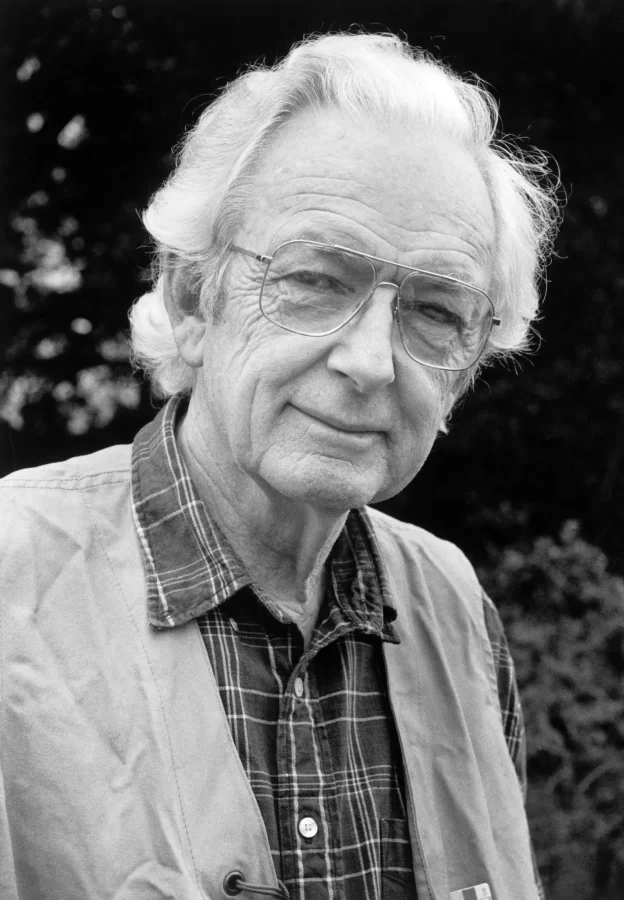

Wayne Miller expressed ‘the oneness of man’ in his frontline photography

Photo courtesy of Magnum Photos

Wayne Miller was photographer for The Daily Illini and The Illio, and has had an extensive career afterwards from photographing World War II and publishing a book “The World Is Young.”

Apr 5, 2022

For photographer Wayne Miller, his work was a way to showcase people as they were, in the hopes of showing how similar humans are to one another.

“We may differ in race, color, language, wealth and politics. But look at what we all have in common — dreams, laughter, tears, pride, the comfort of home, the hunger for love,” Miller wrote in the intro to one of his photography books.

Miller’s career as a photographer took him to the frontlines of World War II, the destruction of Hiroshima following the dropping of an atomic bomb and the Black communities of Chicago’s South Side in the 1950s.

He was an assignment photographer for LIFE Magazine and also contributed to Ebony and National Geographic throughout his career. Alongside his mentor, photographer Edward Steichen, Miller helped curate the renowned photographic exhibition, “The Family of Man,” which drew record-breaking numbers in the countries it toured in.

The Chicago native was born in 1918 and died in 2013. Miller studied banking at the University and was a photographer for The Daily Illini and The Illio. He graduated in 1940 and attended art school in Los Angeles before enlisting in the U.S. Navy.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Miller was part of a photography unit led by Steichen, traveling through the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to capture the war.

“I was excited, ambitious, and afraid all the time,” he said about his wartime experience in Ken Light’s 2000 book about documentary photographers, “Witness in Our Time.”

Miller was one of the first Western photographers to photograph the destruction at Hiroshima in 1945, when the atomic bomb dropped. He called it “the ultimate denial of sanity.”

After the war, Miller returned to Chicago as a freelance photographer. With fellowships he received from the Guggenheim Foundation, Miller started a two-year project photographing Black Americans in Chicago’s South Side.

The photos, capturing the everyday lives of post-war Black migrants from the South, captivated many photographers at the time, including Gordon Parks who saw himself reflected in Miller’s work. Celebrities like Ella Fitzgerald and Lena Horne appeared in the photos, but the vast majority were of people in their homes, laughing at local bars or making a living.

“(Miller) was simply speaking for people who found it hard to speak for themselves,” Parks wrote in the introduction of Miller’s published compilation of the photos.

Speaking on his work in 2000, Miller said he was uncomfortable with his then-ambitions to capture such a wide range of human experience.

“But I’m consoled by the knowledge that the whole picture can’t be contained in the files of any one photographer,” Miller said. “The subject is too vast, too complex, too diverse and too mysterious.”

After completing this project, Miller was contacted by his mentor, Steichen, to assist with curating a photographic exhibition, “The Family of Man,” which the Museum of Modern Art called “a forthright declaration of global solidarity.”

Miller told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1997 that he and Steichen looked at 4 million images and settled on 503, with the objective of showing the people of the world all that they had in common.

“This was not an exhibit of fine photographs. This was an exhibit of photographs that expressed the common theme of the oneness of man,” Miller said.

Included in the exhibit was one of Miller’s own photographs depicting his wife, Joan, giving birth to their son and Miller’s father as the doctor delivering the child. As a centerpiece of the exhibit, the image was included in a time capsule aboard the Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1971.

Miller was later inspired by “The Family of Man” to begin a project photographing his own children growing up in Orinda, California. In 1958, he published the photos in his book, “The World Is Young.”

Miller wrote in the book that he wanted to look with children rather than at them, hoping to capture their early life experiences.

“Being on the same level, I decided, creates understanding,” Miller said.

Miller was a long-time member of the American Society of Magazine Photographers and was named its chairman in the summer of 1954. He was also a member of Magnum Photos in 1958 and served as its president from 1962 to 1966.

He retired professionally in the ’70s, dedicating his time to environmental work. Miller helped develop award-winning environmental education programs for the National Park Service and co-founded the Forest Landowners of California organization, which lobbied for state laws aimed at forest preservation.

In 2000, when asked why he retired so early, Miller said he had spent most of his life as an observer of people’s lives.

“I wanted to be a more active participant in the world, no longer just a fly on the wall watching the world through my viewfinder,” he said.

Above all, Miller said his primary goal throughout his career was always to show people as-is.

“The common thread throughout my work is trying to photograph the individual,” he said.

“I’m not saying they’re bad or good. I’m just trying to show the world as they saw it and felt.”