African-American Studies transforms students

Nov 30, 2016

Karen Olowu, junior in the Department of African-American Studies, has been transformed.

After joining the African-American Studies program, Olowu said she was introduced to an entirely new culture and way of thinking that she hadn’t been exposed to before.

“It’s changed me in ways I could never have imagined that it would have changed me — opened my eyes to a lot of things. It definitely opened up my eyes to a history, and a story that is often either rewritten, hidden or obscured from the dominant narrative,” Olowu said.

African-American studies at the University originated in 1969, but it wasn’t until June 2008, nearly 40 years later, that it officially became a department.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Olowu has been in the department since her freshman year and said her major has allowed her to relearn American history from a black perspective.

While she has enjoyed her experience in her major extensively, she said she thinks the program needs to be more aggressive in its outreach and should partake in more community engagement.

“African-American students, historically, at this school found the most comfort and support in the black community. Before, black students were not safe to attend the University of Illinois, and so we had very close relationships with the surrounding black community. I don’t think this department has done enough to foster that relationship that used to exist,” Olowu said.

Olowu is a member of both the African-American Studies Scholars Cultural Committee and Black Students for Revolution organizations on campus. She said these programs try to raise the political and social awareness of black students by integrating the campus with the community.

“Oftentimes we’ll try and have like a film showing in the community, open mics, volunteering at the local boys and girls club, things like that. Just showing that African-American studies is not just something you read. It’s something you do,” she said.

Given the current race relations on campus and within society as a whole, Olowu said she thinks now is the time that all the ethnic studies departments have to be aggressive in their participation in student and community education.

“I think we have the responsibility as scholars of African-American history to not just read about the struggle of black people, but actually participate in the building of black communities. We need to make sure that education (and) knowledge is easily available to our communities because knowledge is power,” she said.

Lou Turner, academic adviser and curriculum coordinator for the Department of African-American Studies, said while course enrollments have gone down, the number of students in the major and minor has increased.

