Exhibit highlights provenance research

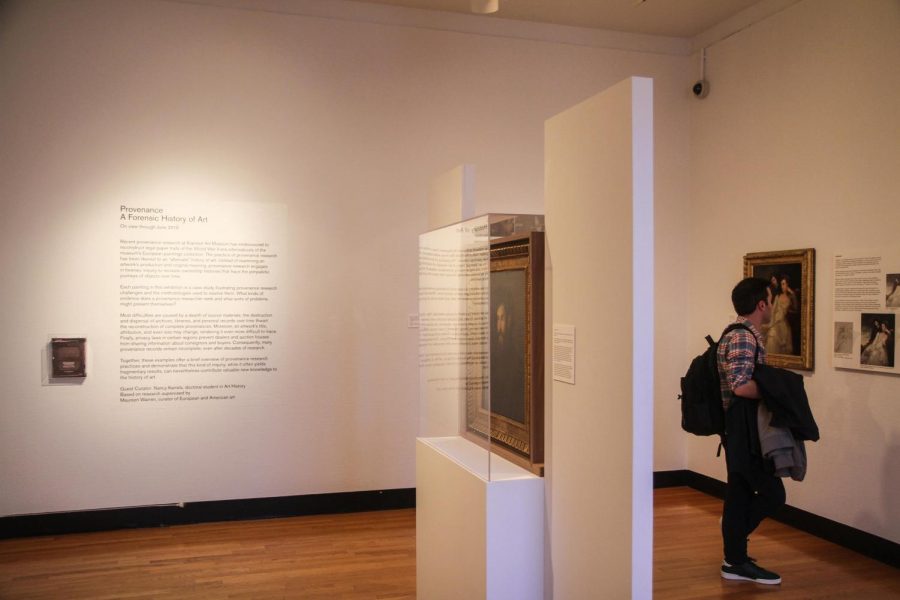

The provenance exhibit at the Krannert Art Museum. Nancy Karrels proposed the idea for a provenance research project two years ago and has been conducting research for the exhibit that opened in May of 2017.

Nov 15, 2018

About two years ago, Nancy Karrels, doctoral candidate in FAA, approached Krannert Art Museum and asked for an internship. She proposed a provenance research project.

The idea came from previous provenance work Karrels had been doing for several years. She said she wanted to keep doing that kind of research while working toward her doctorate.

Provenance research involves finding ownership histories for works of art or putting together a paper trail.

“She asked if we were interested in having her research, any works of art in our collection,” said Maureen Warren, KAM curator of European and American art. “Of course, this is really great because provenance research is really difficult, and if you don’t have a good awareness of where archives are located, if you don’t have colleagues and connections who are able to look things up for you, it’s really difficult to do.”

Karrels enrolled in independent study hours and worked with Warren to conduct her research.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

When Karrels came on board, KAM already had a gap list — a list of works of art it didn’t have complete provenance information for during the Nazi era.

“(You’re) trying to trace each successive owner of a work of art without having any gaps in between them so you can have a complete chain of ownership for a certain period,” Karrels said.

Karrels researched 27 of the museum’s paintings in the European paintings collection that she and Warren determined needed additional World War II provenance research.

Warren said Karrels worked close to 500 hours on the project after two years of research. Karrels established legal chains of ownership on the pieces, proving they weren’t stolen or looted at any point in time.

When she finished researching, Karrels and Warren realized although the results looked small on paper, the findings told many stories that couldn’t be captured in a list of names of previous owners.

From there, Warren and Karrels decided to do an exhibition to share those stories. After they came up with the idea, Karrels said it developed very organically due to the knowledge of Warren and the rest of the KAM staff.

“(Warren) was really an excellent mentor and an excellent guide and supervisor in this process,” Karrels said. “She really knows how the museum runs, how to put on a good exhibition, what was needed both in terms of the art historical research, but also in terms of the planning for how to select artworks for the exhibition, how to arrange them, what kinds of information people would be interested in learning about.”

Jon Seydl, KAM director, said this kind of exhibition is rare. He said he doesn’t think many people realize how complicated provenance research is.

“The stories … sometimes they’re neat and tidy,” Seydl said. “But a lot of times, there’s really, there’s all kinds of ambiguities; there’s a lot of things that need to be teased out; there’s dead ends; there’s hidden surprises. And I thought Nancy’s exhibition really brought out each of those types of stories.”

The exhibition has been open since May 2017 and runs through Dec. 8.

Warren said provenance exhibits are fairly limited. Many times, she said, they focus on research outcomes. This exhibit focuses on the methodology.

One of the works is displayed so viewers can see the front and back. The back of the painting has an Austrian export stamp.

Many times when goods are moving through a country, and the country has given permission for an object to be sold, it will get an export stamp.

This particular Austrian export stamp was used by the government for four months after the Nazis took control. Some looted artwork left the country with that stamp.

“Her exhibition explains how we haven’t been able to track down exactly when this painting left Austria,” Warren said. “So we don’t know for sure that it was in that four-month window, but we know it was possible. So it becomes what researchers sometimes call a red flag. It’s not proof that the object was stolen or looted, but it’s a sign that we want to look closer.”

Provenance research is difficult, Warren said, because there are a lot of dead ends.

Karrels said every painting you do provenance research on is completely different, because of previous research and available information. Every case is different, she said, which is why provenance research takes so long to complete.

A difficult truth, Karrels said, is much information is never available. Many records get lost over time.

During her research, Karrels was looking for receipts for works of art transferred 100 years ago. Often when doing this kind of research, she said she doesn’t find the smoking gun, so she has to go about it in different ways.

“I look for any trace of ownership that can be found in legal documents like wills and testaments; any items that might have been put for sale at auctions where we can learn who the seller was or who the buyer was or ideally both,” Karrels said. “And also researching previous provenance research done on an object and taking those sources to try to lead it back to documents as often as possible.”

Karrels’ exhibition is one of a small number of provenance exhibits. When they were planning it, it was something completely new. Now, other provenance exhibits are in the works.

“We’re on the vanguard of this new effort to bring attention to provenance research as an integral part of museum work and art history,” Karrels said. “That’s been a new development that has been really interesting and gratifying to me as a provenance researcher.”