New commission to improve Illinois crime labs

Sep 23, 2022

A group of scientists, lawyers, Illinois State Police leaders and victim advocates want to change the state’s forensic crime labs to better serve communities.

Known as the Illinois Forensic Science Commission, the commission wants to address issues like staff shortages, how to better handle evidence from sexual assault cases and the ethics of DNA databases.

“How do we make sure that (cases) can move through the system so that ultimately, people who commit crimes are held accountable for it?” said Carrie Ward, a victim advocate on the commission and executive director of the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

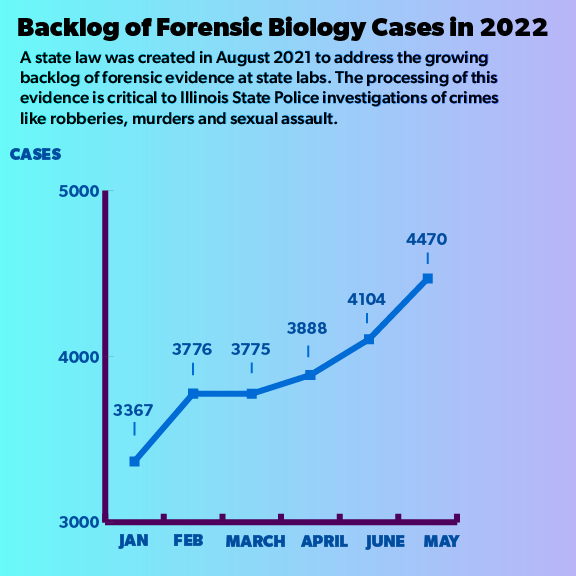

The commission began meeting this past March at the University’s Carle R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. One of its main goals is to reduce the backlog of forensic cases in labs across the state, which happens when the number of cases is greater than what the lab staff can process at a time.

According to a report from the Illinois State Police in July, the backlog for fiscal year 2022 was about 4,500 cases. These cases require DNA analysis and use more resources than others like toxicology reports or firearms analysis.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Although this is a 24% increase from the previous year, there were more submissions and also new procedures. As of Aug. 31, there were about 5,200 cases in the backlog.

Cris Hughes, clinical associate professor in LAS, is the only academic representative on the commission. She’s also the deputy forensic anthropologist for the Champaign County coroner’s office, working with human DNA to help in cases involving unidentified persons.

“DNA can often be one of the major sources of evidence to produce a positive identification,” Hughes said. “Delays in the evidence mean a delay in identifying the individual, leaving loved ones waiting to know what happened.”

The commission is also interested in how to tackle ethical issues concerning DNA privacy. These days, it’s possible to track down a murder suspect through a distant relative that used an ancestry testing service, for example.

Hughes said this approach has to be looked at from all angles — genomic privacy, public opinion and existing inequities are all discussed by the commission.

“Honestly, there’s so much work to be done and I’m excited that our state has implemented the commission to assist, and I am proud to be a part of it,” Hughes said.

Gov. JB Pritzker signed the commission into law in August 2021. Prior to this, the state’s Forensic Science Task Force reduced the state backlog by 33% and recommended that a permanent group be created to further improve the system.

Ward, who is on the commission currently, also served on the task force. As an advocate for survivors of sexual assault, she said her perspective can be different from law enforcement or scientists.

Sexual assault is different from robbery or murder in that it continues to affect someone’s bodily autonomy, Ward said.

“For survivors who have to wait a long time after they’ve already come forward with the experience of sexual violence, and then perhaps be given incomplete or uninformed answers about the status of their case — it is doubly traumatizing,” Ward said.

The diverse array of experts involved makes this commission different from other groups Ward has been a part of, she said.

“We just wanted to make sure that we don’t, as a part of any system, do things that further harm survivors as opposed to helping them,” Ward said.

The commission will meet four times a year at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. Subcommittees on public policy, career development and technology also meet throughout the year.

Gene Robinson, director of the IGB, said that society is in the middle of a “genomics revolution,” which requires careful consideration of how scientists can gain the trust of the public as well as fix past mistakes.

“Genetics can be used in terrible ways and have been used in terrible ways to create inequities and to create horrible situations,” Robinson said. “If you’re working in this field, one has to be aware of the past, and then use that to create a better future.”

Robinson said the commission is bringing science to society by working with scientists, policymakers and researchers at the University.

“Genomics has increasingly been playing a role in both sides of the equation — guilt and innocence — and technologies are getting better all the time,” Robinson said. “The criminal justice system is a system that everyone wants to see improved equity in.”