New wearable device automatically calls 911

Nov 10, 2015

“If we were, say, walking back late from some place alone, we’d call the other person and have them be on the phone with us,” Parikh said.

It’s a familiar story for many college students. Parikh and Kabaghe said they would often use apps that would allow them to call for help if they were in danger or use services like SafeWalks.

Even though they were active in ensuring their own safety, Parikh, University alumna, said she and Kabaghe weren’t satisfied with the existing technology.

“So naturally, as engineers we said to ourselves, maybe we could just do it better,” Parikh said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

They came up with an idea for a wearable device that would automatically detect if a person is in danger. This idea has since formed into their own startup company called Anansi. In an area of technology that includes numerous reactive apps allowing users to call for help with the touch of a button, Anansi is innovative in that it is proactive. It’s automatic and doesn’t require any human input to seek help.

Anansi is a bracelet-like device that monitors the user’s vital stats. If the vital stats increase beyond a preset threshold, the device vibrates. The user then has the option to cancel the alarm within seven seconds. If the alarm isn’t cancelled, it notifies 911 automatically with GPS coordinates.

Parikh said this automatic feature is crucial because, in the heat of the moment, calling for help is the last thing on a victim’s mind.

“Think about falling flat on your face . . . you know it’s happening, and you can do nothing to stop it. You know what to do to stop it, but you can’t,” she said. “The thing is, being attacked or assaulted is much like that, in that you’re very helpless in the few minutes that it happens.”

The idea for Anansi first came to life in the fall of last year when Parikh and Kabaghe took an Innovation and Engineering Design course with Scott Carney, professor of electrical and computer engineeringbr.

“(Carney) has been incredibly supportive,” Parikh said. “He’s an amazing guy. He’s a great mentor to a lot of students, and he has been to me throughout college.”

Carney encouraged them to turn their idea into a business and apply to the Chicago Innovation Exchangebr(CIE) to participate in their business incubator fellowship. The program provides entrepreneurs with resources to help them build their companies

“I thought that they would be a good fit,” Carney said. “There are a lot of resources at CIE that fit with their project.”

They were accepted to the program and spent the past summer in Chicago developing a lab bench prototype.

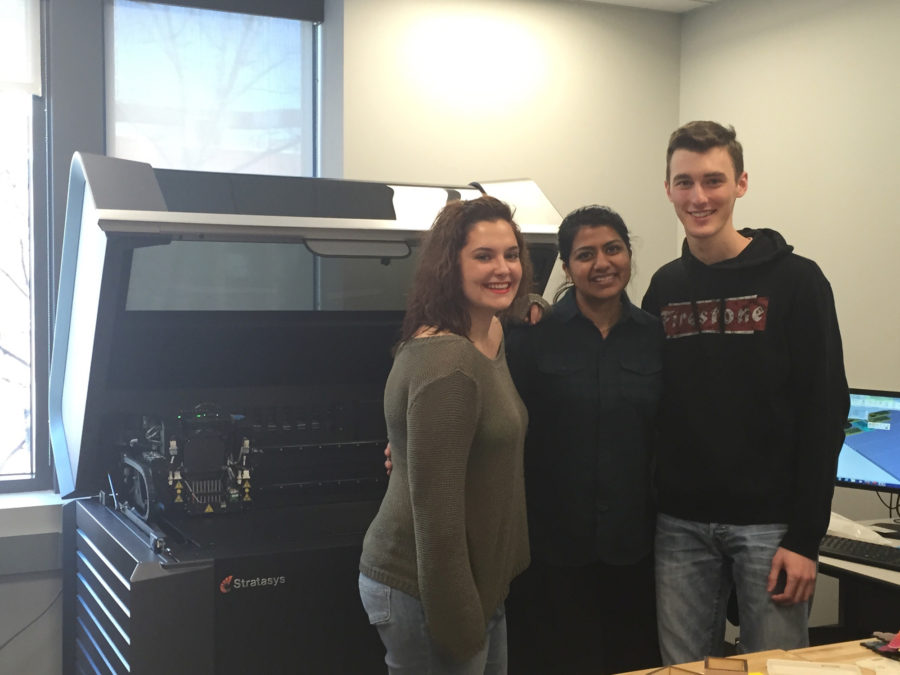

Anansi’s current team consists of Parikh and two other University alumni — Matt Vanek, a computer engineer, and Hollis Carroll, an industrial designerbr. Parikh and Vanek knew each other through college and were introduced to Carroll when she was working on her thesis project on sexual harassment.

“It was already something really similar. I was looking at making a wearable as well for my thesis project,” Carroll said. “It just kind of made sense to join them and to help them out.”

Carroll initiated the idea behind the product’s name. Parikh said Carroll brought up the fact that using their product would be a lot like having a “spidey sense.” They started looking for interesting stories involving spiders and were inspired by the story of Anansi, an African folktale character who Parikh said “protected and helped his people get out of difficult situations.”brLike the story of Anansi, their product aims to protect and help people get out of difficult situations, and specifically, their initial target market is young women. Carroll said this is why they want the device’s design to look like fine jewelry — something subtle and ideal to wear on a day-to-day basis.

The intention to appeal to women also originates in Parikh’s motivations behind developing Anansi. She said that given the recent sexual assaults that have occurred in the past few years in India, where she is from, developing Anansi mattered to her on a personal level.

“All of the women I know, including myself, have big dreams because we were brought up by our parents to dream big and to consider ourselves equal to men in every category. When I’m used to feeling equal to men in every setting, whether it’s in a classroom in engineering or whether it’s now in a startup space — it bothers me when that’s not the case when I’m on the street,” Parikh said. “This is maybe just a way to restore that balance. It’s important for people to feel safe.”

Even though there are difficulties in being an emerging startup, Parikh said it is still an exciting time for them.

“We are doing what we have to do, which is to build, build, build,” Parikh said. “We know what our steppings stones to getting where we have to be and what steps we need to take to get there.”

To receive more feedback as they continue to develop, they will also be demoing the product to University Police this month. Parikh said a college campus, specifically the University campus, would be the ideal place to demo Anansi.

The team plans to make a minimum viable product — a step-up from a lab bench prototype that has the core functions and features — ready by March 2016. Currently, they are continuing their incubation at CIE for the next six months, thanks to a sponsorship from Microsoft.

“(The sponsorship is) incredible for us, because it gives us affirmation that we’re doing okay, that this is something that is exciting, not just to us, but to other people also,” Parikh said.

Parikh, Vanek and Hollis said they believe it is the way they work together as a team — rather than how they each perform individually — that will make Anansi successful. Carney said each of their diverse life experiences and technical skills will allow them to be successful in understanding potential customer bases.

Carney said that though he’d “like to see (Parikh) running the world someday,” he would see “one life saved, one injury prevented, one crime stopped” as making Anansi a success.

Ultimately, Parikh said she sees the automatic safety concept becoming the standard down the line, even if it’s not in her lifetime.

“Maybe by the year 2300, people will be wearing this, and there’ll be this woman who’s walking down the street peacefully . . . and there’s no fear in her mind because she knows that there is no chance of being in danger,” Parikh said. “Before even an attempt is made to harm her, things will be taken care of.”