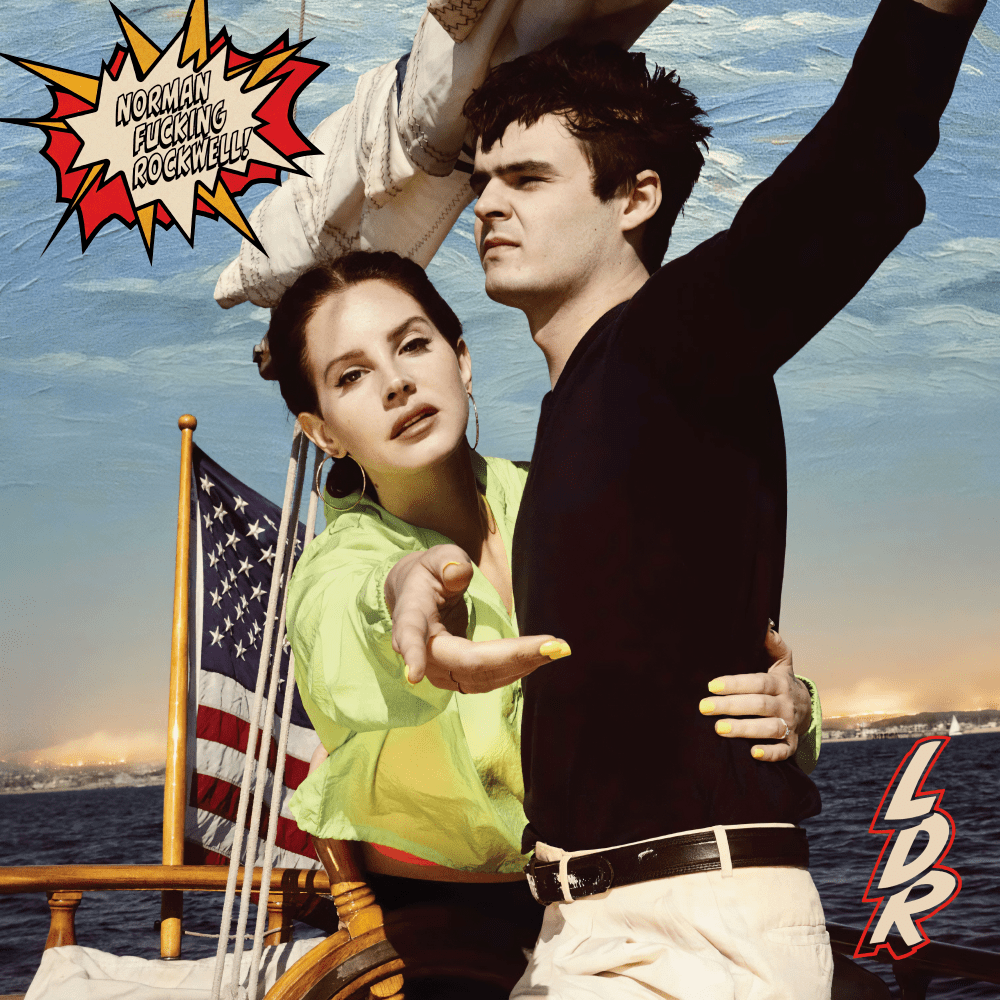

“Godd—, man child,” Lana Del Rey sings against the trite piano chords that begin her fifth studio album, “Norman F*****g Rockwell!”

It’s an illustrious start to the album, the silky strings and stripped piano chords giving way to lyrics saturated with dry wit and dark poeticism.

“You f—–d me so good that I almost said ‘I love you.’”

She sets the tone for what is undoubtedly one of her most vulnerable records to date — her words crash over you without warning, drowning you in devastating melancholia and short bursts of ecstasy.

Del Rey breaks all conventions of her previous records; the goal is not to aesthetically please, as people accused her earlier albums of doing, but to reflect and be self-aware, making Del Rey more visible and more vulnerable than ever.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

It’s bare but unrestrained, leaving behind the glamorous pop beats of previous albums and settling for a sound matching the soft rock of the ‘70s.

Del Rey is a poetic songwriter who creates beauty by writing and turning those words into songs. She’s impassioned — maybe the “f—–g” in the title is a feeling of exasperation; she’s tired of people telling her who she is and who she’s trying to be.

Or maybe the “f—–g” is a hopelessness of the American dream — a dream that exists for so little.

According to Pitchfork, Norman Rockwell illustrated paradisal images of American life, as he spent 50 years at the Saturday Evening Post with Americana propagandists.

But Del Rey knows better than to believe the manufactured American dream that Rockwell clung to in his paintings; she knows that living is more than just a picturesque utopian fantasy.

“Norman F*****g Rockwell!” is a winding tapestry of everything in her life: men, alcohol, drugs, love, sex, sadness and everything else. It’s resilient and elegant, a confession of being alive and everything that comes with it.

The songs are cavernous, deep holes of thorny resignation drenched in unhappiness but still hold a glimmer of hope.

“Cinnamon Girl” may be the most expansive of these caverns. It’s majestic, with soaring piano chords and lush strings; it’s a ground-swelling song that eats you up and spits you back out before you even realize what happened.

“There’s things I wanna say to you/ But I’ll just let you live/ Like if you hold me without hurting me/ You’ll be the first who ever did,” Del Rey sings, her voice laced with defeat.

It’s a haunting song of Del Rey fighting for the attention of a man who will never be good enough for her. Consumed by the drugs and continuously pushing her away, Del Rey fights her way back into his life over and over again. It’s an endless cycle with no winners, only consequences, especially for Del Rey.

She’s not a weak woman, but she’s damned to love a man who hurts her, and maybe that’s the worst kind of pain for someone like her.

On “The greatest,” Del Rey is funny, with stark humor that may fall flat at the feet of some but resonate heavily in the minds of others. The song is about reminiscing — remembering people, times and places. It’s looking back at the best parts of life and grieving the loss of culture.

She sings about missing New York and its music, dancing, her friends, Long Beach and the bar where the Beach Boys went. She notes how Hawaii missed a fireball, climate change in Los Angeles and that “Kanye West is blond and gone.”

Though the lyrics are simplistic and geared more toward the uncomplicated language of millennialism, their clever elaboration holds immeasurable meaning.

“I’m facing the greatest/ The greatest loss of them all,” she sings, her voice breathy. “The culture is lit and I had a ball/ I guess I’m signing off after all.”

Her lyrics are sincere in their longing, as the instrumentation whirls with cinematic lavishness and shadowy piano chords that conclude the song.

“hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but I have it,” is the final song on the album and perhaps the most burdened.

It’s balmy and sweet, a swinging, tripping, rhythmic beauty drenched with vulnerability and elegance. Del Rey’s slanted lyrics are unique to her, referencing Sylvia Path throughout the sparse piano chords.

“Don’t ask if I’m happy, you know that I’m not/ But at best, I can say I’m not sad/ ‘Cause hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have,” Del Rey sings with muted stoicism.

In “Norman F*****g Rockwell!” Del Rey leaves the glamor behind, replacing it with carefree introspection and vivacity that only she is capable of.

The album’s narration is impeccable, each song balancing hope and despair, love and pain. It’s sublimely profound, a blank canvas to explore the vast Los Angeles landscape and the trappings of life.

Del Rey creates an album that is a sore wound — a breathless display of emotional disorder — composed of staggering piano melodies and unearthly harmonies with dissonant lyrics that define her as one of this generation’s greatest songwriters.