meantime is to win another NCAA national championship.

“We were coming so close to winning a national championship and then (last season) fell short by a very small margin – it keeps me going,” Hayasaki said, referring to the Illini’s loss to No. 1 Oklahoma by .425 of a point at the NCAA championships. “The taste of that national championship is great; you’re talking about (being the) best team in the country. That’s what you strive for as an NCAA coach.”

Hayasaki’s first national championship came in 1989 – the first NCAA championship in any sport at Illinois in more than 30 years. His first Big Ten Championship came in 1981, followed by conference wins in 1983, 1988, 1989 and 2004. Big Ten Coach of the Year honors surfaced in 1988, 1989 and 2004, along with National Coach of the Year recognition in 1989.

A native of Osaka, Japan, Hayasaki has coached 75 All-Americans, 39 individual Big Ten champions, nine national champions and two Olympians, and began the 2006 season with a 268-145-2 (.649) overall record in 30 seasons at Illinois.

Hayasaki attributes his winning record to a number of things, among them his organization. Following each week’s meet, Hayasaki, who at practice is never without his clipboard full of recent scores and each gymnast’s tracked progress, holds team meetings to critique the trials and tribulations he has witnessed. His adjoining office is also always open for Illini to talk with him, as well.

“I have a plan from A to B or F or whatever stages they have to go through,” Hayasaki said of structuring the team’s workout schedules. “I plan the whole year’s schedule. If we are able to follow that step-by-step approach we are going to be able to get to where we want to get.”

Above organization, though, Hayasaki said that the environment in which athletes train is important in developing Big Ten and national champions.

“I also like to create a place where they feel comfortable and excited about their training,” Hayasaki said of his gymnasts. “Because I want them to be productive, getting the most out of their training. After all, that is what coaches have to do, is to maximize their potential.”

Every afternoon at 3 p.m. when the Illinois gymnasts enter the second-floor training area, comprised of state-of-the-art pommel horses, still rings, parallel bars, high bars, vaulting horses, spring floor and 40-foot-long tumble track, they enact a 30-year-long tradition. As a step toward maximizing potential, the Illini bow as they step into the gym, a ritual that expresses their commitment to put 100 percent effort into each workout.

Back to basics

As a veteran coach, Hayasaki also puts emphasis on fundamentals. Knowing the benefits of early training, he requires his teams to be competition-ready as soon as possible, said junior co-captain Wesley Haagensen.

“He likes to take things and perfect them to the best, regardless of what it is,” Haagensen said. “He’s always telling you to have your toes pointed, or you need to open your hips a little more, regardless of what skill it is. It just shows he likes everything to be better – be perfect.”

Perfection is something Hayasaki learned early on in his life.

Drawn to gymnastics at a young age, Hayasaki was one of the top five gymnasts in Japan when he competed at Tenri High School – a school with a rich gymnastics program. Hayasaki could have stayed in Japan and competed on the Olympic team, but instead chose to attend the University of Washington-Seattle and earn a college degree. The pull of being recruited to compete at Washington was stronger than remaining in his native country.

“I had a chance to leave Japan and get a good education and still do gymnastics, although I wasn’t sure what the future might hold in terms of gymnastics,” Hayasaki said. “But I promised my parents when I left that I will graduate from college, and some day I am going to be a champion in America.”

Making good on both promises, Hayasaki, in 1971, earned bachelors of arts and science from Washington, where he was a two-time all-around national champion, and also received a master of science in teaching from Illinois in 1973.

Although Hayasaki’s brother and sister still live in Japan, he doesn’t regret his decision to come to the U.S. His only regret was never making an Olympic team, he said.

Hayasaki came close, but a string of difficult events transpired. In 1968, Hayasaki was crowned the all-around champion at the USA Championships, and without U.S. citizenship, he asked the Olympic committee if he could compete with Japan in the Olympic trials. The committee held four tryouts, but as a student, Hayasaki couldn’t take that much time off school. The committee denied his request.

Still determining his options, Hayasaki tried to make the team in the U.S. He applied to become a U.S. citizen, but two weeks after applying, he was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War.

“Then luckily or unluckily, I tore my Achilles tendon that (same) week – the week before the physical exam to be sent overseas,” Hayasaki said. “I had a cast on. I escaped from going to the Vietnam War, but at the same time lost the chance to compete in the Olympics.”

Although Hayasaki said he never entertained thoughts of coaching at another university, he needed to take time off from the rigors of being a head coach. From 1993-1996, Hayasaki served as Illinois’s director of gymnastics for the men’s and women’s teams.

“I was burning out a little bit; I’d coached for 20 years,” Hayasaki said. “We won the national championship, we did a lot of things, and I kept pushing until my mental exhaustion took over.

“And maybe I’m not as knowledgeable as today at that time, but I was going 110 percent.”

The timing of the break was just what he needed, he said.

“That opportunity really refreshed and rejuvenated me to come back to coaching,” said Hayasaki. “Since then it’s been almost 10 years. It’s lasted this long, and I still feel very refreshed.”

Without the break, Hayasaki would not have lasted as long, he said. But in testing the limits of time, it has caused a number of fellow Big Ten coaches to take notice, among them Ohio State head coach Miles Avery, who is now in his 10th season with the program and has led the Buckeyes to an NCAA national championship and four Big Ten titles. He credits Hayasaki for “sparking” many of the “double duel” meets that are now customary in the Big Ten. In addition to looking up to Hayasaki, Avery said he can only have “respect for anyone who does a job for 30 years and does it well.”

“When we come here, we don’t know what’s going to happen because we know they are going to put a good team out on the floor, and everyone else in the Big Ten looks at that,” Avery said. “When you go to Illinois, you know you are going to be in for a fight.”

Facing the future

This year’s team includes four freshmen and no seniors, and it is one of Hayasaki’s toughest assignments yet. Because of Hayasaki’s competitive nature and motivating personality, freshman Luke Stannard thinks the coach will be up to the challenge.

“I think that he gets down on a personal level, and you can really relate to him,” said Stannard, whose coach at Warren Township High School in suburban Chicago competed for Hayasaki when he was at Illinois. “He’ll always reiterate things until you know exactly what you’re doing wrong, and that’s really helpful.”

Because Hayasaki knows what it takes to win championships as a coach and as a gymnast, Stannard said it’s easier for Hayasaki to know what young gymnasts go through in their first few seasons.

“He’s aware it’s a very large adjustment from where we were coming from,” Stannard said. “He pushes us, but he knows that we need time to get to that level (of where recruits are expected to go.)

“It helps that he’s done these tricks before.”

While Illinois’ chances of winning a national championship are slim this season, it has realistic chances in the next few years. Although Hayasaki is soft-spoken, stands just five-foot-four, and has accumulated more wrinkles with each passing season, he is just as competitive as when he won his all-around national championship in 1968.

“When you have competitive teams and have a chance to win a national championship, it’s fun,” Hayasaki said. “All the positive things override the negative and it becomes a fun ride.”