Letters to Hitler: New book spotlights 300 letters to the Nazi dictator

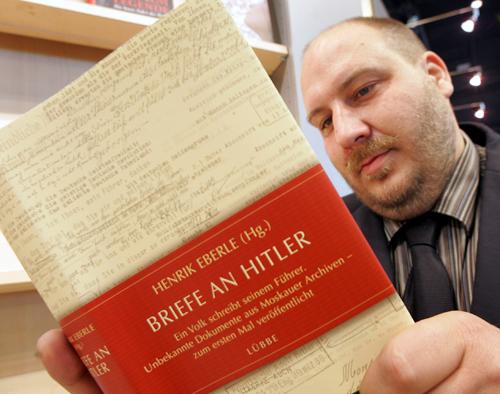

Author Henrik Eberle is seen with his book “Briefe an Hitler” (“Letters to Hitler”) at the Book Fair in Frankfurt, central Germany, Wednesday. Historian Eberle has compiled 300 letters to Adolf Hitler in his book after he examined more than 20,000 of them Michael Probst, The Associated Press

Oct 11, 2007

BERLIN – At first glance, the letter carefully printed in a child’s hand seems innocuous, nothing more than the expression of a young crush: “I love you so much. Write me – please. Many greetings. Your Gina.”

But the note takes on a more sinister tone when its recipient is known: Adolf Hitler.

The 1935 letter is one of 300 in a new book “Briefe An Hitler” – “Letters to Hitler” – by German historian Henrik Eberle. He examined more than 20,000 letters in Russian archives.

The letters give a unique glimpse into the minds of Germans during the Nazi era, from party sycophants and ordinary citizens to political opponents and Jews suffering under the Nazi regime.

Eberle stumbled on the letters when researching an earlier book on Hitler.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“It is important to show the whole picture,” he said. “There are totally normal people’s feelings, and then there are also the thoughts of the prominent people.”

The Nazis kept meticulous records, and the letters had been carefully stored in Berlin. They were seized by the Soviet army at the end of World War II and taken to Moscow.

While some individual letters have been previously published – like one from World War I hero Gen. Erich Ludendorff complaining of diminishing freedoms under the Nazis – the vast majority have never been seen by the public.

“It was known that there was this archive, it was known it was available to be seen, but there hasn’t been a book that’s brought them all together,” Eberle said.

The 476-page book, which is being presented this week at the Frankfurt International Book Fair, is only available in German. Publishers Gustav Luebbe GmbH & Co. said there are no immediate plans for an English edition.

The letters illuminate the German zeitgeist from 1925 – the year Hitler published “Mein Kampf” detailing his ideology and ambitions – to 1945, when he ended his own life in a Berlin bunker.

Early letters were generally expressions of solidarity with the Nazi program and questions about Hitler’s views, Eberle said.

In 1925, a man named Alfred Barg, who signed the letter between two scrawled swastikas as a “deeply faithful friend,” asked how Hitler felt about alcohol consumption and whether the party would use the swastika and black white and red colors should it come to power.

“Mr. Hitler drinks no alcohol aside from a few drops during very special events and he is a nonsmoker,” Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess replied. “You should already know how we stand on the colors black-white-red and the swastika.”

The letters were primarily sorted by Hess and Albert Bormann, brother of Hitler’s confidant and private secretary Martin Bormann. They were marked with red ink if not shown to Hitler, or green ink if he had been made aware of them, Eberle said.

A few letters from people deemed dangerous – including a woman who claimed to be Hitler’s relative – were forwarded to the Gestapo for investigation.

Many went unanswered, though some drew responses that ranged from the cold and bureaucratic to the lighthearted.

The letter from 7-year-old Gina, for example, was part of a series from a Berlin family in which the parents also noted the girl wanted to marry Hitler.

Bormann responded that the letters “brought the Fuehrer true happiness.”

Between 1933, when the Nazis were elected, and 1939, the year Germany invaded Poland, the number of letters increased dramatically – and most expressed support for Hitler.

“From 1933 to 1939 it was jubilation – particularly after the (1938) annexation of Austria,” Eberle said. “There were so many letters after that you couldn’t read all of them – at least 10,000 from England, America, Austria – from around the world congratulating him.”

Some letters, albeit a minority, expressed shock at the annexation of Austria.

“After the first days of jubilation were over, we were aghast to learn that while I am eligible to vote, my wife, being stigmatized and inferior because of her Jewish heritage, must stand aside,” wrote Franz Ippich of Salzburg.

“So I decided … to ask you: Please erase the dishonorable, Jewish heritage of my wife, which is not her own fault … (by doing so) my wife’s and my offspring will become your loyal and enthusiastic followers who will bless you for all your life.”

The letter went unanswered, and Ippich fled with his wife for South America.

There were protests early on from abroad about Nazi policies; they got no response.

“Hitler was uninterested,” Eberle said. “The high point of the protests was 1934, but then I think most people realized it made no sense to protest.”

Letters sent near the war’s end showed the desperation of the German people.

“In 1945 there was a lot of advice, a lot about ‘wonder weapons’ – the people wanted to do what they could against the Allies and would make suggestions,” Eberle said.

“For example, one proposed … cannons that would shoot steel nets into the air to take down low-flying aircraft.”

By 1945, the number of letters had dwindled. Hitler got about 10,000 birthday cards in 1938, Eberle said; in 1945 he got fewer than 100.