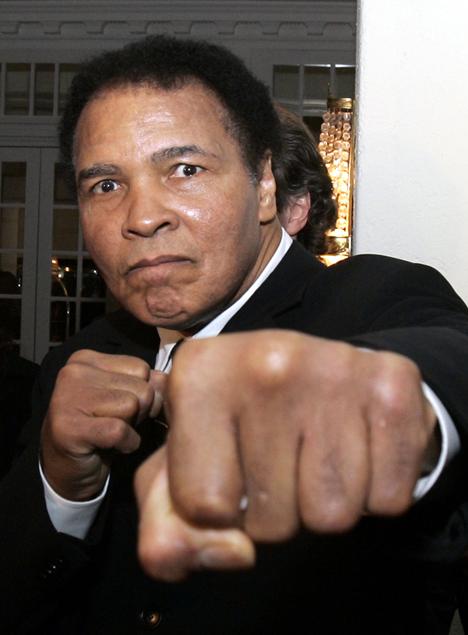

Ali turns 65, continues to fight Parkinson’s

Jan 17, 2007

The images are unsettling at best, upsetting at worst. The world, after all, remembers what he once was.

Muhammad Ali trembles and has to be wheeled to a ringside spot to watch his daughter fight in New York. A frail Ali needs to be supported by basketball player Dwyane Wade at the Orange Bowl in Miami.

The voice that once bellowed that he was “The Greatest” is but a whisper now, and he communicates mostly with facial expressions.

His body is ravaged by Parkinson’s disease and the effects of recent spinal surgery. He tires easily. His mind, though, remains sharp and clear, and his passion for people hasn’t faded with age.

Ali turns 65 on Wednesday. The heavyweight champion who shocked the world is a senior citizen now, eligible to collect Social Security.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Like many other retirees, he has moved from Michigan to the desert to be out of the cold.

Visitors to the home in a gated area of Scottsdale, Ariz., that he shares with his fourth wife, Lonnie, often find him absorbed in the past, watching films of his fights and documentaries on his life – and Elvis movies.

Even more, he loves to watch himself talk.

“Muhammad is a little sentimental. He likes looking at older things. He likes watching some of the interviews and saying some of the crazy outrageous things he used to say,” Lonnie Ali said. “Sometimes I think he looks at it and says, `Is that me? Did I really say those things?'”

Those were the days when Ali still floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, when he added to his legend by defying the odds to beat George Foreman in Zaire and Joe Frazier in the Philippines.

“Rumble young man, rumble,” cornerman Bundini Brown would yell to him.

That young man’s face is now distorted by Parkinson’s, making him look far older than he is. Now, instead of the “Ali Shuffle” that once dazzled the boxing world, he is reduced to sometimes using a walker, the result of surgery to help correct spinal stenosis, the narrowing of the spinal canal, which causes compression of the nerve roots.

Some days are better than others. Ali reads fan mail every now and then and painstakingly signs autographs with his trembling hand. Sometimes, mostly in the morning before his medication kicks in, the family can understand every word he says.

“We give him enough meds to make his day go well enough, but not enough to make him look absolutely normal,” Lonnie Ali said. “He would look better if we did, but we don’t want to. We don’t want him on too many medications.”

His birthday will pass with calls from his nine children and other relatives. Ali’s only request to mark the occasion is a trip to one of his favorite magic shops so he can pick up a new trick or two to show visitors.

One of his daughters, Hana, says no one should feel sorry for him.

“People naturally are going to be sad to see the effects of his disease,” she said. “But if they could really see him in the calm of his everyday life, they would not be sorry for him. He’s at complete peace, and he’s here learning a greater lesson.”

The man who made headlines and countless television highlights with his predictions and boxing prowess can’t really talk about himself anymore.

But others can.

The Daughter

Hana Ali listens often to the tapes, the ones her father made as an audio diary in 1979 when she and her sister, Laila, were little girls. On them, Ali’s voice is strong, his opinions certain.

“This is Muhammad Ali making a tape for future reference explaining what’s going on in the world,” it begins.

