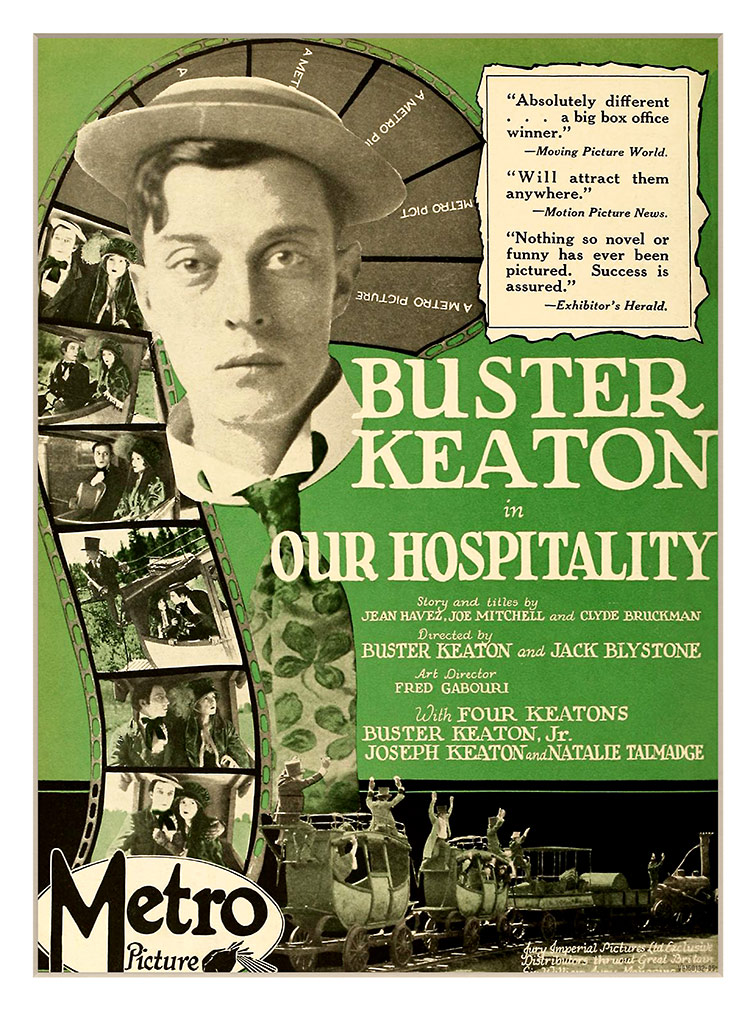

The silent comedy film “Our Hospitality” was released 100 years ago this November.

The film is the second feature directed by and starring Buster Keaton, one of the central silent filmmakers of his time alongside the likes of Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd.

Though perhaps better known for his more totemic works such as “The General” and “Sherlock Jr.,” “Our Hospitality” serves as a fascinating introduction to Keaton’s approach to feature filmmaking as well as an early introduction to his breathtaking stunt work and construction of intricate set pieces.

At approximately 75 minutes long, the film follows Wille McKay (Buster Keaton). Willie’s father was killed when he was an infant as a product of an empirical feud between the Canfield and McKay families.

Years later, with no knowledge of the feud, Willie decides to go back to his hometown to reclaim his father’s estate. Along the way he becomes acquainted with Virginia (Natalie Talmadge), who invites him to her home. Willie is unaware, however, that Virginia is a Canfield and that her brothers are looking to kill him.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Coming off of his first feature “Three Ages,” a feature-length film comprised of three discrete two-reelers — shorts comprising of two film reels in length — “Our Hospitality” is Keaton’s first real foray into the longer-length singular narrative film that would go on to dominate the rest of his directing career.

Nevertheless, the film uses this overarching narrative of the feud and Willie’s unawareness-turned-desperation as a general framework that allows for the creation of more individualistic gags and scenarios.

The opening stretch, which sees Willie and Virginia meet on a train, is rife with this kind of scene construction. As the train goes further and further across the country, Keaton plays with the instability of the terrain, changing train tracks and collapsing of carriages as sources to add short but focused comic gags.

Later gags, such as one extended sequence that sees Willie fishing at a nearby pond only for a waterfall to come battering down on him, coincidentally obfuscating him from the brothers who are out trying to kill him, are emblematic of how Keaton uses the extended narrative as a gateway towards isolated jokes that still effectively work at continuing the story.

Keaton taps into the inherent irony of the premise that a family could be so steadfast about their hospitality when welcoming a guest could, at the turn of a hat, launch into a hunt for a person that they do not know yet have been told to hate. Keaton takes this irony and imbues it into the construction of the gags themselves.

The visual comedy of the film is entertainingly exaggerated, something that has become immediately identifiable as part of silent-film language. The result is something very cartoon-like, using increased motion and wider shots as a way to communicate elaborate and stunning visual stunts while also highlighting the comedy within.

However, the film ultimately suffers at times as a result of this structure. The first bit with the train is fun, though the escalation of the jokes feels less developed. It is only when the cat-and-mouse game between Willie and the Canfields begins — around a half hour into the movie — that the momentum starts to build.

The film’s final act, which sees Willie try to evade the Canfields on a cliff near the waterfall, is an incredible achievement.

It is also the first in a later pattern among Keaton’s filmography in which the final set piece is so elaborately constructed and exciting that it feels as if the rest of the film is slowly leading toward that point.

This isn’t to say that the rest of the film is unengaging, but when the waterfall sequence starts, you do feel a noticeable jump in energy and scale.

Keaton merges his constructed features of the environment, whether it be the rocky cliffs and waterfall, with background environments lending to this sense of height and danger. The final climax of the sequence, where Buster catches Virginia as she falls off the waterfall by swinging on a rope, is undeniable and mind-boggling.

Keeping the camera fixed and allowing for a wider shot lends itself to the pendulum-like motion as he swings on the rope and lets us watch as he moves in and out of the onslaught of the waterfall’s downpour.

At the time the film was a success and served as a strong jumping-off point for Keaton’s career as a director.

A century later, the film’s reception and status have only grown. As both a turning point for Keaton, as well as a shift in filmmaking towards larger-scale and more ambitious projects, the film remains important.

The film has also been adapted numerous times, most notably in 2010 by “RRR” filmmaker S.S. Rajamouli.

At 100 years old, “Our Hospitality” remains an accessible and entertaining work from the silent era. Blending ambitious stunts, unique visual gags and an absurd narrative, the film is a slightly unbalanced yet engaging achievement. Like all of Keaton’s films, it is under the public domain and can be watched for free almost anywhere.