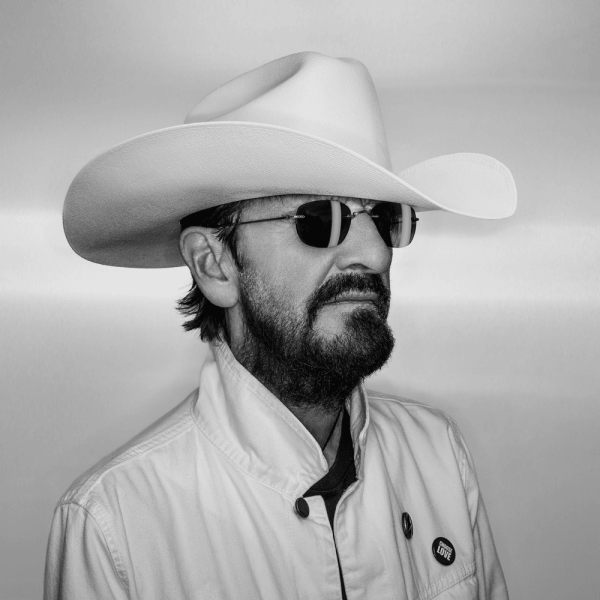

The evolution of Rayvonte Rice: Proving he belongs in Big Ten

Illinois’ Rayvonte Rice takes a free-throw during the first round game of the Big Ten Men’s Basketball Tournament against Indiana, at Banker’s Life Fieldhouse on March 13. The Illini won 64-54.

April 1, 2014

Four years ago, Rayvonte Rice wasn’t good enough to play in the Big Ten.

Bruce Weber didn’t think so. Tom Izzo didn’t think so. Bo Ryan didn’t think so. Not one of the 11 Big Ten coaches offered Rice a scholarship.

He was a star at Centennial High School in Champaign. He and Ohio commit James Kinney led the school to a 3A state championship his junior year, with Rice averaging 16.8 points and 7.0 rebounds per game. Without Kinney his senior year, Rice took on an even larger role, leading the Chargers to a fourth-place finish, averaging 23.9 points and 6.4 rebounds per game. He was a unanimous first-team all-state selection. He was the runner-up for Mr. Basketball behind Jereme Richmond, Illinois’ small forward of the future.

But it was 3A, not 4A, competing with Mahomet and Oswego, not Whitney Young and Simeon. The competition wasn’t stiff enough for Rice to prove he could play with the big boys.

The body many would marvel at four years later had not yet developed. Rice was just a boy compared to many Big Ten guards. He still had his chubby cheeks. His arms lacked definition. At 6-foot-2 and 190 pounds, he needed to add strength.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Instead, many thought Rice’s calling was football. His sophomore season at Centennial, he backed up first cousin Mikel Leshoure at running back. Leshoure, an Illinois football commit, would eventually be selected in the NFL Draft. The News-Gazette’s Loren Tate wrote, “If ever there was a surefire Big Ten football prospect as a sophomore, Rice was it.” Rice, however, wanted to play basketball.

The problem was no one thought he could keep up.

***

Without a Big Ten offer, Rice chose to play at Drake, a Missouri Valley Conference school in Des Moines, Iowa, five-and-a-half hours northwest of Champaign.

Rice started in his first game and had a double-double (15 points, 10 rebounds) in his third. All season long, Rice was touted as the second-best freshman in the Missouri Valley, behind only Creighton’s Doug McDermott.

On Jan. 1, 2011, the two faced off for the first time. Rice shot 2-for-11 and scored seven points, McDermott shot 9-for-12, in addition to 9-for-9 on free throws, and scored 28 points. The score: Creighton 73, Drake 57.

A little more than a month later, the two went head-to-head again. This time Rice made 5-of-12 shots to McDermott’s 4-of-12, outscoring him 16 to nine. Drake won 67-64.

That first season, Rice led Drake in scoring, rebounding, steals and blocks. He shattered the Drake freshman scoring record. He was sixth in the conference in scoring, second for freshmen behind McDermott.

But Drake didn’t make the postseason. The Bulldogs lost in the first round of the Missouri Valley tournament, despite Rice’s 13 points and four blocks. Drake finished the season at 13-18.

In his second season, Rice improved his scoring (16.8 points per game), rebounding (5.8 per game), efficiency and the team finished 18-16. Drake made the Collegeinsider.com postseason tournament and, in his final game, Rice had 23 points, but his team lost 74-68.

By the end of his sophomore year, Rice was well on his way to being the school’s all-time leading scorer. After two years, he had scored 983 points. Had he kept pace, Rice would’ve scored 1,964 points, 307 more than the school record of 1,657. Rice had fallen behind McDermott’s level, scoring 16.8 points per game to McDermott’s 22.9. He likely wouldn’t have become a 3,000 point scorer. But he had bigger dreams than Drake.