Ali talks about his efforts to mediate the Iranian hostage crisis and meeting kings from different nations. He gives his thoughts on war and peace, and he has a talk with George Foreman on God and religion.

“Sometimes I have to stop listening because I get in this time warp thing,” Hana said. “It’s all him in his own words.”

Of all his children, she may be the closest to her dad. She wants to take nursing courses so she can help care for him.

“He needs people like we need the air to breathe,” she said. “He knows how great he is, but at the same time he’s very humble. He’s shocked to see how people still love him and remember him. You see his eyes light up, and it takes him back a moment when they chant, ‘Ali, Ali.’ It’s like charging a battery up.”

Some days, Hana says, her father has more energy than others. Some days he’s able to talk.

No one knows why. It just happens.

“Every now and then you catch yourself feeling bad,” she says. “But he’s here, and he has a healthy, strong spirit and soul and mind, and that’s what is important.

“He always says he’s lived the life of 100 men. He got to see the world and do all these things. He has no regrets.”

The Inner Circle

Gene Kilroy traveled the world at Ali’s side. His official title was business manager, but Kilroy was known to most as the man who got things done.

He sheltered Ali from anyone trying to make a quick buck off him and took care of the people around him. For years, he was the lone white man in the champ’s entourage.

“I consider myself one of the luckiest guys in the world just to call him my friend,” Kilroy said. “If I was to die today and go to heaven it would be a step down. My heaven was being with Ali.”

On the walls of Kilroy’s office at the Luxor hotel-casino in Las Vegas are pictures of him and Ali taken around the world. Kilroy tells stories easily — the time he and Ali landed in the early-morning darkness in Zaire for Ali’s fight with Foreman only to find several thousand people waiting.

Ali turned to Kilroy and asked him whom the people of Zaire hated most.

“I told him white people. He said, ‘I can’t tell them George Foreman is white,'” Kilroy recalled. “Then I said, ‘They don’t like the Belgians, who used to rule Zaire.'”

Ali stepped out on the tarmac, called for quiet and yelled:

“George Foreman’s a Belgian!”

The crowd erupted, chanting “Ali boma ye, Ali boma ye.” Translation: “Ali, kill him.”

Kilroy worries about his old friend. He frets about his health and believes Ali shouldn’t travel so much. He cried the last time he saw Ali, a year ago in Berlin.

“He had a belief and a goal in his life. He wanted to see freedom, equality and justice for the black man,” Kilroy said.

“The artist, Leroy Neiman, said it best: Whoever touched Ali’s robe was a better person for it.”

The Opponent

Larry Holmes was proudest of the black eye.

He got it as an amateur the first time he stepped into the ring for a sparring session with Ali, at his training camp in Deer Lake, Pa.

“I didn’t want to put ice on it,” Holmes said. “Having him give me a black eye meant a lot to me.”

Holmes would later give Ali much worse. The two met on Oct. 2, 1980, at Caesar’s Palace, with Ali lured out of retirement to fight a former sparring partner who had become the heavyweight champion of the world.

Ali had given him his first chance in boxing, but Holmes had a job to do against the aging former champion, who grew a mustache before the fight and presented himself as “Dark Gable.”

The fight was lopsided from the opening bell. Holmes was young, fast and strong. Ali was a shell of himself and took a beating until he finally quit on his stool after the 10th round.

“He was like a little baby after the first round,” Holmes said. “I was throwing punches and missing just for the hell of it. I kept saying, `Ali, why are you taking this?'”

“He said, `Shut up and fight. I’m going to knock you out.'”

When the fight was over, Holmes and his wife went upstairs to pay their respects to Ali. In a darkened room, Holmes told Ali that he loved him.

“Then why did you whip my ass like that?” Ali replied.

Holmes hasn’t seen Ali recently but said he heard he was down to 185 pounds.

“I can’t just say Ali was the greatest because there were so many great fighters out there. I can’t say he was greater than Marciano, Louis, Dempsey and everyone else,” Holmes said.

“A lot of it today is that people feel sorry for him because he’s got that Parkinson’s or whatever is wrong with him. They feel he doesn’t have too much longer to live, and they want to be part of the legend.”