As freshmen enter the University of Illinois’ campus grounds for the first time, it can be exciting for many, but also nerve-wracking trying to find where one belongs in the institution.

It has been observed that much of students’ academic success in college relies on an individual’s sense of belonging; without belonging, students are more likely to feel less motivated in school. Because of the importance of belongingness in a college environment, it has become a growing field in educational psychology.

In an email interview, Amir Maghsoodi, graduate student studying counseling psychology, explained the meaning behind college belongingness is very nuanced.

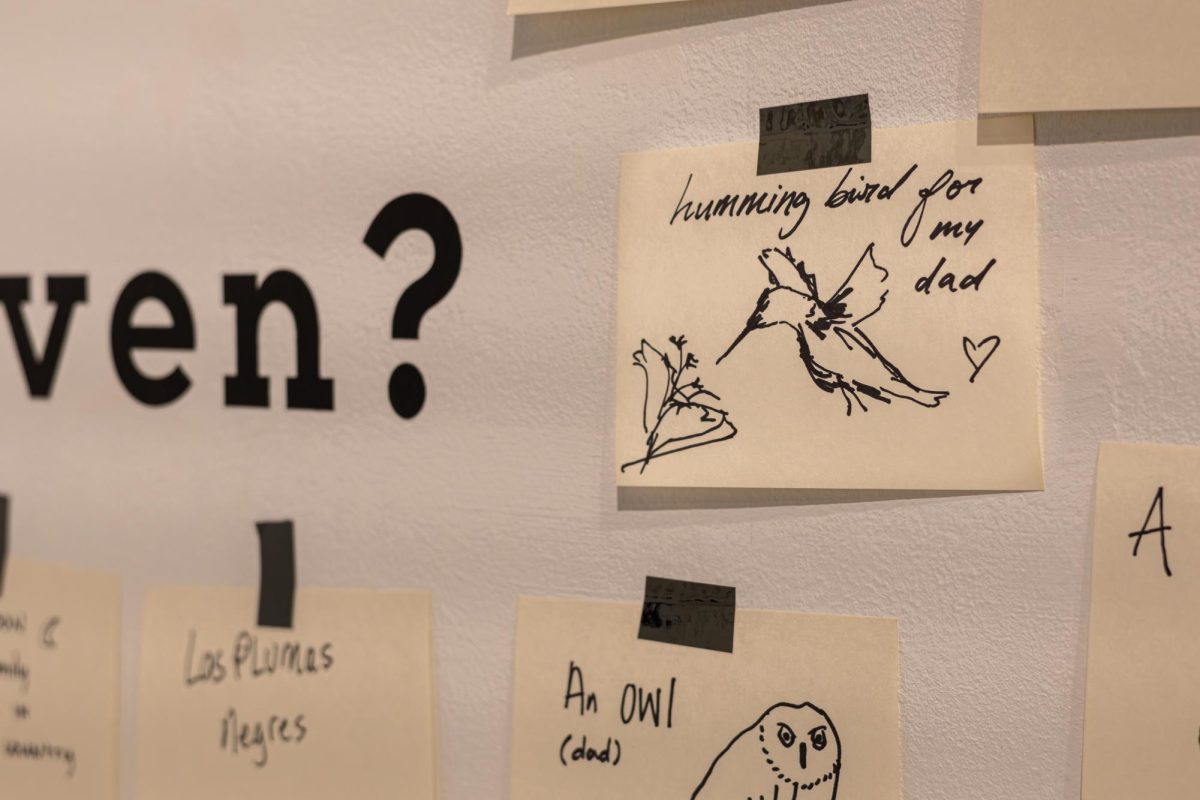

“We are still understanding the depth and nuances of all that is encompassed within the idea of ‘college belongingness’ for students,” Maghsoodi said. “I think some important aspects of college belongingness include feeling seen, respected, valued and supported as a member of the college community. Feeling like one knows how to navigate the college academic system and having a felt sense of connection to the college and members of the college community.”

One of the most famous college belonging tests was developed by social psychologists Gregory Walyon and Geoff Cohen in 2007 called the Sense of Social Fit Scale.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The SSF scale is a test with 17 items that measure how much a person feels they belong on their college campus. People taking the test would read a sentence and answer how much they agree or disagree with the statement. These statements include “People at (school name) accept me,” or “I feel like an outsider at (school name).”

As Maghsoodi was developing his Master’s thesis, he wanted to use the SSF scale to see if there was a relationship between a sense of belonging and perceived stress on college campuses. However, he realized there were certain issues with the scale.

“I realized that my data did not align with how the scale is typically viewed, which is as just a single-factor scale of belonging,” Maghsoodi said.

The SSF was considered to be a single-factor scale, which implied its questions only focused on one aspect of belongingness. However, since his data conflicted with this idea, there’s a chance there might be multiple factors that influence college belongingness.

Nidia Ruedas-Garcia, assistant professor in Education, advised Maghsoodi in his research, discovering that no one had tested the scale’s reliability and what its factor structure was.

