Hidden Gem: ‘Blue Collar’ (1978)

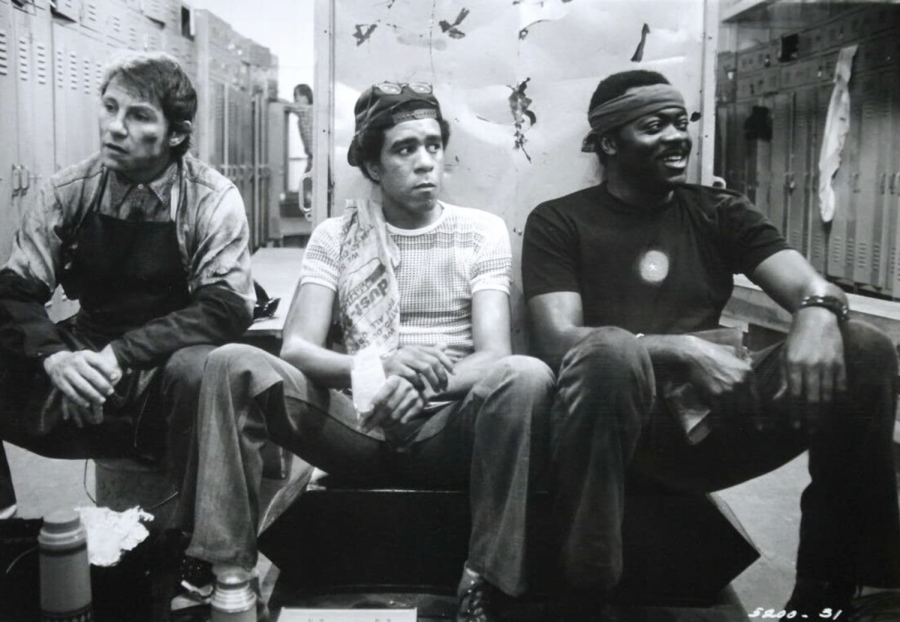

Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto, and Richard Pryor star in the film “Blue Collar”. The movie was released on Feb. 10, 1978

Jul 27, 2021

For years, Paul Schrader was known in Hollywood as one of the finest screenwriters who had never been nominated for an Oscar. That held true until 2017 when his screenplay for “First Reformed” received a nomination. During the 1970s and ‘80s, Schrader wrote four screenplays for Martin Scorsese hits, including “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull.” In addition, he wrote and directed the popular remake of “Cat People” and the box office hit, “American Giglio.”

Schrader’s first attempt at directing was in 1978 overlooked cynical social drama, “Blue Collar.” The film has the look and feel of a Scorsese film. Co-written with his brother Leonard Schrader, it starred Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto as three disgruntled auto workers who strike back at the bureaucracy by stealing from their union. In his original review of the film, Roger Ebert called “Blue Collar” a “stunning debut.” He gave the film four stars.

Zeke Brown (Pryor), Jerry Bartowski (Keitel) and Smokey James (Kotto) are fed up with their working conditions as assembly-line workers at the Checker Auto company and even more disturbed by their union representation. Their union steward and leaderships’ double talk and inability to attend to real issues have them more than just frustrated. They are loyal union workers who were proud to have participated in a 73-day strike several years ago and won significant wage increases.

Zeke is a married guy with three children who had recent troubles with the IRS. Jerry is also a seemingly happily married family guy who even works a second job pumping gas and has a teenage daughter who needs braces. Smokey is an ex-con who has a reputation for hosting late-night cocaine parties with beautiful young women. One day, they are approached by a local college instructor who’s doing his doctoral work on unions who tells them their local 291 AAW union is one the most corrupt in Michigan.

The trio, who each have seven to 10 years of work experience in the auto industry, are frustrated with the American dream. They are always broke, owing money to someone, and barely scraping by. When they cook up a scheme to rob their union office’s safe and possibly gain thousands of dollars, the film turns into a working-class caper film.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

After they break into their union’s safe, they are shocked by the small amount of money they find, something less than a few thousand dollars. They are also astonished to discover a notebook ledger with lists of numerous high-interest illegal loans made by disreputable organizations and links to organized crime groups. With the notebook, the trio thinks that they can really change the union leadership either by turning the notebook over to the media or blackmailing the union leadership, revealing their possession of the book for a large sum of money.

All their plans turn sour, and union leadership sends thugs to threaten each individually. Eventually, friend turns against friend, and Smokey is killed in a “so-called” industrial accident in the paint shop. The story’s cynical conclusion reveals that those in power always have a plan to keep the little man in his place. And in the meantime, Schrader shows a large Goodyear sign that proudly proclaims the running total of cars being manufactured that year. In 1977, over five million new cars were made.

The Schraders’ script is filled with realistic dialogue and gritty natural performances. Kotto and Keitel are typically strong and believable. But it’s Pryor, who was mostly known for his slapstick comedic role, who is most effective in this rare, serious and dramatic role as Zeke. In several key scenes, Pryor is in top form, giving his advice to an older African-American autoworker, who simply goes along with management to protect his job, and then standing up to union leadership when they try to appease him with a steward position if he cooperates with them.

“Blue Collar” may not have been a box office success in its original release, but its realistic message about the struggle of the average working man resonates years later. I count myself so fortunate to have met and chatted with Schrader when he appeared at the April 2008 Roger Ebert Festival in Champaign.