English professor compiles American Indian poetry

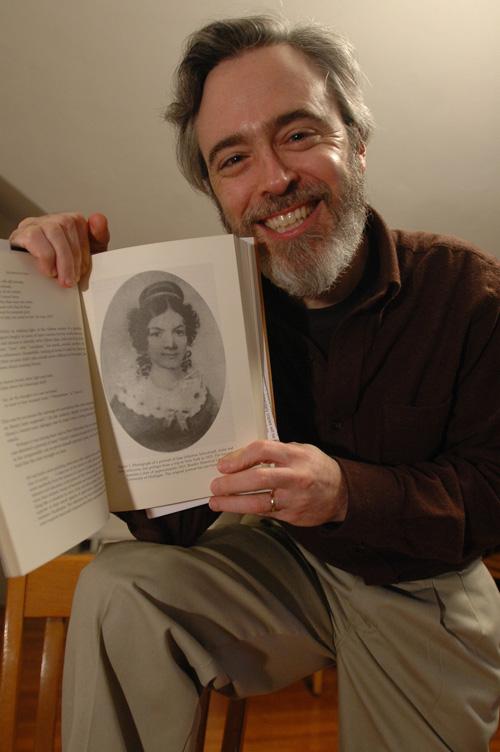

Robert D. Parker, professor of English and American Indian studies, poses with his new book, “The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky: The Writings of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft,” on Tuesday, Jan. 23, 2007. Joseph Lamberson

Jan 24, 2007

Last updated on May 12, 2016 at 07:14 a.m.

Many students and scholars have read about the “gloomy pine trees” in Henry Wordsworth Longfellow’s famous poem “The Song of Hiawatha,” but few know the poem’s actual roots.

Robert Dale Parker, English professor at the University, traces the poem’s history back to the work of a woman named Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, the first American Indian literary writer. Parker assembled the entirety of Schoolcraft’s poetry and prose for his new book, “The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky: The Writings of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft.”

“(Schoolcraft’s work) defies our stereotypes of writing at the time,” Parker said. “It gives us an everyday picture of the life she was living.”

Born in 1800, Schoolcraft began writing as a teenager, inspired in part by the War of 1812. Her native Ojibwe tribe, situated in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., fought against the U.S. in the war and underwent rapid modifications after the U.S. victory.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“(The Ojibwe tribe) had to go along with being American and not British,” Parker said. “In her writings, (Schoolcraft) meditates over the abruptness of the change from life in the woods to life with laws.”

Other frequent topics in Schoolcraft’s literature include nature, her hometown of Sault Ste. Marie, and everyday life. Her father John, an Irish fur trader and book lover, provided her with an early English education to accompany Ojibwe teachings.

“(Schoolcraft) was completely conversant in the English language,” Parker said. “She grew up speaking Ojibwe and English.”

Parker explained that Schoolcraft’s impressive body of work, comprised of over 70 prose and poetry pieces in both the Ojibwe and English languages, has been ignored since her death in 1842 largely because of her husband, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. A federal Indian agent and well-published ethnographer, Henry depended on his wife’s work and would often “bury it in his writings,” Parker said.

The publication of Parker’s book coincides with a record number of courses offered by the American Indian Studies Program, of which Parker is an affiliated faculty member. The program now offers 11 courses, up from just two in the 2004 fall semester.

Unlike any other University ethnicity-based academic program, the American Indian Studies Program is run through its cultural house, in this case the Native American House, 1204 W. Nevada St.

“We want to replicate the learning and educational process that takes place in many tribal communities,” said John McKinn, assistant director of academic programming at the Native American House. “We don’t differentiate an academic program from a cultural program.”

Parker stated a similar mission in discussing his book, noting that it “speaks to a mainstream audience as well as an Indian one.” Schoolcraft, meanwhile, may not have had an audience in mind when practicing her craft.

“She wasn’t writing for publication,” Parker said. “She was writing because she loved to write.”