Investigative report: Scholarships fall short

Mar 7, 2007

Last updated on May 12, 2016 at 08:38 a.m.

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a two-part series.

Former director of the University’s Executive MBA program Robert van der Hooning says the administration of the College of Business illegally and unethically rescinded admission to tens of veterans who applied to the program. When he tried to seek help and correct those actions, he was forced to “take the fall,” he said.

He was subsequently fired and has filed a lawsuit against the University under the Illinois Whistleblowers Act.

One of the major concerns of the administration, van der Hooning said, was absorbing high costs from the shortfalls in the Illinois Veteran Grant (IVG). Originally the college started a scholarship partnered with the IVG that would pay 30 percent of any shortfall in a veteran’s credits.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The Illinois Veterans Grant was started in 1967 by the Illinois Student Assistance Committee to provide tuition waivers to veterans attending state universities. Beginning in fall 2005 the IVG was expected to include all mandatory fees, as well as tuition.

To be eligible, someone must have been a resident of Illinois six months prior to their military service, have served on active duty for at least one year, be honorably discharged and move back to Illinois within six months of that discharge.

What puts universities in a hard spot is they are required by law to waive all tuition and mandatory fees for qualified veterans, whether or not the funding is actually available from the IVG.

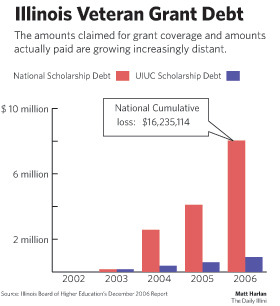

According to the Illinois Board of Higher Education’s December 2006 report, the University alone has been forced to absorb over $2 million since fiscal year 2002. This is also with the number of recipients decreasing from 105 in 2002 to 81 in 2006.

Much of this shortfall is due to the nature of the program itself. The grants are given based on credit units, not dollar amounts. Each veteran is given 120 credits, equal to hours, to use at any school or university. The grants do not equate to a dollar amount like the Montgomery GI Bill, for example.

Whether veterans use those credits at a community college or university is up to them. Therefore, if more veterans decide to use their credits at universities instead of community colleges, it will cost the IVG more money to fund their education.

Administrators for the College of Business worked to get the definition of “tuition” changed for the program to include many Champaign-Urbana campus fees rolled into “tuition.” Many of these fees were not applicable to students in Chicago, such as housing and McKinley Health Center fees.

But, the administration did this originally in hopes the IVG would cover a higher percentage of the total cost for veterans. This was before they decided to cut down the number applying to the program.

“Well, if two-thirds of your University definition of tuition is tuition, and one-third is (non-mandatory) fees, IVG is only going to cover two-thirds,” van der Hooning said. “This means that the military guys have to come up with one-third of ($72,000),” van der Hooning said. “For a lot of these guys, and remember almost 60 percent of them are married and have kids, they can’t do that.”

Rescinding Admissions

After administrators realized the possible funding shortcomings of so many IVG-eligible veterans in the program, they began to “reverse-engineer” deadlines and other technicalities to disqualify many of them from admission.

These faculty included Avijit Ghosh, dean of the College of Business; Larry DeBrock, associate dean for professional programs in the college; Sandra Frank, associate dean for admissions in the college; and David Ikenberry, interim director for the EMBA program.

“(Ghosh) wanted me to do a class of 45 to 50. And his justification was ‘a good class of 45 or 50 should be the target. Additional cash flow from the additional (civilian) students, that needs be the focus,'” van der Hooning said, reading an e-mail he received from Ghosh.

In another e-mail between Ghosh, DeBrock, and Frank on May 19, 2006, van der Hooning was told to look for criteria to cut the number of veterans by over 60, down to between 15 and 17.

However, in later May and June, van der Hooning was told to continue recruiting civilians for the program, he said.

When van der Hooning decided to seek legal council, he was directed to make copies of all e-mails and documents related to this admissions process.

Documents obtained by The Daily Illini include a picture of a dry erase board van der Hooning said was taken after a May meeting between top administrators, including current Interim Director Dave Ikenberry. Scribbled on the board are calculations used to figure how more civilians in the program could bring more money, as opposed to students supported by the IVG.

