The Laboratory for Optical Physics and Engineering sits in the heart of the University’s campus in Urbana. Many students walk past the building every day and may be unaware of the fact that, on the second floor of the lab, a coalition of dedicated student engineers is chasing history.

This is Liquid Rocketry at Illinois, a registered student organization that has fixed its gaze on exploits no college team has ever accomplished.

“The overarching long-term goal is to ideally be the first collegiate team to launch a liquid-powered rocket to space,” said Demir Can Erkiralp, sophomore in Engineering and the club’s president.

To etch their names in the history books, LRI would have to propel a flight vehicle above the Kármán line — the legally agreed upon boundary of the atmosphere and the periphery of space, some 330,000 feet above sea level.

While the University of Southern California’s Rocket Propulsion Laboratory became the first undergraduate group to reach space back in 2019, they did so using a rocket powered by solid fuel. Liquid rocketry, the discipline practiced by LRI, provides its own unique set of challenges.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“It’s a very difficult, expensive and somewhat advanced form of rocketry,” said Colin Reedy, sophomore in Engineering and leader of the club’s pumps team, one of six specialized units on the LRI roster.

All rockets require two major components to function: fuel to power the rocket and oxygen to oxidize the fuel. Unlike atmospheric vehicles, rockets must store and use oxygen, as there is no oxygen in space.

The main distinction between solid-powered rockets and liquid rocketry is that in solid rockets, the fuel and oxygen are in solid form and are already mixed. In liquid rocketry, the liquid fuel and oxygen are stored in different tanks and must be siphoned into the combustion chamber at an extremely precise ratio for the rocket to function.

While this process increases the efficiency of the rocket, one slight miscalculation or malfunction in liquid rocketry can have catastrophic consequences.

“A solid rocket engine wants to fire until it’s out of fuel and out of propellant and just stops burning,” Erkiralp said. “A liquid rocket engine at every point at every step of the way wants to violently explode.”

While the task of launching the engineering equivalent of an explosive with an upset stomach over 62 miles into the air seems almost impossible, LRI’s willingness to go the extra mile is giving them a leg up in this rehashed version of the space race — specifically by their use of pumps.

“Pumps you can essentially think of as a turbocharger in a car,” Reedy said. “The way a car works, you can turbocharge a car, make its engine run faster. You can turbocharge, or pump feed, an engine and make it run faster or effectively stronger — you get more thrust out of it for the given engine size.”

Pumps execute this function by adding pressure, which pushes the fuel and oxygen necessary in liquid rocketry together. Shoving the two propellants upon each other provides more force compared to the typical pressure-fed engines.

While pressure-fed engines are more convenient when building on a smaller scale — and thus more popular among collegiate rocketry teams — the rockets constructed by NASA and other forerunners in rocketry are all pump-fed.

It’s an added challenge, but one LRI believed is worthwhile in both the short and long term, helping the club’s current projects become lighter and more efficient while also preparing LRI’s members for their eventual career goals.

“Because fluids always go from high pressure to low pressure, you need to somehow have higher pressure than the inside of a rocket engine,” Erkiralp said. “You can either do that by having very thick tanks that hold a lot of pressure or you can have very thin tanks and have a pump that provides you with that pressure instead.

“The reason it’s groundbreaking is because we’re one of the first collegiate teams that won’t need to have very thick tanks.”

Not only will these thinner, more efficient engines aid the crew in their projects, but the understanding of pumps will help them master the cutting-edge technologies of modern liquid rocketry, contributing towards a smoother transition into the field after college.

“It’s a lot of added complexity, but for the nature of the way rocketry works in the long term, it will be a lot more high performance and will enable us to make bigger leaps in the future,” Reedy said.

With LRI emerging at the forefront of collegiate rocketry innovation, it may be easy to forget the club’s core members are still working on their undergraduate education, learning the disciplines they seek to apply. As a result, the group is pooling their knowledge while expanding each other’s capacities in pursuit of their lofty goals.

“It’s basically up to us to teach ourselves this year about the fundamentals, and then at the same time, try to teach new members these fundamentals,” said Santiago Zapata Zuluaga, sophomore in Engineering, who leads the engine team.

While the team seeks to spread as much information as possible, members said the idea of getting every one of the club’s members to the same standard of knowledge while also working towards the club’s practical aims is not easy. As a result, LRI is taking a divide-and-conquer approach to tackling the vast expanses of rocketry know-how.

“Everyone kind of develops their own area of knowledge and expertise,” Reedy said.

LRI said they are also facing the difficulties of trying to gain relevant information from the professionals.

In a field known for the cutthroat nature of its private sector as well as heavy regulation due to the similarities between rockets and destructive weapons like missiles, the precious nuggets of information that sift through to collegiate teams are few and far between.

“Nobody is going to be selling defense technology to a bunch of college students,” Erkiralp quipped.

For the most part, the only unregulated information available to teams like LRI is buried deep in the annals of engineering history, with the most recent unobscured information dating back to the 1960s.

This data has become slightly outdated in the grand scheme of rocketry, as the field has made a seismic shift from its trial-and-error nature back in those days to becoming heavily analytics-driven and engineering-focused.

“We have to do the engineering ourselves,” Erkiralp said. “We don’t have a precedent that we can essentially refer to in a textbook and be like, ‘Okay, yeah, that makes sense.’”

