Cooties and crushes: Brain region finds new role in development

Apr 27, 2015

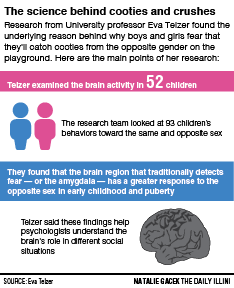

Glance at a playground — you’ll see boys and girls running around, trying to avoid catching “cooties” from each other. It’s normal behavior for young children, and according to research by University psychology professor Eva Telzer, it’s caused by the brain region that recognizes important environmental stimuli: the amygdala.

These behaviors show researchers like Telzer just how important the concept of gender is for children as they grow and learn about the world. They build their own gender identities, leading them to prefer those who are in the same group.

For many years, psychologists thought the amygdala’s only function was to activate when a fearful stimuli was present. Recent research from William Cunningham of Ohio State University and Tobias Brosch of New York University suggests that the amygdala’s sole function isn’t just to convey fear, but it also indicates when stimuli in the environment are important.

Telzer’s study, “‘The Cooties Effect:’ Amygdala Reactivity to Opposite- versus Same-sex Faces Declines from Childhood to Adolescence,” found that the amygdala’s response to gender increases from ages 4 to 7. Then, it increases again in teenagers.

Telzer examined the brain activity in 52 children, measuring the flow of oxygenated blood into the brain using an fMRI. The research team also looked at 93 children’s behaviors toward those of the same and opposite sex.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Telzer’s study reinforced Cunningham and Brosch’s research.

“So in early childhood, the opposite sex is interesting because of this idea of cooties; while in puberty, the opposite sex is interesting because it’s potentially this idea of crushes,” Telzer said. “It’s this kind of neural signal that we think is involved in detecting developmentally appropriate things that are salient or interesting.”

Graduate student in psychology Yuta Katsumi said the amygdala’s response depends on what is important to the subject.

“What’s really interesting about the amygdala is that it flexibly responds to stimuli that carry some motivational significance, but the definition of ‘significance’ seems to vary depending on who sees the stimuli,” Katsumi said over email, referring to a study done in 2013 by Natalie Ebner of the University of Florida.

Ebner’s work found that older adults had an amygdala response when viewing same-age faces, but young adults did not.

Katsumi said in that case, age could be more important for older adults, as they may be reminded of “age-related changes in daily routines more frequently.”

The findings of increased amygdala response in puberty were surprising to Telzer and her team, as they showed how the amygdala could be involved in different age group’s responses.

“We were anticipating, kind of, the cooties effect. When we found this effect emerging again around puberty, it surprised us that the very same brain region was signaling potentially to different phenomenon,” Telzer said. “It was also exciting to see that this brain region could be involved in different things to better understand the brain’s involvement in the different ways we think, so one brain region’s not responsible for one thing — it could be responsible for multiple things.”

The results of the study have potential to assist researchers in understanding further how development can influence social categories. For example, a 2012 study done by Telzer indicated that, due to activity in the amygdala, race is becoming an important category for adolescents.

Katsumi said he sees potential for Telzer’s research to play a role in his own, which focuses on the neural mechanisms behind group membership in adults.

“By comparing people of diverse age groups, or even studying the same individuals over years, we might be able to elucidate how people change their perspectives of the contemporary complex social world across the lifespan, and how brain regions such as the amygdala might participate in this process,” Katsumi said.