***

In March 2012, following his sophomore season, Rice declared he was transferring. The first coach to reach out to him was John Groce, who had taken over as Illinois’ head coach a month before. Groce had recruited Rice to Ohio when Groce was the Bobcats’ coach. He had seen Rice have the impact of a Big Ten-caliber player while playing in the MVC.

Groce asked if Rayvonte wanted to come home. He told Rayvonte going to college at home wasn’t for everyone. Rice would see people he grew up with. He would be judged at a different level. But Rice, a lifelong Illinois fan whose mom made the drive to every game at Drake, wanted to come home.

Groce, trying to install an aggressive system, thought Rice would be a perfect fit.

“Rayvonte is an aggressive player on both ends of the floor who will fit in well with our style of play,” Groce said at the time.

With the decision to transfer, Rice had a year to improve his game and get fit. He had grown 2 inches since coming to Drake, but he had also gained 80 pounds. A 6-foot-4, 270 pound shooting guard wasn’t of much value in the run-and-gun system Groce wanted to play.

So, for Rice to be the hometown hero, he needed to hit the gym. He couldn’t take a day off, despite not being able to play basketball for another 18 months.

He knew when he got back, he would be on a team with a clear hole at shooting guard — a hole he would be expected to fill.

“Be patient. Your time is coming,” coaches would tell Rice.

He had a year to practice against Big Ten guards D.J. Richardson and Brandon Paul.

Rice moved home to Champaign, but his diet forced him to cut out most of his mother’s cooking, a cut that especially hit home on macaroni nights.

As Rice got his body into shape, the rumors started to swirl. “Rice is a man among boys in practice.” “Rice can still score against Big Ten competition.”

The fanbase heard the rumors. Was Rayvonte Rice the impact player the Illinois basketball program needed? Was he the native son who would bring the Illini back to the promised land of Big Ten Championships and NCAA tournament runs?

Groce said it was the best sit-out year he’d ever seen. Rice transformed from 267 pounds and 12.6 percent body fat to 231 pounds and 5 percent body fat.

With the weight loss, the body that football scouts raved about became evident. Basketball scouts began to wish they had seen the same thing.

Groce raved about Rice’s natural gifts.

“What makes Rice good?” Groce was asked.

“Size. Strength. Hands. Anticipation. Quickness. Explosiveness,” Groce said. “Want me to keep going?”

Rice was an anomaly in Big Ten basketball. He was bigger and faster than most competing guards. He clearly fit in. But that wasn’t all Groce saw.

“Most importantly, his mind. He’s a tough dude,” Groce said.

Rice was able to realize all of his work would come to fruition the first time he took the court for Illinois.

***

The first time Rice played as an Illini, he scored 22 points and grabbed nine rebounds.

In the nonconference season, Rice was the only consistent scorer. Without him, Illinois wouldn’t have at least three of its nonconference wins. His teammates helped out against the defensively challenged nonconference opponents, but he clearly stuck out.

After Christmas, Rice began hitting his stride, and Illinois appeared to as well.

At the United Center in December, Rice scored 28 points, including seven in 58 seconds to help the Illini come back from a 10-point halftime deficit for a 74-60 win over UIC.

In the first Big Ten game, Rice and Indiana’s Yogi Ferrell had a scoring duel, with Ferrell scoring 30 to Rice’s 29, but Rice’s Illini won in overtime.

Against Penn State, Rice led the Illini with 15 points as Illinois beat the Nittany Lions 75-55.

At 13-2 overall, Illinois reached No. 23 in the polls. Rice led the conference in scoring. If he wanted to score, he could.

Even against Wisconsin, one of the nation’s most stringent defensive teams, Rice had 19 points and nine rebounds, though Illinois lost 95-70.

It seemed no one could stop him, but he hadn’t faced the grind of the Big Ten.

After the loss to Wisconsin, Rice suffered a strained hip adductor. In a 49-43 loss to Northwestern in his next game, a noticeably hampered Rice had just eight points, his first single-digit scoring game of the season. With a healthy Rice, Illinois likely wouldn’t have been held to 43 points against a Wildcats team that allows 63 points per game.

The injury nagged and Rice struggled. In the next two games, he shot 3-for-9 and 5-for-15 but had 11 and 12 points. Against Ohio State, Rice had his first scoreless game.

As Rice’s injury continued to bother him, the Illini posted the worst shooting percentage in the country in January. Statistically they sported the worst offense in modern program history.

