UI Student wins national change ringing award

Dec 6, 2022

The sound of bells rings out from Mitchell Tower at the University of Chicago. There is no discernible melody, but the bells chime without stopping, one after another, without repeating a single note or pattern twice in a row. They are demonstrating an art form roughly 400 years old — the art of change ringing.

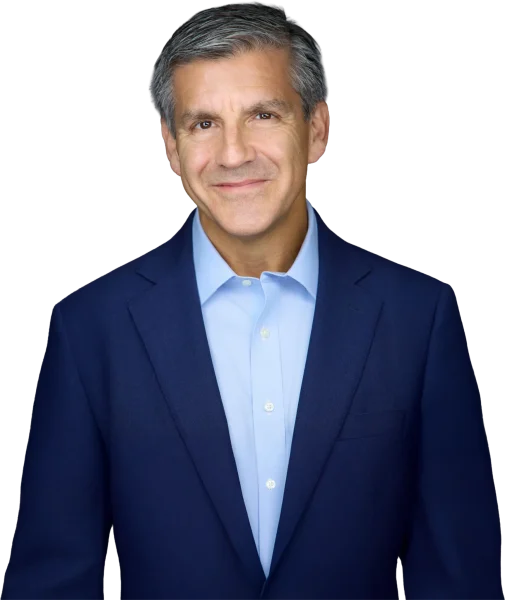

One ringer at the tower is Sean Lu, sophomore in DGS, who has been honored with this year’s Jeff Smith Memorial Young Ringer Award from the North American Guild of Change Ringers.

Change ringing is an art where towers’ bells are rung in different sequences instead of according to traditional musical notation. As the name “change ringing” implies, those sequences change after each bell is rung, with the next sequence predetermined by switching the order of two bells rung in the previous sequence. What results is not a melody but rather an auditory exploration of mathematical sequences.

Lu discovered change ringing in early 2021 after stumbling upon a YouTube video. He was immediately drawn to the art as it lay at the intersection of math and music. As a self-proclaimed “math nerd,” Lu also played the upright bass in high school and saw change ringing as the perfect combination of his two interests.

“It’s more like solving a puzzle and getting satisfaction from that rather than any particular musical result,” Lu said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

For some ringers, the ultimate goal is to ring every permutation possible on a tower’s set of bells, playing every possible ordinal combination without repetition. This feat is called a peal and is most commonly attempted on seven bells. This requires at least 5040 permutations and usually takes a group of ringers three hours to complete.

A slightly less intense feat is called a quarter peal and requires 1260 permutations, a quarter of a full peal’s amount. Still impressive in its own right, a quarter peal takes roughly 45 minutes to complete. Lu has completed four quarter peals in his time as a ringer thus far.

Lu rings at Chicago’s Mitchell Tower while at home in Naperville. While at the University, he practices by using handbells, which he keeps wrapped in white gym socks for protection. Lu, his brother and usually a few friends set up in front of the Union on Sundays to practice on Lu’s set of handbells.

Tom Farthing, a Chicago-area change ringer and press secretary for the NAGCR, nominated Lu for the award after ringing with him for the past year and a half.

“He is a sponge,” Farthing said. “(Change ringing) takes a lot of learning to do, and whenever we present him with a new concept, he just gets it right away and incorporates that. It’s a lot of fun for the people who are teaching him.”

Jeff Smith, the namesake of the award, was a mathematics professor at Kalamazoo College who taught hundreds of students the art of change ringing. Farthing, who instituted the award to honor college-aged ringers and promote the growth of change ringing in North America, was taught by Smith himself.

Change ringing originated in England and still has ties to the anglophone world as it is still practiced in many areas of the former British empire. Although it remains far more popular in England, a dedicated and close community has formed in North America. Since the demographic skews toward older generations, Lu has come to appreciate the variety of people he’s met through ringing.

“It’s a mix between older and younger people, and I think that’s a good thing because the older people can bring interesting conversation,” Lu said. “When I go to school, I feel like I’m surrounded by only one age group, but with change ringing, I get to meet a bunch of older people, not just as teachers or mentors, but just as peers.”

Those involved with change ringing say that a special type of bond forms between those who ring together. Ringing is unique in that individuals work solitarily on their own assigned bell to achieve a collective goal. Quilla Roth, a ringer from Washington D.C. and education officer for the NAGCR, said that there is a unique social aspect to change ringing.

“While you’re ringing, you’re not talking or touching anyone the way you would when you dance, and yet there’s a kind of intimacy,” Roth said. “It’s similar to the kind of intimacy I observe in string quartets where the players are very attuned to each other. We spend a lot of time not talking to each other — ringing — but then we go off and have social time with a meal or ‘going to the pub,’ as they say in England.”

Despite the tight-knit community that can come from ringing, some ringers have discussed the difficulty in getting younger people into change ringing. Eileen Butler, a Philadelphia area ringer and president of the NAGCR, emphasized the need to reach youths to proliferate ringing in North America.

“We really need to get more youths into change ringing,” Butler said. “It’s very hard to get young people to commit to that kind of time commitment because learning how to (ring) can be the most time-consuming part.”

Still, Butler attests that learning about the world of change ringing can open doors and form communities around the world.

“Anywhere you go where there are bells, you’ll walk in, and they’ll ask, ‘Are you a ringer?’” Butler said. “If you say yes, they’ll say, ‘Well, you’re welcome here!’”