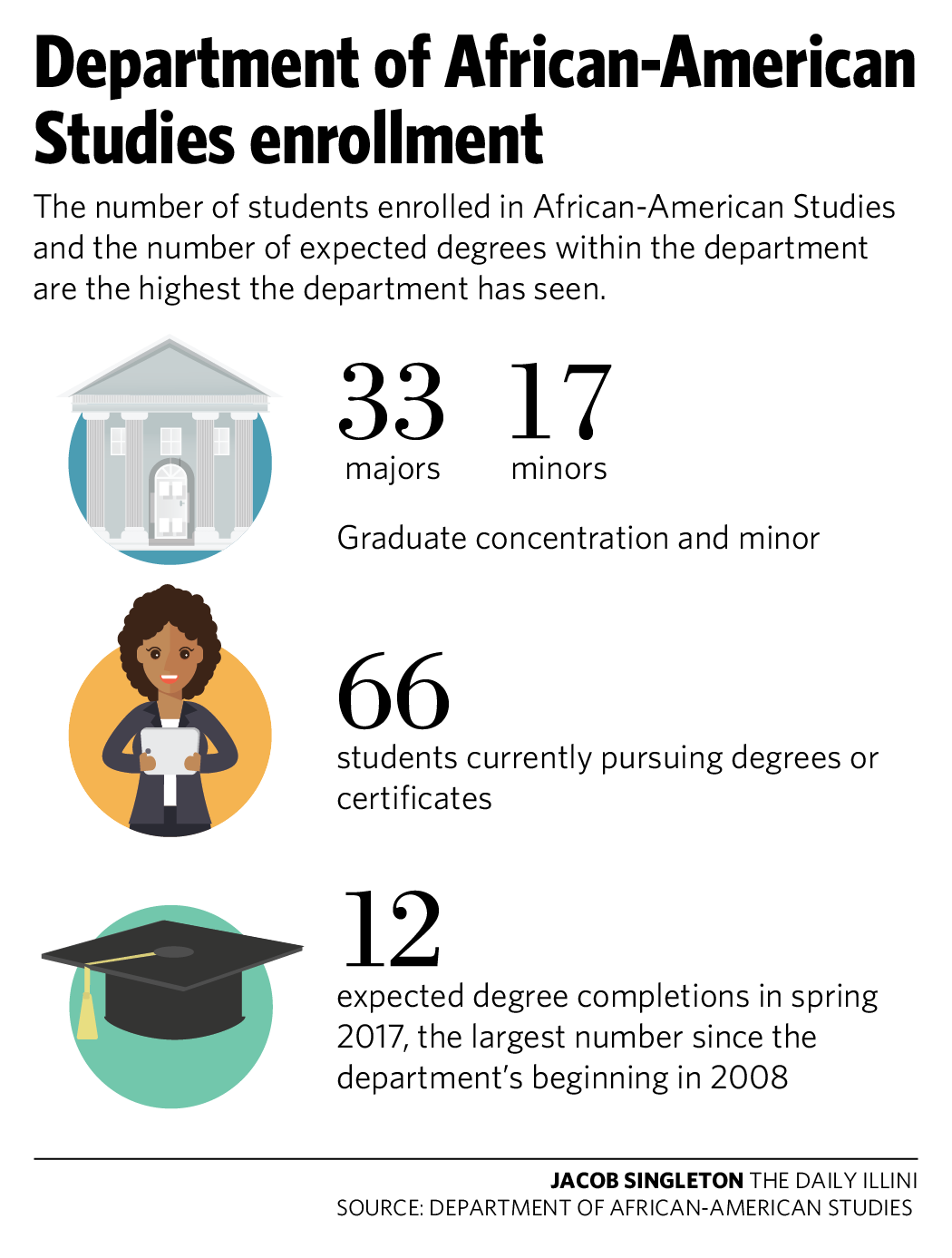

Currently, there are 33 students majoring in African-American Studies and 17 students minoring. Nine graduate concentrations and seven graduate minors make for a total of 66 students pursuing degrees or certificates in the department, Turner said.

However, the Division of Management Information states that 14 students are enrolled in African-American Studies due to students who are double majoring and are only counted for their intial major.

“We anticipate, or we are on track to have 12 degree completions in the spring of 2017, which will be the largest number of degree completions — people will be graduating with a B.A. in African American Studies — since our program started in 2008,” Turner said.

Looking at the current climate in African-American Studies, Turner said the decline in course enrollment is connected to the degree to which the department has moved away from its role as a center of discourse and debate.

Turner said the program used to be responsible for a number of conferences and forums where students and faculty could gather to speak about racial issues. He said the departments used to bring outside speakers to the campus; however, these efforts have significantly declined over the past five years.

“We had a very active profile on campus to students — Black, White, Latino, Asian, because they saw us as the department that did stuff, that responded to the events of the day, and that has to do with the fact that historically, African-American Studies is one of the few disciplines, if not the only discipline, originally that comes out of a social movement,” Turner said.

Turner said African-American Studies has always had two sides. The first involves research and the pedagogical side and the other side involves civic engagement and being involved with the community.

“When African-American Studies began to move away from that mission, then it frankly lost its credibility in the black community and began to lose, I believe, its credibility among black students,” he said.

For the department to regain its former glory, Turner said a change in leadership is what is really called for.

“If you don’t have the leadership to carry out the mission, then you really are handicapped. I think there has to be a change in the leadership of the department to get us back to the mission that we had that was very, very successful when I first came here 10 years ago. We got the team, we just need to get the leadership,” Turner said.

Shaliyah Brown, senior in the Department of African-American Studies, said she took African-American classes at DePaul University during her first two years and fell in love with the culture and history.

“I found it very fascinating and of course I connected to it; I’m a black woman. When I got here, I started exploring more of black women rights, black women history, and again, I fell in love and I just, that was my calling. This is what I’m supposed to do. I honestly believe that,” she said.

Like Olowu, Brown had nothing negative to say about the program other than its need to branch out more.

Brown said one crucial first step is the implementation of a recently approved proposal made by the Committee on Race and Ethnicity to the campus senate, detailing new graduation requirements for students entering the University in Fall 2018.

These students will need to take a non-Western culture in addition to a U.S. minority culture course as a requirement for graduation.

“I think exposure to that is really good, because I think once you get a few people in there who stay and are committed to learning more about minority studies, then it becomes bigger,” Brown said. “If you don’t have people who know about it, or who are not required to take the course, then it remains small because no one wants to take it.”

Brown said that getting to know various cultures, traditions and values is one of the most beneficial things of being in college. She said it is important for students to become educated on cultures different than their own because they interact with a very diverse group of students across campus and will continue to interact with different cultures for the rest of their lives.

Brown encouraged students to put themselves out there, not only because the Department of African-American Studies is warm and welcoming, but because all of the other minority departments located along Nevada street are as well.

“It completely changed me. I’m a completely different person because of that and I’m proud. I don’t take anything back, ever,” Brown said.

Correction: The original version of this article did not include the 9 graduate concentrations and 7 graduate minors, so the total of 66 was unclear. Further clarification about the DMI statistics has been included. The Daily Illini regrets the error.