Can a painting create music? An experiment in painting and music pushes boundaries

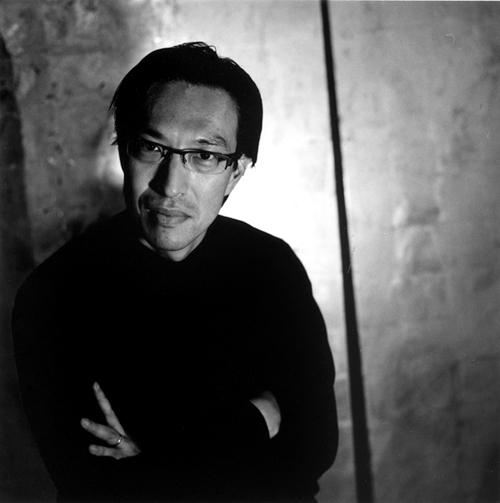

This undated photo provided by Julia Nason shows artist Makoto Fujimura, who will be premiering in an artistic collaboration with pianist Jerzy Sapieyevski at the Dillon Gallery in New York this fall, in a performance titled “Painted Music.” Julia Nason, The Associated Press

Dec 6, 2007

NEW YORK – Artist Makoto Fujimura slowly crouches then moves in stocking feet over a paper canvas spread across the floor.

He shifts his leg in front of a small black box and a rumble fills the room. He swivels again and the tone changes. Then he lowers a paintbrush that’s 4-foot high or so onto the paper and a new sound trumpets. As brush and body seem to dance, a song emerges.

From his grand piano, Jerzy Sapieyevski plays a counterpart and “Painted Music” takes shape.

Premiering at the Dillon Gallery in Chelsea this fall, “Painted Music” is a real-time exploration into “how we hear color and art,” says gallery owner Valerie Dillon.

Composer Sapieyevski has long seen the potential in combining emerging technologies with music. While the technology used in “Painted Music” may not be new, its application is intriguing.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Painting and music are natural companions. Earlier this fall, the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra enlisted two artists to stand with the orchestra and create paintings to complement the music, and Italian musician Giovanni Maria Pala recently claimed to have discovered a musical composition hidden in Leonardo’s “Last Supper.” Wassily Kandinsky famously wanted his splashes of color and line to be “heard.” Paul Klee, an accomplished musician, applied the themes and theories of music to his art.

Building on this history, Sapieyevski created a motion sensor box that is mounted above the artist’s canvas. Each space on and around the canvas corresponds to notes and styles preprogrammed by Sapieyevski. So when the artist moves his or her hand, every motion creates a sound.

The artist doesn’t create the sounds, Sapieyevski says, “I give him the notes.” But the artist creates a spontaneous composition out of those notes on the canvas. The pianist composes a response, to which the painter reacts, and the process goes back and forth.

The idea is a true dialogue: The look of the painting depends on the musician’s playing, just as the musician’s composition depends on the look of the painting.

This is a somewhat risky position for an artist. In a medium based on solitude and control, an unscripted collaboration in front of an audience takes away all the safety nets.

Luckily, Sapieyevski found a willing spirit in Fujimura, a master of traditional Japanese Nihonga painting. Literally meaning “Japanese style paintings,” Nihonga uses traditional methods and materials, typically mineral and metal based paints and silk or rice paper. Fujimura’s layered, engaging works, often on view at the Dillon Gallery, sell for between $4,000 and $150,000 and exude an easy vibrancy and calm.

Fujimura, who says he “loves to take risks, especially when it comes to broadening the language of art,” and the composer worked together for eight months, culminating in what Sapieyevski calls a “risky proposition.”

At a rehearsal in Fujimura’s studio a week before the Nov. 8 performance, the two radiated an absolutely infectious enthusiasm. Their brief sample collaborations were electric, but there was no paint and no audience.

But at the Dillon Gallery event, the collaboration was overcome by the fact that it is not easy for two masters to give up focus and control for the good of the whole. Sapieyevski bounded through his compositions and Fujimura focused intently on his painting, sometimes not triggering the musical motion sensor and not creating music. The sense of dialogue was present in flashes, but was ultimately lost.

Despite drawbacks, Dillon says that the “painting process worked beautifully.” Fujimura created three works, one of which recently sold for $45,000. And while he acknowledges that there are areas that need to be worked out, Fujimura says he is comfortable creating in front of an audience – “It’s not whether people are watching. It’s whether I feel connected to the work.”

Sapieyevski considered the evening “a big success.” Kinks? Yes, but nothing that can’t be worked through and nothing that damaged the overall feel of the performance, he says. The audience was engaged and he and Fujimura were successful in “finding each other’s atmosphere.”

Visually, there was a lot to focus on: Sapieyevski was a presence at his piano, arms and hands drifting heavenward as he leaned back and swayed to his boisterous, robust composition with an occasional, loud “Ahh.” Meanwhile, Fujimura calmly moved between his floor canvas and his easel canvas, and two large screens projected the process as it was happening, filmed by cinematographers Mott Hupfel, III and Dan Hershey.

But combining multiple disciplines does not mean they will necessarily speak to each other.

Richard Hull, an artist and professor at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has been involved in similar performances in which a time-stop video of him painting was projected with unrehearsed accompaniment by a live musician. He said that he and the musician were like “two trains on parallel tracks” meeting by chance before moving away, an observation that was played out in “Painted Music.”

People “experience music very differently than they experience visual art,” he says.

In painting, Hull says, we tend to “see the whole and then experience the parts.” In music, it is often the opposite: We hear the singer or guitar solo long before we hear the whole song. What appeals to us while looking at a painting may not have a matching counterpart in music.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that music and painting aren’t a happy couple. It means that merging the happy couple into a whole may take away the very things that made the relationship last so long.

When Fujimura created music while painting, the dialogue between the two was altered, which may or may not be a good thing. Hull “likes the idea that they are distinct, but can be experienced at the same time.” On the other hand, a collaboration such as “Painted Music” may open the door to entirely new ways of experiencing the arts, creating a changed but equally happy couple.

Dillon, Sapieyevski and Fujimura see huge, limitless technical applications, taking traditional forms to yet another level. It’s an ideology of experimentation and purpose, a merging of forms that has guidelines but no boundaries, Dillon says.

For Fujimura, it was an “honest and vulnerable” experience presented to an audience he believes is “hungering for authenticity.”