After the injury, it seemed the Big Ten figured out how to beat Illinois: Take away Rice.

Once healthy, he wasn’t that different than Northwestern’s Drew Crawford or Penn State’s Tim Frazier — putting up eye-popping numbers for a bad team.

Rice, unlike the transfers that came before him, could star in the Big Ten. Sam Maniscalco, Sam McLaurin, Trent Meachem, Alex Legion, the list goes on, but none of the players stood out in conference play. Rice could score and defend, but to win in the Big Ten, he needed help. And he wasn’t getting it.

His usage rate was rivaling his usage rate at Drake, as he was scoring about a quarter of his team’s points. If Rice couldn’t get Drake to win alone, he wouldn’t win being the sole scorer at Illinois.

“He needs some help,” Groce said in the middle of the losing streak. “I don’t think there’s anything else he can do. We need some other guys to be more consistent with their scoring and their shot-making.”

Finally, after a 24-point, nine-rebound effort by Rice in a 75-63 loss to Wisconsin — Illinois’ eighth straight — Groce inserted freshmen Kendrick Nunn and Malcolm Hill in the starting lineup, providing an offensive spark for the Illini. Both freshmen proved they could score, going for double digits in the 60-55 win over Penn State to break the streak.

Other teams had to concentrate their defensive efforts on someone other than Rice. He wasn’t double-teamed on every play. Rice immediately saw a difference.

“It helps when everyone is helping,” Rice said. “It doesn’t allow the other team to just worry about me, and just faceguard me. We take advantage of it.”

With the offensive help, Illinois won four of its last five games. The Illini beat three NCAA tournament teams: Nebraska, Michigan State and Iowa, with the wins against the Hawkeyes and Spartans coming on the road.

In the Big Ten Tournament, the Illini defeated Indiana again and pushed Big Ten regular-season champion Michigan to the brink, before a Tracy Abrams buzzer-beater fell short.

In the first round of the National Invitation Tournament, Rice, finally out of Big Ten play, had 28 points to singlehandedly fuel a 66-62 win over Boston University. His 15 points, which led all scorers, weren’t enough to top Clemson in the second round, with another Abrams potential game-winner falling short. He and Jon Ekey, who scored 11 points, were the only Illini in double figures. None of the other starters had more than six. He didn’t have enough help.

***

We finally understand what Rayvonte Rice is.

He can score. He can singlehandedly will the Illini to victory. But he can’t do it every game. On an off night, Illinois will falter if someone else doesn’t step up.

He can anticipate passes, popping them out, explode toward the ball and race toward the hoop, finishing with a monster dunk or a finesse layup.

But he’s not perfect. When going up for a one-handed jam against Michigan, Rice lost the ball and airballed what should’ve been an easy bucket. With 1:12 remaining, he drove to the basket, layed the ball up, and it rimmed out. Either basket could’ve been the difference in the one-point loss.

Rice is a proven shooter, but he’s so used to being the only player who can score that poor shot selection has limited his effectiveness, causing him to miss many 3-pointers that he shouldn’t be taking, whether they’re from deep or with a hand in his face.

The referees can have a direct impact on Rice’s effectiveness. If they call fouls like they did early in the season, Rice can drive in, get fouled and convert free throws. If they revert to the old system, like they did in Big Ten play, Rice isn’t nearly as effective, often losing the ball as he drives toward the basket.

But once Rice had help, he became relaxed. He became more effective and more efficient.

Illinois’ postseason encapsulated the season in just two games. Rice could will the Illini to victory against less-talented teams, but he couldn’t do it alone against those more talented.

With three double-digit scoring transfers waiting in the wings, help appears to be on the way. Senior Ahmad Starks is the all-time leader in 3-pointers at Oregon State. Junior Aaron Cosby shot 40 percent on 3-pointers and averaged 12.6 points per game against Big East competition while at Seton Hall. Sophomore Darius Paul was the MAC Freshman of the Year at Western Michigan and has proved he can knock down shots as a stretch four. Freshmen Kendrick Nunn and Malcolm Hill should continue to take steps forward.

In conference play, Rice was ninth in the Big Ten in scoring, fifth in rebounding (second in defensive rebounding) and fourth in steals. His shooting percentage improved significantly on 3-pointers and free throws. He fouled and turned the ball over less than in two years at Drake. He showed he was good enough, with help, to will Illinois to victory against Final Four-caliber teams.

Rice went from not good enough to play in the Big Ten to an above-average Big Ten player on an average Big Ten team. He became an offensive threat on an offensively challenged team and a defensive force for one of the nation’s best defenses.

It certainly seems like he is supposed to be here.

Johnathan can be reached at editor@dailyillini.com and @jhett93.