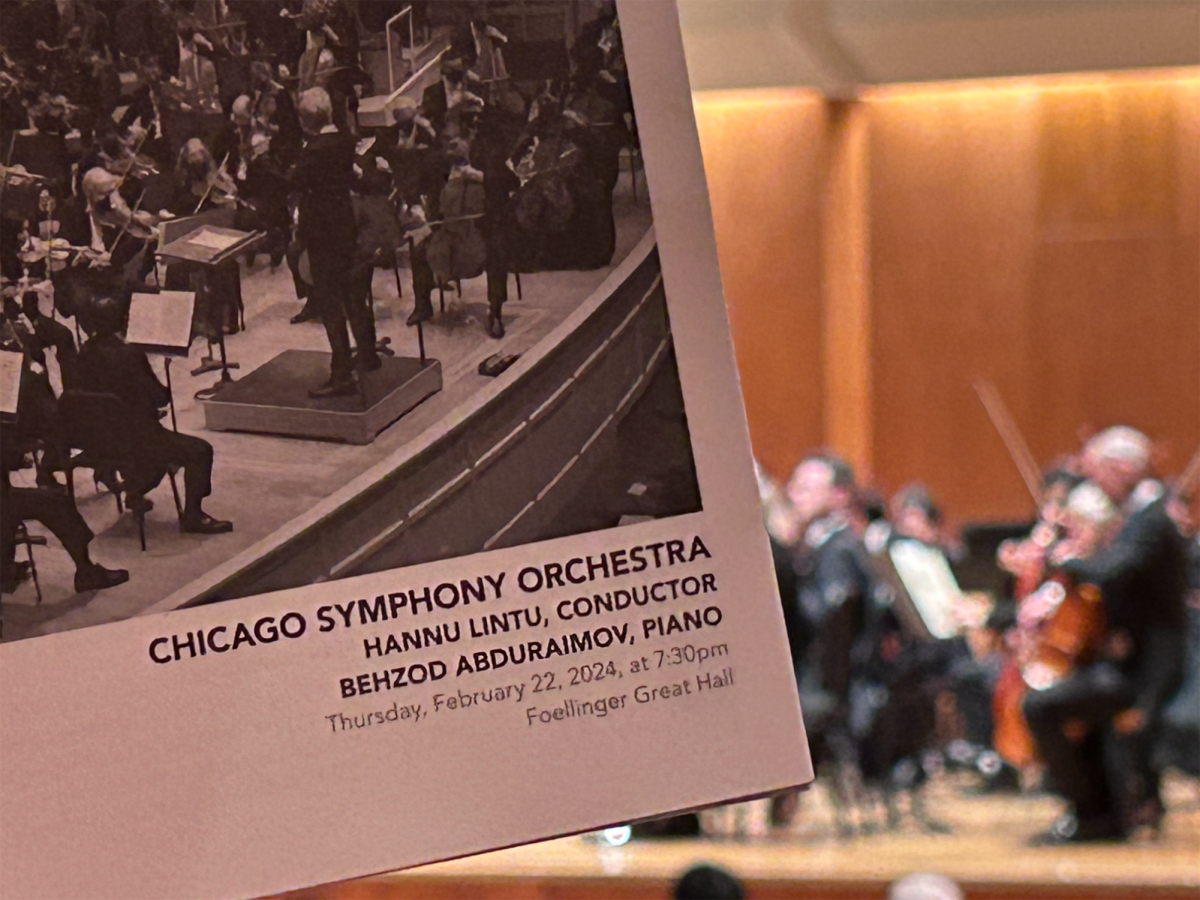

The Champaign-Urbana community packed Foellinger Great Hall at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts in anticipation of a visit from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on Thursday evening.

The program was highlighted by works from Russian-born composers, ranging from Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s dramatic and intense “Piano Concerto No. 1” to an ethereal “Prelude to ‘Khovanshchina.’”

“Ciel d’Hiver” — Saariaho

A notable exception to the Slavic theme was the opening piece — a contemporary orchestral movement from prolific Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho.

Saariaho’s work began with a strikingly gloomy melodic dialogue from a single piccolo and the concertmaster, which was supported by a slowly swelling backdrop of soft, unyielding strings and occasional percussion.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

As the movement built its way to its peak, the hall was filled with fluid, almost unsettlingly dissonant soundscapes. A crescendo crept over the audience; so slowly that it almost went unnoticed.

Just as the piece settled into a sense of unease, the orchestra returned with occasional reminders of the melodic structure from the beginning.

Saariaho, who was born in 1952 and passed away in June of 2023, was known for pieces that seemed to imitate natural phenomena. According to an interview with Finnish musicologist Pirkko Moisala, Saariaho was gifted with an ability to communicate seemingly intangible sensations through music.