“We kind of asked each other, ‘So what has been the validity of this scale? Like, what is the factor structure?,’” Ruedas-Garcia said. “In other words, do we put all of these questions together and take the average and that sense of belonging, or do we take four questions? Then we realized, ‘Oh, there hasnʼt actually been a study that has told us how to do this and how to score this scale.’”

As a result, Maghsoodi shifted the focus of his masterʼs thesis to research the scale’s factor structure and its reliability, making this the first study to systematically investigate SSF.

The research team conducted two studies where they sent the SSF survey to two predominantly white institutions. The first study garnered 243 respondents in one institution in the West and the second received a larger sample size of 413 students in another.

After analyzing the data results, the research team concluded the SSF scale was reliable.

“I thought that was cool because we didn’t know that for,” Ruedas-Garcia said. “We just assumed that it was valid and reliable. You can put all 17 items slash questions together, take an average score and youʼll get a general sense of how much a student feels like they belong.”

They had also identified four factors that influenced college belongingness. These four factors involve identification with the university, social match, feeling of social acceptance from people on campus and cultural capital.

According to Maghsoodi, cultural capital refers to the people in our lives who give individuals the skills and knowledge to help navigate various aspects of their lives. In a college setting, these could be parents or mentors who have experienced what college is like.

Ruedas-Garcia finds cultural capital fascinating due to how some students might not even realize they have it and how much it influences their college experience.

“The reason why (cultural capital) excites me so much is that I think it is something that people benefit from and it can be hard to notice when you’re benefiting from it,” Ruedes-Garcia said. “If you come in and both of your parents went to college, your parents will probably know exactly what a dorm looks like and what to buy you for your dorm. They will probably work with you on which major to pick and which classes to take.”

As a result, having cultural capital can make navigating college easier, which can increase the likelihood of achieving academic success. However, not all undergraduate students have guidance from parents or mentors who have gone to college.

According to the Higher Education Act of 1965 and 1998, first-generation college students are defined as students whose parents did not receive or complete their college degree. In 2016, 24% of 7.3 million undergraduate students were first-generation, half of whom come from low-income families.

As a first-generation college student, Ruedes-Garcia had a hard time adjusting to college life as a former undergraduate student at the University of California Los Angeles.

“Throughout my undergraduate studies, I often felt like I didn’t belong for many reasons, including not knowing how to navigate college, not knowing who to talk to or how to talk to them when I needed help and then not seeing people like me, represented as faculty or in the student population,” Ruedes-Garcia said.

However, Ruedes-Garcia said she was able to acquire cultural capital through her university’s encouraging faculty and programs that supported first-generation students.

During her time at UCLA, Patricia Greenfield, a psychologist, took Ruedes-Garcia under her wing and provided her the direction and mentorship she needed, inspiring her to delve into researching college belonging.

Ruedes-Garcia explained the importance of having a support network in college, especially having a mentor.

“You have people that sit you down and say, ‘Hey, you’re doing amazing, sweetheart,’ Or just in general, ‘You’re doing amazing, kids,’” Ruedes-Garcia said. “I think that that really boosts your esteem and your confidence in the work that youʼre doing, and it boosts your sense of belonging. Because you feel value and you feel like you matter. You feel like someoneʼs looking for you or thinking of you.”

However, college students lacking cultural capital still persist. According to the teamʼs research, they found white students in PWIs tend to score higher than Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders on cultural capital.

“PWIs have long been structured to primarily serve white students,” Maghsoodi said. “Despite reforms, these structures still tend to privilege the cultural capital of white students.”

Ruedes-Garcia explained this trend could also be because the culture of college tends to be a new environment that clashes with how some people are raised.

“When they step into college, the practices and traditions, the culture of college may be different from how they grew up and how they were raised,” Ruedes-Garcia. “So there’s more of a mismatch.”

Despite these issues, Ruedes-Garcia says there are many ways universities can help students achieve more cultural capital.

“Thereʼs a lot of ways that we can build cultural capital and not only by teaching these students the ways of college, but also for the institution to align themselves a little bit more with these students and their background,” Ruedes-Garcia said. “So if we align our values, our traditions and our practices a little bit more with the college students that are enrolled in our institutions, there might be an increase in that cultural capital.”

According to Ruedes-Garcia, minority-serving institutions like historically Black colleges have the potential to increase studentsʼ cultural capital.

“You have historically Black colleges and universities and you know by design they are meant to align more with that African and African American culture,” Ruedes-Garcia said. “And so when the student that identifies as Black enters an HBCU, they might come in with a little bit more cultural capital because that campus culture is more aligned with the way that they grew up.”

Because this study mainly tested PWIs, Ruedes-Garcia believes more research can be done in the future with the SSF scale in different types of colleges like HBCUs and Hispanic-serving institutions.

“So next steps (would be) letʼs test this scale at HBCUs at TCUs, at HSIs, letʼs look at liberal arts colleges, private schools,” Ruedes-Garcia said. “Letʼs test it to make sure that it works in all of these places because the more that we can test it and give that thumbs up that it works in these different kinds of college campuses, the the stronger we can say this measure will accurately measure sense of belonging, no matter what type of student youʼre studying.”