Study reports UI has good work environment for pre-tenure faculty

Sam Copeland

Feb 12, 2007

Last updated on May 12, 2016 at 07:52 a.m.

While private schools are traditionally thought of as better places to work, recent statistics show that the University more than holds its own.

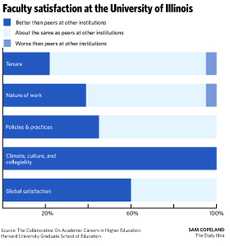

In a study released by the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education, a research group based at Harvard University, the University is one of five institutions to achieve exemplar status in four of seven categories that reflect junior faculty satisfaction.

The study, administered between October 2005 and January 2006, compiled data from surveys of more than 4,500 junior faculty members at 51 institutions nationwide.

“This is a report (sent to institutions) where they find out what’s working and what’s not,” said Kiernan Mathews, assistant director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Junior faculty, or pre-tenure professors who are on a tenure track, ranked the University highly in four areas: work and family balance, nature of work, policy effectiveness, and global satisfaction.

“We overall as an institution do well,” said Linda Katehi, provost and vice chancellor for academic affairs. “At the same time, (this study) places the responsibility to do better.”

Katehi explained that the University could improve by reaching each professor on an individual level instead of “providing molds for (them) to fit in.”

“Success is not just meeting standards,” she said. “What makes individual faculty successful is their ability to develop a career that meets their own personal needs.”

Carol Livingstone, associate provost for academic affairs, said that the University needs to improve even in categories where it was rated as exemplary, such as work and family balance.

According to the study, the University has a highly rated spousal/partner hiring program, which works to provide jobs in the Urbana-Champaign area to the partners of faculty. Still, 12 percent of junior faculty members are living in entirely different communities than their spouse or partner.

“We’re not perfect,” Livingstone said. “These surveys are helpful in determining where we can improve.”

Traditionally, new faculty members are welcomed with orientation programs at the university level and mentoring programs within different schools and departments. Depending on their field, incoming professors can receive start-up packages for research or even labs costing around $1 million, Livingstone said.

“(Professors are) a big investment of time and resources,” she said. “(And) recruiting and retaining the best faculty members is one of the most important jobs of the department heads, the deans and the administration.”

Nan Goggin, associate director of the school of art and design, serves as co-chair of the Teaching Advancement Board, which encourages excellence and innovation in teaching. Financially, the board awards grants to departments and schools in order to assist professors who want to travel to workshops or seminars.

“The (Teaching Advancement Board) is the only place on campus that has funding and support for teaching,” Goggin said.

Mathews explained that the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education study reflects a movement away from monetary concerns among junior faculty members.

“This new generation of faculty have different priorities,” he said. “Things like work and family and collegiality are important to them, and not necessarily compensation.”