Michael Crichton dies of cancer

The Associated Press

Nov 6, 2008

NEW YORK – Michael Crichton, the million-selling author who made scientific research terrifying and irresistible in such thrillers as “Jurassic Park,” “Timeline” and “The Andromeda Strain,” has died of cancer, his family said.

Crichton died Tuesday in Los Angeles at age 66 after privately battling cancer.

“Through his books, Michael Crichton served as an inspiration to students of all ages, challenged scientists in many fields, and illuminated the mysteries of the world in a way we could all understand,” his family said in a statement.

“While the world knew him as a great storyteller that challenged our preconceived notions about the world around us – and entertained us all while doing so – his wife Sherri, daughter Taylor, family and friends knew Michael Crichton as a devoted husband, loving father and generous friend who inspired each of us to strive to see the wonders of our world through new eyes.”

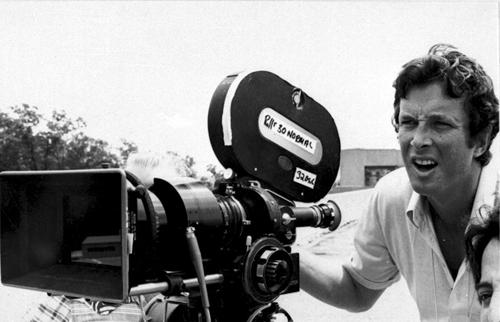

He was an experimenter and popularizer known for his stories of disaster and systematic breakdown, such as the rampant microbe of “The Andromeda Strain” or the dinosaurs running madly in “Jurassic Park.” Many of his books became major Hollywood movies, including “Jurassic Park,” “Rising Sun” and “Disclosure.” Crichton himself directed and wrote “The Great Train Robbery” and he co-wrote the script for the blockbuster “Twister.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

In 1994, he created the award-winning TV hospital series “ER.” He’s even had a dinosaur named for him, Crichton’s ankylosaur.

“Michael’s talent out-scaled even his own dinosaurs of ‘Jurassic Park,'” said “Jurassic Park” director Steven Spielberg, a friend of Crichton’s for 40 years. “He was the greatest at blending science with big theatrical concepts, which is what gave credibility to dinosaurs again walking the Earth. … Michael was a gentle soul who reserved his flamboyant side for his novels. There is no one in the wings that will ever take his place.”

John Wells, executive producer of “ER” called the author “an extraordinary man. Brilliant, funny, erudite, gracious, exceptionally inquisitive and always thoughtful.

“No lunch with Michael lasted less than three hours, and no subject was too prosaic or obscure to attract his interest. Sexual politics, medical and scientific ethics, anthropology, archaeology, economics, astronomy, astrology, quantum physics and molecular biology were all regular topics of conversation.”

Neal Baer, a physician who became an executive producer on “ER,” was a fourth-year medical student at Harvard University when Wells, a longtime friend, sent him Crichton’s script.

“I said, ‘Wow, this is like my life.’ Michael had been a medical student at Harvard in the early ’70s and I was going through the same thing about 20 years later,” said Baer.

“ER” offered a fresh take on the TV medical drama, making doctors the central focus rather than patients. In the early life of “ER,” Crichton, who hadn’t been involved in medicine for years, and Spielberg would take part in writers’ room discussions.

In recent years, Crichton was the rare novelist granted a White House meeting with President George W. Bush, perhaps because of his skepticism about global warming, which Crichton addressed in the 2004 novel, “State of Fear.” Crichton’s views were strongly condemned by environmentalists, who alleged that the author was hurting efforts to pass legislation to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide.

If not a literary giant, he was a physical one, standing 6 feet and 9 inches, and ready for battle with the press. In a 2004 interview with The Associated Press, Crichton came with a tape recorder, text books and a pile of graphs and charts as he defended “State of Fear” and his take on global warming.

“I have a lot of trouble with things that don’t seem true to me,” Crichton said at the time, his large, manicured hands gesturing to his graphs. “I’m very uncomfortable just accepting. There’s something in me that wants to pound the table and say, ‘That’s not true.'”

He spoke to few scientists about his questions, convinced that he could interpret the data himself. “If we put everything in the hands of experts and if we say that as intelligent outsiders, we are not qualified to look over the shoulder of anybody, then we’re in some kind of really weird world,” he said.

A new novel by Crichton had been tentatively scheduled to come next month, but publisher HarperCollins said the book was postponed indefinitely because of his illness.

One of four siblings, Crichton was born in Chicago and grew up in Roslyn, Long Island. His father was a journalist and young Michael spent much of his childhood writing extra papers for teachers. In third grade, he wrote a nine-page play that his father typed for him using carbon paper so the other kids would know their parts. He was tall, gangly and awkward, and used writing as a way to escape; Mark Twain and Alfred Hitchcock were his role models.

Figuring he would not be able to make a living as writer, and not good enough at basketball, he decided to become a doctor. He studied anthropology at Harvard College, and later graduated from Harvard Medical School. During medical school, he turned out books under pseudonyms. (One that the tall author used was Jeffrey Hudson, a 17th-century dwarf in the court of King Charles II of England.) He had modest success with his writing and decided to pursue it.

His first hit, “The Andromeda Strain,” was written while he was still in medical school and quickly caught on upon its 1969 release. It was a featured selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club and was sold to Universal in Hollywood for $250,000.

“A few of the teachers feel I’m wasting my time, and that in some ways I have wasted theirs,” he told The New York Times in 1969. “When I asked for a couple of days off to go to California about a movie sale, that raised an eyebrow.”

His books seemed designed to provoke debate, whether the theories of quantum physics in “Timeline,” the reverse sexual discrimination of “Disclosure” or the spectre of Japanese eminence in “Rising Sun.”

“The initial response from the (Japanese) establishment was, ‘You’re a racist,'” he told the AP. “So then, because I’m always trying to deal with data, I went on a tour talking about it and gave a very careful argument, and their response came back, ‘Well you say that but we know you’re a racist.'”

Crichton had a rigid work schedule: rising before dawn and writing from about 6 a.m. to around 3 p.m., breaking only for lunch. He enjoyed being one of the few novelists recognized in public, but he also felt limited by fame.

“Of course, the celebrity is nice. But when I go do research, it’s much more difficult now. The kind of freedom I had 10 years ago is gone,” he told the AP. “You have to have good table manners; you can’t have spaghetti hanging out of your mouth at a restaurant.”

Crichton was married five times and had one child. A private funeral is planned.