“Dave Ikenberry came up to Chicago and was helping me work on how to rescind people,” van der Hooning said.

Ikenberry said he is only the interim director, and before July 1, 2006, he was not aware of any of the issues that were going on.

“I was aware primarily as a (general faculty member) – on a month-by-month basis – of what’s going on,” Ikenberry said. When asked why he is mentioned in van der Hooning’s lawsuit, Ikenberry said “I have no idea.”

“Keep recruiting civilians!” is circled in the middle of the dry erase board. Along the right side are details of how many “Quick-Admit” applicants to rescind per day to meet an ideal mix of veteran/civilian by the time classes started.

“At the time we only had 19 civilians in the program that was now capped at 60. But I had maybe 65 military guys that had been conditionally accepted,” van der Hooning said. “But I had a gap … of 16 more civilians to meet their quota.”

Unconventional Admissions

Once van der Hooning successfully pitched the idea of the IVG partnership to the college administrators in early 2005, he realized the difficulties these veterans could face in applying.

It would be time consuming to gather school records for a person stationed all over the country over a period of years, ask for letters of recommendation, and then secure post-deployment living plans. This is when van der Hooning received a suggestion to use a “Quick-Admit” program developed by current Interim Dean of the EMBA program, David Ikenberry.

This program examines the basic academic profile of an applicant, as well as other relevant information such as work experience, as a means to obviously tell whether or not that applicant would be accepted into the program.

It was used by Ikenberry at the time to recruit foreign students into the Masters of Science in Finance program, van der Hooning said.

“The rescinding … was based on a procedure called ‘Quick-Admit,'” van der Hooning said. “I’d like to take credit for, but I can’t because I got it from Ikenberry.”

However, once Ghosh wanted to decrease the number in the program, van der Hooning was instructed to create new requirements that would disqualify many of these applicants.

The solution: rescind offers to any applicant, specifically veterans, whom had not completed the formal application within 10 days of being Quick-Admitted. Van der Hooning said the normal time for completion of this formal application is 30 days.

In the original Quick-Admit letters, no deadline was provided on when to complete the formal application. And many of these rescind letters went to men still out of the country in Iraq and Afghanistan, van der Hooning said.

“Ghosh actually defended this to the Lt. Governor (Pat Quinn),” he said. “(Ghosh) actually said we did this as a convenience, as a courtesy… to men and women who are serving our country.”

But, the University does not honor any such Quick-Admit process over the normal application process, said Robin Kaler, University spokeswoman.

Anyone applying to the College of Business or EMBA program applies to, and is accepted by, the Graduate College. The College of Business does not have a final say in who gets admitted. They can simply recruit applicants and make recommendations to the admission board.

Once many of these rescind letters went out, letters from these denied veterans began flowing into Congressman Rahm Emanuel’s office and Lt. Gov. Pat Quinn’s office. Both supported the creation of a partnership with the IVG, and had personally recommended some applicants.

Emanuel and Quinn wrote letters inquiring into these men being rescinded admission. Then on June 14, Ghosh personally sent letters to the rescinded veterans assuring them the college would honor all commitments it made.

But, only after van der Hooning was terminated the month before.

“If it wasn’t for Quinn, if it wasn’t for Emanuel, this would have been cut back to 15 to 17 because that was my initial order,” van der Hooning said.

The EMBA program has since doubled in size since last year, from 32 to 65 students. Due to attrition, the current class is 58. Also, last year only 8.6 percent of students received IVG benefits. This year, 60 percent of the class receives these benefits, or 39 students.

“We honored every commitment, military or civilian, regardless of whether they were authorized,” said Kaler.

Sandra Frank, associate dean for admissions, refused comment for this story. Avijit Ghosh and Larry DeBrock referred all questions to Robin Kaler.

Currently, no information is available on the College of Business’ Web site or informational brochure on any scholarships partnered with the IVG, only that the IVG is a form of financial aid to prospective students.

“What we’re really encouraging people to do is if they are eligible (for the IVG) to get in contact with us,” Ikenberry said.

Amanda Graf, Kathleen Food and Jonathan Wroble contributed to this report.