University professors have been adapting their courses and expectations as artificial intelligence gains popularity.

“I admit, I spend a lot of time thinking about how to create assignments that won’t tempt students to just use a large language model to complete it,” said Dani Nyikos, professor in LAS, in an email interview. “But in a way, this does help me: ChatGPT is very good at completing ‘busy work,’ and I try to avoid that anyway.”

To avoid encouraging students who use AI to complete their assignments, professors are reevaluating assignment prompts and grading procedures. These adaptations make it more difficult for students to complete an assignment solely using AI and still earn a good grade.

“I’ve had to adjust not only what I ask about or how I ask questions, but also what I look for,” said Kay Emmert, professor in LAS. “I embrace much more imperfection in low-stakes writing because it demonstrates the person’s thinking. I’m much more interested in seeing how a person is thinking about a question, and how they’re applying it to specific examples, things that they’ve experienced or things they’re thinking about than whether they’re getting the perfect answer.”

However, while these measures are being put in place to discourage students from the complete usage of AI, professors have also been incorporating AI education and experimentation into their coursework.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Marisa Peacock, professor in Media, will teach an AI in advertising course this spring. The goal of this course is to give students experience using AI in advertising, as well as educate them on its potential drawbacks.

“So we do a lot of in-class exercises to really give us experience,” Peacock said. “We’ll do the human output, and then we’ll do the AI output, and we’ll compare and contrast, and we’ll figure out, ‘What is it good at? What does it need more work at?’ It’s meant for every student to kind of come to their own conclusion, and hopefully, have a project or a portfolio at the end of it that shows the different ways that they have used AI to produce things.”

Similarly, Nyikos and Emmert create activities for their students that allow them to experiment with AI and come to their own conclusions about its strengths and weaknesses.

In her writing courses, Emmert has her students practice using AI during a singular step of the writing process for each assignment. Each assignment focuses on using AI for a different step of the writing process so that students can determine where its assistance is most helpful.

The professors noted that as students utilize AI, they can understand the software flaws firsthand.

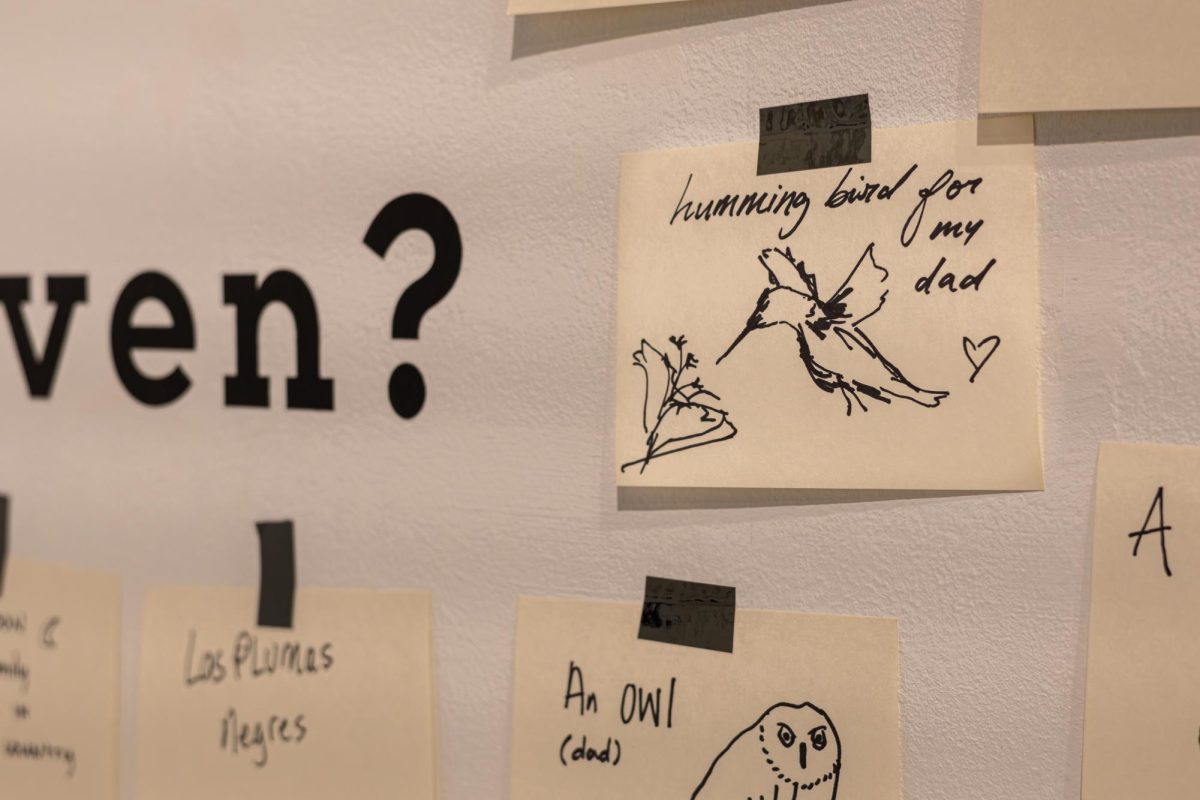

In addition to finding issues with the content AI produces, students are also becoming more educated on the ethical concerns surrounding AI. Two ethical concerns AI raises are environmental damage and potential theft of intellectual property.

According to the UN Environment Programme, the data centers where AI is housed require a substantial amount of raw materials, produce hazardous electronic waste, use large amounts of water and utilize fossil fuels for energy.

Additionally, artists have recently shared frustrations with having their work unknowingly train AI.

Emmert expressed that some of her students are aware of these concerns and have chosen not to use AI. In these cases, Emmert creates different tasks for those students so they can continue educating themselves on AI without having to use the software explicitly.

“That way, people who do want to take an ethical stand against contributing to this technology, they’re not forced to choose between a grade and their beliefs,” Emmert said.

At the end of the day, whether or not students use AI, the goal of education is to stimulate critical thinking. These professors believe that no matter how much students use AI for assignments, they must use critical thinking.

“I think it’s funny,” Peacock said. “Sometimes when you are using AI as your crutch, as your mechanism, to cheat the system, you’re actually working harder than if you just did the work. And so learning is still going to take place. I hate to break it to any student who’s hoping to bypass that, but sometimes the act of you trying to rework things so that detectors can’t find it is actually a really great way to learn the material.”

Nyikos urges her students to be wary when using AI, even if to ideate for an assignment.

“I encourage people to treat AI like a drunk uncle: It can be useful to bounce ideas off of, to help you brainstorm or to give you some kind of feedback, but whether those ideas will be any good or whether the feedback will be accurate or useful isn’t sure, so it’s important to treat everything it outputs critically,” Nyikos said.

Despite its ethical concerns and functional drawbacks, it is pertinent that students receive education about AI and are given space to experiment with it.

Many industries are adapting to technological developments; for students to be fully prepared for their future, they must know how to use AI properly.

“We’ve been hearing a lot from employers that AI isn’t going to replace you,” Peacock said. “People who know how to use AI are going to replace you.”