LRI can’t just model their work after existing blueprints, but they still have an important pipeline to get them on the right track: connections.

The club’s founding pair, University alumni Ian Brown and Bartosz Wielgos, work at Elon Musk’s renowned company SpaceX, and the club has a wide range of ties throughout the aerospace industry.

To make the complicated mechanics of LRI work, the group’s internal network is substantial. The organization has experienced an increase in members from its inception under Brown and Wielgos to the fusion of two separate clubs, the Liquid Rocketry Initiative and the Turbo Machinery Initiative.

The RSO of roughly 50 students is strategically split into specialized teams, each of which is tasked with tackling a different area of liquid rocketry.

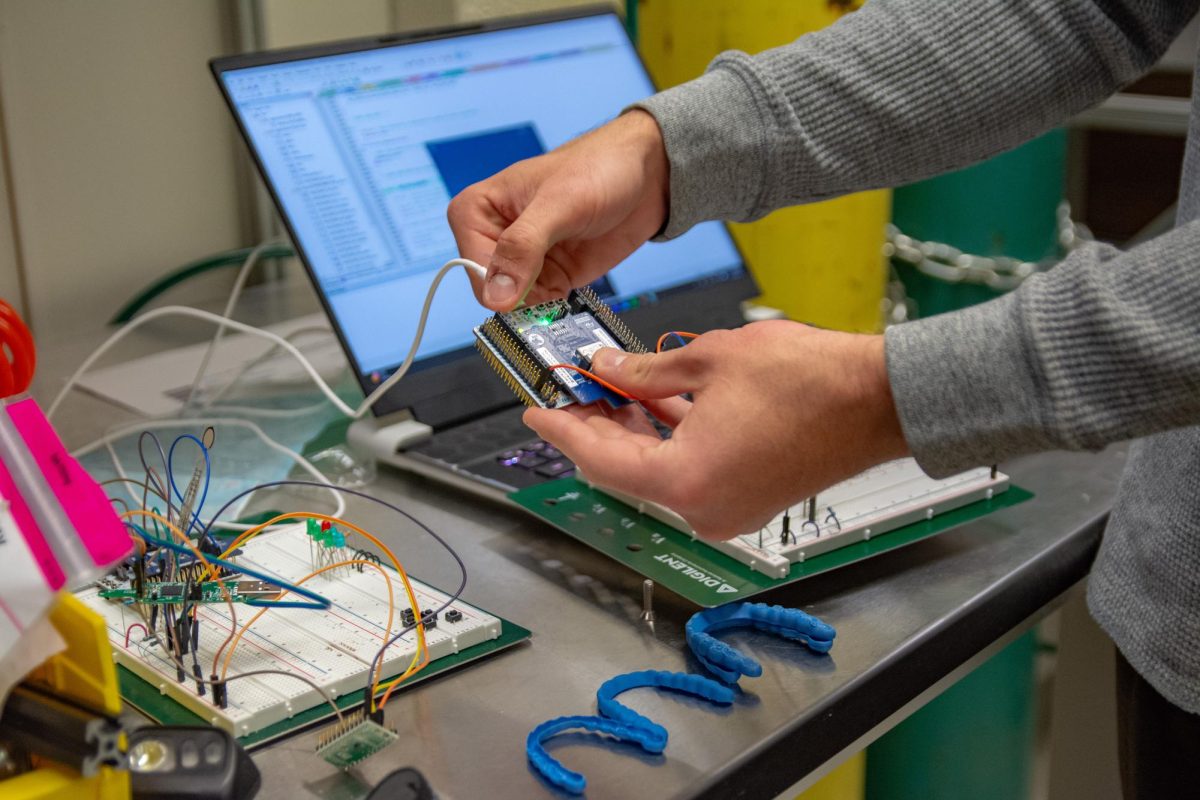

The club consists of the engine team, the pumps team, the electronics team, the testing team, the simulations team and the flight vehicle team.

At the moment, this specialized yet harmonious conglomerate is working on several projects, including a brand-new test stand and engine. The test stand, the second such stand erected by LRI, is an invaluable resource for the club’s testing and information-gathering endeavors.

“You can build rocket engines all you want, but you cannot learn anything from them, or at least nothing valuable enough, if you cannot test them,” Zapata Zuluaga said. “So that’s what we’re building right here.”

The current test stand LRI is working on represents a marked improvement over their first attempt. The club took what they learned from the initial prototype to create its smaller, more efficient and more portable successor, which should be the bedrock of several of their future projects.

Additionally, LRI is working on its second student-designed rocket engine, a liquid methane-powered behemoth known as Unity. A test-firing of the first student-made engine, Grunt, is scheduled early in the 2024 Spring semester. The operation marked the first-ever rocket firing by a University of Illinois collegiate team.

“I think it’s important to emphasize just how big of a challenge this is,” Reedy said. “If you look back in the history of some of these very famous space companies, some of the early ones from the ’60s, it took years for those initial developments to really get them anywhere past that Karman line or even for their orbit … A bunch of college students trying to accomplish a similar goal — that is a level of dedication and time that takes a lot of people, it takes a lot of effort and it’s a very big challenge.”

Members said liquid rocketry is an expensive discipline. If you’d like to financially support LRI, go to its GoFundMe.

LRI is looking to add members with a passion for liquid rocketry regardless of major and is actively looking for more sponsors. To reach out about joining or sponsorship opportunities, contact [email protected].