“The visual and the musical world are one to me,” Saariaho said. “Different senses, shades of color, or textures and tones of light, even fragrances and sounds blend in my mind. They form a complete world in itself.”

“Piano Concerto No. 1” — Tchaikovsky

Following a brief pause, the CSO welcomed Uzbek pianist Behzod Abduraimov onto the stage to perform Tchaikovsky’s “Piano Concerto No.1.”

For lack of better phrasing, this concerto is seemingly larger than any single pianist. As one of the most well-known works across all classical repertoire, the piece needed no introduction.

The skill necessary to follow the phenomenal list of performers who have nurtured this piece to its current glory is not easily obtained. According to the program, Abduraimov studied under several well-known pianists hailing from across the former Soviet Union — and his expert tutelage showed.

The agile and passionate musicality of Abduraimov was complemented and elevated by an exceptionally nuanced performance from the CSO. The first movement of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto, “Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso,” was tinged with soft, comforting orchestral chords and sweeping arpeggios from the soloist.

The main theme of this movement was repeatedly relayed to the audience by piano and shimmering strings. An ideal opener for the roof-raising classic, this section was a sonic treat and eased the audience into future Russian folk themes with its celestial harmonic structure.

As the audience was welcomed through the gates of the second movement, the orchestra’s wind section was allowed an opportunity to demonstrate its chops. The flute solo that introduced Abduraimov into the melodic framework was buttery, fluid and romantic.

Once again, the masterful strings were something of a guide for other sections. Strings provided a gorgeous and subtle pizzicato accompaniment that fluffed the pillow upon which the soloist would later place a stunning scherzo.

Throughout each movement of the concerto, the influence of Russian folk music was evident, but the third was the most clear display of Tchaikovsky’s heritage. At every turn, Abduraimov demonstrated that he was the ideal choice for this performance through his nimble control of the instrument.

“Behzod Abduraimov combines an immense depth of musicality with phenomenal technique and breath-taking delicacy,” CSO’s website wrote about the pianist.

Prelude to “Khovanshchina” — Mussorgsky

Modest Mussorgsky, an innovator of Russian music during the Romantic period of classical music, spent about eight years in the late nineteenth century writing an opera entitled “Khovanshchina.”

The composer died following the completion of the libretto and piano scoring, meaning that he was never able to set “Khovanshchina” to an orchestra. The third piece on Thursday’s program was the result of an orchestration written by fellow Russian composer, Dmitry Shostakovich.

According to Mussorgsky, the Prelude, also known as “Dawn over the Moscow River,” intended to depict “matins at cock crow, the patrol, and the taking down of the chains (on the city gates).”

As was the case on several of the evening’s pieces, a Russian folk-reminiscent theme was presented as an introduction to several variations. The five-minute-long piece was short and sweet when compared to the rest of the program.

The CSO winds were on display in this piece, with sweeping melodic lines depending strongly upon their precision and synchronization. As usual, the professionalism of the performers made the evening a feast for the ears.

“Symphony No. 9” — Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a prominent Russian composer in the twentieth century. So prominent, that he was awarded several governmental awards by the Soviet Union for his contributions to the culture of the region.

According to Shostakovich, the symphony is extremely demanding.

“My Ninth Symphony is very difficult to perform,” Shostakovich said. “This symphony also has a number of solos, there are big solos for all the woodwind instruments, the trumpet, the trombones and the violin.”

The first movement of Shostakovich’s ninth symphony was an energetic, folky romp with mocking undertones and a strong sense of humor.

The winds demonstrated their talent once again in this piece, with a spirited dialogue between the piccolo and low brass piercing through the melodic structure of the movement.

The second movement was moodier, with a weighty, sentimental quality hanging over the modified waltz theme. The CSO’s conductor for the evening, Hannu Lintu, was extremely expressive, conducting the movement using fluid motions throughout his entire body. There were instances where Lintu seemed to almost levitate from his spot on the podium.

The final three movements of Mussorgsky’s ninth symphony were played consecutively, with very short pauses.

Following the second movement, the orchestra seemed to gradually build to some sort of a villainous climax, but the climb stopped just short of the peak to make way for an intense adagio and a consequent bright principal theme.

At the finale, the energy of the music was particularly peppy, with an intensely dance-like feel that was only enforced by Lintu, who led by example.

Closing thoughts

This program was nothing short of sensational. The drama of Mussorgsky and Tchaikovsky’s Russian Romanticism was refreshing alongside the complex harmonies of “Ciel d’Hiver” and the intensity of an iconic Shostakovich symphony.

If you are ever presented with the opportunity to see a professional orchestra perform live, particularly one with the critical acclaim inherent to the CSO brand, do it. The level of control the instrumentalists have over their instruments is in its own league.

Champaign frequently welcomes world-class musicians at its various venues, so keep your eyes peeled for tickets.