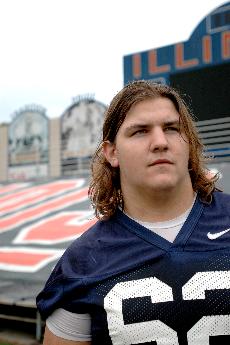

Lineman shares firsthand Katrina sorrow

Aug 29, 2006

Last updated on May 12, 2016 at 04:06 a.m.

Eight hundred miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River, Eric Block didn’t have time to worry about the hurricane that brewed in the Gulf of Mexico a year ago today. Then a freshman at Illinois, Block was learning to balance college classes, college football and the independence of college life. He was too busy settling into his dorm room, buying his textbooks and preparing for the season opener against Rutgers to pay much attention as the storm swelled.

“I didn’t hear about it until about two days beforehand,” says Block. “I was so wrapped up in football that I wasn’t paying attention.”

In the 52 weeks since walls of water rushed through his hometown of New Orleans, destroying much of it, Block’s family has been ripped apart and pieced back together. His home was ruined and rebuilt. He’s seen the city he loves brought to its knees – then struggle to rise again.

The only constant has been football.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“Football kept my mind off things,” Block says. “If I had sat around thinking about it, I might have wound up back home, and that really isn’t the place I should be right now.”

Eric Block was lucky; he was far away when the massive hurricane hit his city on Aug. 29, 2005. But friends say taking the lineman out of New Orleans didn’t take New Orleans out of the lineman.

“He’s just so in tune with the culture, the sense of community down there,” says Brit Miller, Block’s roommate and a sophomore linebacker. “He reads French, he cooks jambalaya. And he’s doing a heck of a job balancing everything.”

New Orleans today, Block says, is a tattered skeleton of the city where he grew up. There are hints of life returning, as homeowners rebuild and businesses reopen. But the past year has brought much stress to the Big Easy.

Just one year ago, New Orleans thrived with culture and character. A melding of southern and French influences gave the city its personality. Block says it was a place rich with distinct styles of music, cuisine and hospitality.

“It’s almost like you can feel the city breathing,” he says. “There’s such a pulse throughout the whole city; it’s something you can’t experience anywhere else.”

Before Katrina, the tourism industry was New Orleans’ largest employer. Millions of tourists and convention attendees each year created an industry that accounted for 35 percent of the city’s operating budget and generated $5 billion in visitor spending.

Some of Block’s favorite memories are of Saints games with his family. Before each home game Block’s grandmother would pack a purse full of aluminum-wrapped hot dogs to sneak into the stadium.

“I remember being at Saints games when I was four; I was born and raised a Saints fan,” Block says. “It definitely had an influence on me playing football.”

When Katrina hit, the Superdome, where Block attended so many Saints’ games, quickly became a refuge for thousands of New Orleans residents.

As the Category 5 hurricane approached Louisiana, the Block family considered waiting it out. They had been through this before, and floodwaters had never damaged their home in Metairie, a neighborhood a few miles from the heart of the city. Eric’s grandparents had never evacuated, and saw no reason to run from this storm.

It was Eric’s mother, Donna Block, who convinced the family to move inland. A nurse administrator at East Jefferson General Hospital, Donna Block learned that emergency workers were preparing for the worst – so she insisted that her family leave.

But, Block says, no one could have predicted the way water would pour from broken levees and flood the Gulf Coast. No one expected it to turn highways into canals, for the water to spread farther than previous hurricanes had ever reached.

“I was nervous, but I didn’t expect what happened,” Eric Block says. “I didn’t expect the city to flood. My neighborhood has never flooded. My house has been there for 40 years, and in 40 years it hadn’t flooded, so I figured we’d be alright.”

But when the storm passed and Donna Block returned to the family home – with an armed guard for security – she found 12 inches of water damage and four feet of mold crawling up the walls. All the furniture and most of the family’s possessions had been destroyed. It didn’t matter that looters had not reached the Blocks’ home. Floods had ruined almost everything of value.

“She said the couches and chairs, all the upholstered furniture looked like Chia Pets,” Roy Block says. “There was mold on everything.”

As she walked through the house, Donna Block called her son in Champaign.

“That’s when it really hit her,” Eric Block says. “As soon as she walked into the house, that’s when it became real.”

With nowhere else to go, Roy and Joel Block drove to Champaign for Eric’s first game. Roy Block says football provided an appreciated distraction not only for his son, but for the entire family as they worked to piece their lives back together.

“It gave us two or three days every couple of weeks when we could just get away,” Roy Block says. “It was something to look forward to.”

The Blocks, like the rest of their city, have spent the past year cleaning up the mess Katrina left in its wake. They were back living in New Orleans by October and moved into their house in late May, but are still finishing the last of the reconstruction. When Eric Block gets to go home, he is often put to work as his family rebuilds.

Last Christmas, Block worked for a lumber company, delivering building supplies around the city. He said he saw people working together to rebuild, but was hit hard when passing by the ruins of friends’ homes.

“Because my high school drew from everywhere, I had friends throughout the entire city,” Block says. “Driving past old hangouts was tough because you realized people’s houses were destroyed, and you didn’t even know if they’d come back.”

Slowly, New Orleans is returning. As of July 1, 1.17 million people lived in the city – just 300,000 fewer than before the storm. Another 100,000 are expected before the year’s end.

Block is once again focused on preparing for Illinois’ season opener as a potential starting center.

Three states away, New Orleans is also looking to the future.

“New Orleans culture will never die, it will never go away,” Block says. “Even if New Orleans was destroyed, it would spread other places. If you move there, you’re just part of it … It’s like no other place.”