To say Wes Anderson has a fascination with stories would be almost reductive. Over his expansive career, the filmmaker has experimented with metanarrative and stories-within-stories to a hyperbolic degree.

Whether it be the articles that constitute the final edition of “The French Dispatch” magazine or the teleplay within the television taping of “Asteroid City,” Anderson seeks to uncover human truths buried within the artifice of our own creations.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” “The Swan,” “The Rat Catcher” and “Poison,” four new short films from Anderson, are no different. Released on Netflix daily from Sept. 27 to Sept. 30, each short film adapts a separate story from the author Roald Dahl.

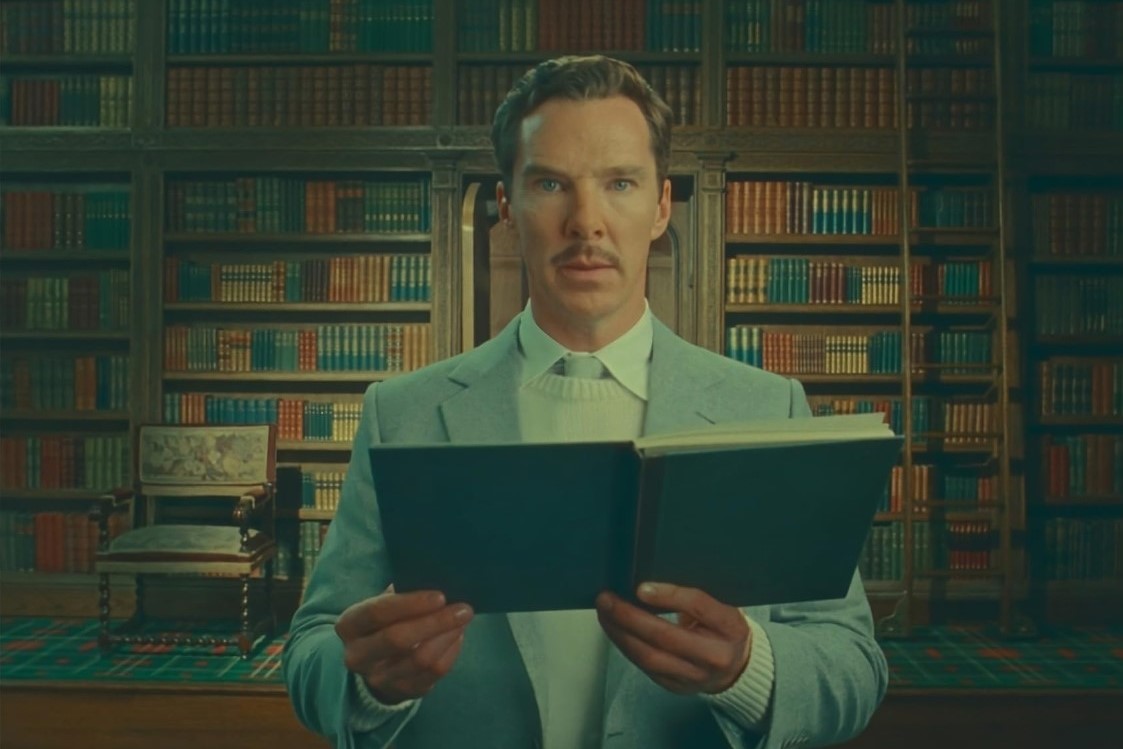

Of the four shorts released, “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is the flagship. The film follows Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch) as he comes across an account written by Z.Z. Chatterjee (Dev Patel), a doctor from Calcutta, regarding a man who supposedly had the supernatural gift of being able to “see without his eyes.”

Sugar, a wealthy narcissist, hopes to learn this precognitive gift in order to cheat in casinos. As the film goes on, however, Sugar finds himself puzzlingly conflicted about using this gift for greed.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

If “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is a heartwarming story that argues anyone can be a good person, the other three shorts work to challenge that claim by depicting humanity as inherently cruel and violent.

In “The Swan,” Peter Watson (Rupert Friend) recounts the traumatic story of the day he was terrorized by two bullies.

“The Rat Catcher” showcases the bizarrely horrific interaction between members of a town (Rupert Friend and Richard Ayoade) and the Rat Catcher (Ralph Fiennes) they call to exterminate rats living in a local haystack.

“Poison” follows an Indian man (Dev Patel) and a doctor (Ben Kingsley) during British rule as they try to help a man (Benedict Cumberbatch) who believes there is a poisonous snake asleep on his stomach.

Anderson is no stranger to adapting Dahl’s work, having already done so once with his 2009 animated feature “Fantastic Mr. Fox.” With these new shorts, Anderson seeks to expand the scope of his adaptation even further, taking the prose that would ordinarily inform the visual language of the film and baking it explicitly into the text of the script.

Characters aimed directly at the camera monologue Dahl’s lines almost verbatim. They describe other characters and the situations they are in as well as the nature of the environment around them.

All the while, Anderson brings increased attention to the artificiality of the sets, with each new location being created almost in real time as the camera moves within the scene or from one scene to the next.

The result is dazzling. It is such a joy to watch the mechanisms of the set operate in real time. Layered walls are shuffled in and out of frame by extras, props are brought in to accompany the narration of the prose, the color of the lights modulates almost as a function of the characters’ internal emotions and wooden doors hinge out of organic set dressing.

This creates a distinctly theatrical quality that serves to underscore Anderson’s desire to portray stories as powerful and personal affectations of our own cognitive assembly.

The performances are all stellar. Cumberbatch, as expected, acts as if he was born to be a part of Anderson’s films. His timber baritone and exaggerated mannerisms in “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” fit in perfectly with the heightened reality around him.

Patel, however, is the breakout here. His cadence fits the rhythm of Dahl’s prose like a glove, and the intensity of his expressions elevates the emotion and tension of each scene he is in. Of all the performers in this troupe, he is the one who should act in another Anderson feature.

Also noteworthy is the cinematography. Anderson has always shot on film, yet here, he chooses to break from his use of 35mm in his theatrical movies and uses 16mm film stock. The result is breathtaking.

The added softness of the 16mm film brings a painterly atmosphere to the backgrounds while also forefronting the rich saturation in skin tones and costuming. It also compliments the design choice of each respective set while highlighting the specificity of the pastel color palettes and the uniqueness of the architectural spaces.

In recent works, Anderson has contextualized his stories through the perspective of their writers. Whether this be the author of the novel “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” the staff that makes up “The French Dispatch” or the playwright of “Asteroid City,” Anderson is singularly fascinated by the way authorship reflects itself in artistic and literary endeavors.

With these new shorts, Anderson intertwines his narratives with Roald Dahl himself, played by Ralph Fiennes, interjecting his own prose as an authoritative and almost omnipresent voice on the proceedings as we see them.

The addition of Dahl as a character refocuses each short through the lens of its creator. In doing so, Anderson is able to explore the paradox and contradiction of the writer to great effect.

In juxtaposing “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” with three bleaker stories, Anderson contends with Dahl’s legacy and attempts to uncover how the darkness within the writer can be reflected by his words.

As more people contend with the growing inscrutability of Anderson’s Russian-doll-like framing structures and preoccupancy with precise storybook visuals over richly human characters, these shorts reaffirm that despite the artificiality in his presentations, you cannot deny the truths at the center of them.