An interest in mathematics began at a young age for Melkior Ornik, professor in Engineering. Ornik participated in math competitions as early as the fourth grade, an extracurricular which culminated in representing his country in the 2008 International Mathematical Olympiad.

In that particular year, it was a title that just five other Croatians and 534 people could boast worldwide. Ornik scored bronze in the two-day, six-question event, and it only seemed natural to continue his mathematical studies at university.

His journey in higher education began at the University of Zagreb with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. Despite his highly applied area of focus in the present, a future in theoretical mathematics was what Ornik envisioned at the time.

“When I started doing my original math degree in undergrad I was convinced that I was going to be a pure mathematician,” Ornik said. “Work on real analysis or functional analysis or whatever it is and just do straight-up pen and paper work entirely. Over time I think I realized, similar to my feelings about chess, I have a lot of respect for people who have the patience for it … I just like to see something moving. So I started kind of moving a little bit towards applied math.”

Although never feeling a conscious need to flee the coop, Ornik’s next academic stop was quite far from home. He received his master’s degree in mathematics at Queen’s University Canada, before completing a doctorate in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Toronto. During those years in the Great White North, his budding interest in applied mathematics came to a head.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“When I went to Queen’s I was still in the math department,” Ornik explained. “But the math department at Queen’s includes both pretty pure people and pretty applied people, I was on the applied side. I was working on controls and this was the first time I was actually working on controls.”

A decade after the beginning of Ornik’s graduate education, control engineering is still the focus. Both in the classroom and in his research, designing controllers that drive systems to desired states is at the heart of it all.

Ornik made his professional leap to the United States as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin after applying to a plethora of universities. He was unsure about shooting for faculty level so soon, but just a few months into his tenure at Texas and after some convincing from his advisor, the application process restarted.

“When I visited aerospace here, ECE as well, and saw everyone I really felt at home,” Ornik said. “The aerospace department is very welcoming. I felt like it was going forward, it wasn’t stagnating and I really liked the environment. When they made me an offer I said yes and I didn’t regret it for a single minute.”

The draw to being an instructor is deeply rooted for Ornik, who describes his life as a never-ending pursuit of knowledge and the opportunity to pass that knowledge on to others as an ultimate form of satisfaction.

“I am a person who constantly wants to gather more information,” Ornik said. “I think that kind of colors a lot of aspects of my life. I travel a lot, I’ve been to 40 countries and I think a part of that is driven by me trying to get as much information about the world as possible.

“The opportunity to share this knowledge with people in the hope that there’s maybe some other people out there who also want to learn about things and who want to get smarter, that’s what really drives it for me.”

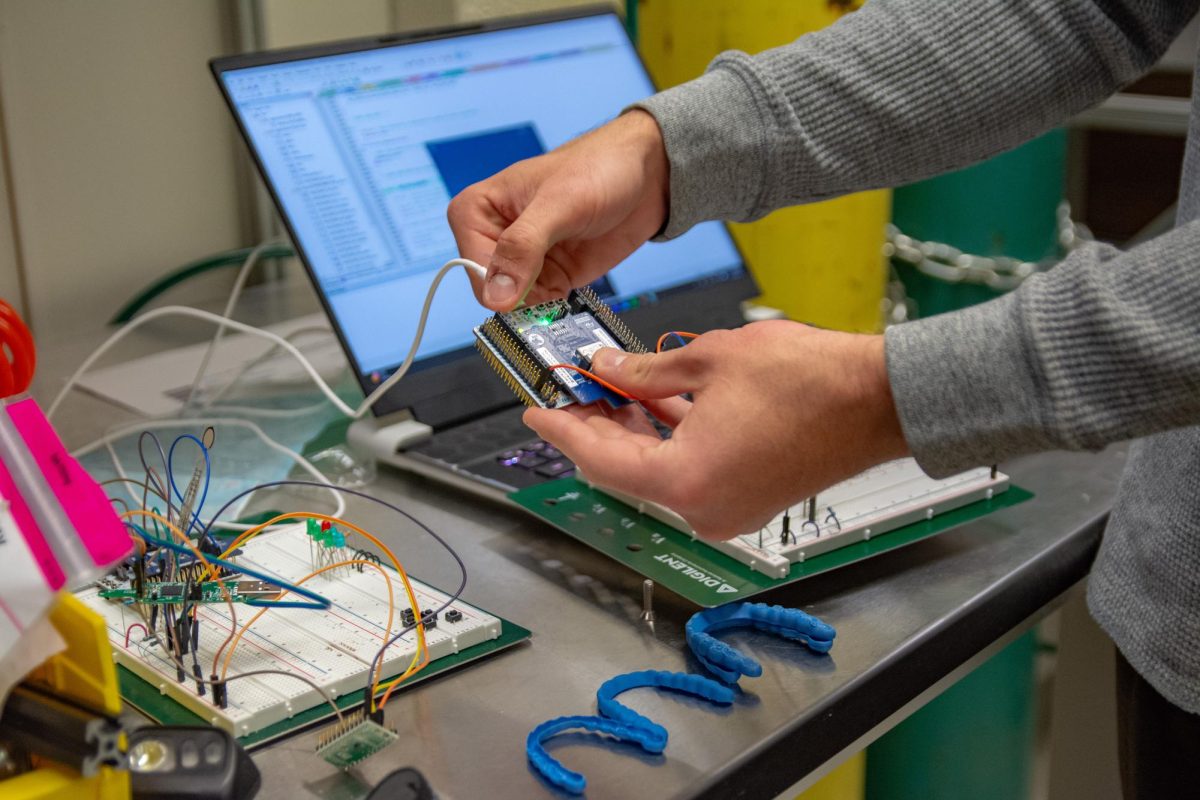

Consisting of 15 total undergraduate, graduate and postdoctoral researchers, Ornik spearheads LEADCAT: LEArning, Decision, Control, AuTonomy. Ornik described his research group as one of the least experimental in the department.

Ornik said that it’s through collaboration with other groups that LEADCAT is able to achieve the more material results that drove him to control in the first place.

“We have a great project on robotic manipulation of surfaces of granular media,” Ornik described. “One of my students is actually working with an actual robotic scoop and this is a collaboration with professor Kris Heuser in computer science. Our pieces fit into these bigger stories, usually our piece is that we try to make it a theoretical engine for a lot of the applied work that’s going on.”

It’s because of this that Ornik is hesitant to claim the potential big-picture rewards that his completed research would yield. He has an incredible amount of respect for those who help bring his group’s theory to life.

“I don’t want to pretend that this is all my work and that if I just completed everything I am working on, all of that will magically work out,” Ornik said. “In the grand scheme of things, it takes a village. It takes the people who know things that I don’t know anything about. Like, c’mon, I have no idea how to construct a robot.”