Meth, long the scourge of rural America, finally seeps into pop culture

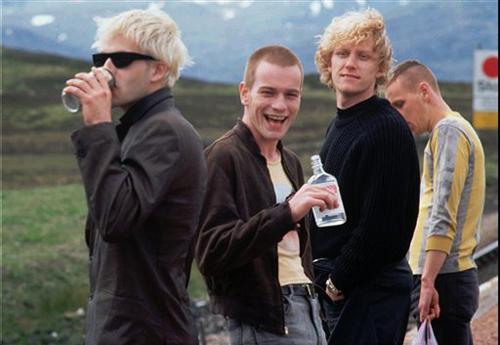

This undated photo released by Warner Bros. shows, from left, actors Johnny Lee Miller, Ewan McGregor, Kevin McKidd and Ewen Bremmer in a scene from the film “Trainspotting.” Drugs and pop culture have had a long and healthy relationship. But despite bein Daniel Liam, The Associated Press

Feb 15, 2008

NEW YORK – Vince Gilligan needed a character who would do something truly despicable. So he turned to the ugliest thing he could think of: methamphetamine.

The result is the new AMC series “Breaking Bad,” where Gilligan’s chemistry teacher protagonist, broke and dying of lung cancer, decides to leave his family financially secure by cooking and dealing meth.

Gilligan, creator and executive producer of the drama, said meth “seemed like somewhat untilled ground” in TV and movies. His show is evidence of how methamphetamine, the most destructive drug in the country for more than a decade, has only recently begun to seep into pop culture.

Such reticence is unusual for Hollywood, which has long been fascinated by drugs.

Think of cocaine and you’re likely to recall the 1980s TV series “Miami Vice” or the 1991 film “New Jack City.” Heroin has “Trainspotting” (1996) or “The Basketball Diaries” (1995). There are many more, going all the way back to Billy Wilder’s “The Lost Weekend,” the 1945 film that chronicled alcoholism.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Now, meth-related work is beginning to accumulate, with a trashy sensibility unique to the drug. The meth milieu is houses turned into disheveled laboratories and left reeking of toxic fumes. The common thread to portrayals of meth is depravity – it’s the lowest of lows, an unnatural, creepy fusion of toxic chemistry and backcountry dirt roads.

Before “Breaking Bad,” Val Kilmer played a meth addict in 2002’s “The Salton Sea.” One of the first noteworthy novels to tackle meth, Mark Lindquist’s “The King of Methlehem,” was published last summer. In January, the Drive-By Truckers released the song “You and Your Crystal Meth,” a lamentation of a friend’s addiction. The little-seen 2001 film “Cookers” turned a meth lab into a haunted house; an upcoming episode of the IFC sketch show “The Whitest Kids You Know” includes a parody song listing meth’s ingredients. And in last year’s “The Lookout,” Jeff Daniels’ character blames the drug for his blindness.

“This was a while ago,” he says, “before meth was fashionable.”

Methamphetamine was around for decades before a resurgence in the 1980s originated on the West Coast and swept across the country, taking firmest hold in poor rural areas.

More than 5 percent of Americans aged 12 or older have used meth at least once, according to the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Experts have argued that lawmakers have been slow to react. Slower still have been the filmmakers and writers of Los Angeles and New York.

“If (prevalent meth use) had been going on in Westchester County, New York, or Bethesda, Maryland, methamphetamine would have been a national priority 15 years ago,” said Rick Rawson, associate director of UCLA’s integrated substance abuse programs. “It just hasn’t hit the media centers where generally something like that gets attention.”

Patterson Hood, one of the singers and songwriters in the Drive-By Truckers, witnessed the effects of meth firsthand in his Alabama hometown, which “really got hit hard a few years back.” He penned “You and Your Crystal Meth” in response.

“At the time, nobody was talking about it,” said Hood. “There wasn’t songs about it; it wasn’t getting much attention from the press.”

Hood finishes the song with a haunting verse: “Indiana and Alabama, Oklahoma and Arizona/ Texas, Florida, Ohio, Small town America, right next door/ Blood soaked your pillow red; You and your crystal meth.”

Hood said the song has had a surprisingly polarizing effect on fans, resonating with those from middle America, while those from cities “don’t get it.”

Rock ‘n’ roll has been connected with drugs nearly since its inception. Simply the names of drugs suggest a tune: “Cocaine,” by Eric Clapton; “Heroin,” by the Velvet Underground.

One of the very few songs about meth was written by Bruce Springsteen more than a decade ago. “Sinaloa Cowboys” tells the story of a Mexican immigrant who dies in an explosion at a meth lab. Singer-songwriter James McMurtry, son of author Larry McMurtry, has also frequently sung about meth and “cooking speed.”

“It’s not a very romantic thing to sing about,” said Hood. “There’s nothing really cool or hip about it like some drugs have been at various times in our culture.”

It’s not hard to recall those times: psychedelia in the ’60s, cocaine flashiness in the ’80s, heroin chic in the ’90s.

“When you think back on shows like ‘Miami Vice’ and movies like ‘Scarface,’ cocaine sort of inadvertently became glamorized,” said Gilligan. “It became associated with fast times and high living.”

The utter lack of cool in meth addiction, Gilligan added, is “maybe a good reason why meth didn’t make it into TV and movies for as long as it did.” Crack was equally despicable, but its urban roots made for a quick transfer into pop culture.

When Michael Mann brought “Miami Vice” to the big screen in 2006, the drug business was portrayed as cold, calculated and extremely violent; the sexiness of the TV show was gone. The drugs had changed, too – one of the villains in the film resides in a meth-ridden trailer home.

While glamorization is always an issue when representing drug use, fictional works can be powerful tools in expanding the public’s understanding of a drug like meth.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” said Rawson. “The fact that (glamorization) hasn’t happened with methamphetamine may have contributed to less spread in some geographic regions of the country. But the other side of the coin is it’s been very difficult to get methamphetamine onto the national agenda.”

Increased legislation and a crackdown on domestic cookers may have turned the tide. A threat assessment published in December by the National Drug Intelligence Center concluded meth use has stabilized nationally since 2002. While traffickers from Mexico and Asia have kept meth on the market, domestic production has decreased “dramatically” since 2004.

Those who are fictionalizing meth use hope their work will help the declining trend continue.

“We don’t intend to glamorize it at all,” said Gilligan. “It’s more the ugly realities that we want to present.”