Gene therapy may have killed woman

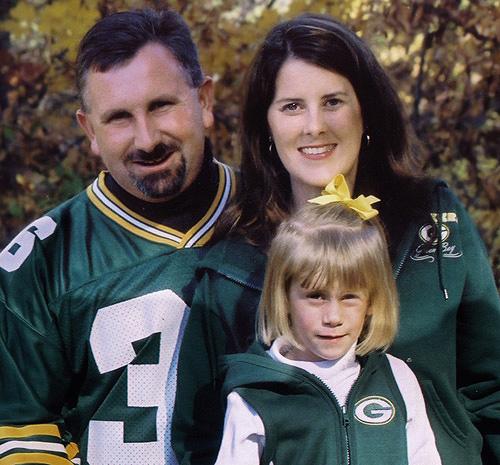

The Mohr family poses in this undated photo supplied by the family on Sept. 10. Jolee Mohr died in a Chicago hospital in summer 2007, three weeks after taking an experimental treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. The Associated Press

Sep 17, 2007

Last updated on May 12, 2016 at 03:51 p.m.

TAYLORVILLE, Ill. – A few hours before she died this summer at the age of 36, Jolee Mohr lay in a Chicago hospital so swollen by internal bleeding and her failing kidneys that her husband decided against bringing their 5-year-old daughter to say goodbye. The girl wouldn’t have recognized her mother.

Robb Mohr couldn’t bring himself to watch her die and he spent his wife’s last hours talking with her helpless and puzzled doctors. One vowed to get to the bottom of the illness, and there were several clues to go on.

The most unusual was this: Jolee Mohr fell ill the day after her right knee was injected with trillions of genetically engineered viruses in a voluntary experiment to find out if gene therapy might be a safe way to ease the pain of rheumatoid arthritis. She was dead three weeks later.

The sponsor of this nationwide experiment, Targeted Genetics Corp. of Seattle, has halted the work and more than 125 patients are being evaluated, according to a company spokeswoman. No other problems have been reported, and the company believes patients were adequately informed of the treatment’s risks.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

U.S. health officials are investigating Mohr’s death, and the case is expected to be discussed Monday by advisers to the National Institutes of Health. There’s a lot at stake, including answers for Robb Mohr, and the interests of Targeted Genetics. But there also are questions about how medical studies are done and how much study volunteers are told of the risks.

“To me, it’s an avoidable death,” Mohr said during an interview at his home amid the cornfields of central Illinois. “And you’re going to have to really show me a lot of stuff to convince me that it wasn’t.”

There have been more than 800 gene therapy studies involving 5,000 U.S. patients since the NIH approved the nation’s first human gene transfer study in 1989. Yet there are no approved therapies despite 17 years of research, and the only major success – a cure for the rare inherited immune disorder known as “bubble boy disease” – came with a high cost: leukemia linked in 2003 to the virus that delivered the treatment.

Still, the 1999 death of Arizona teenager Jesse Gelsinger is the only reported fatality definitively linked with a U.S. gene therapy study, an NIH spokesman said. And Dr. Theodore Friedmann, who once headed the NIH committee that oversees gene therapy experiments, said developments in medicine often come with problems, even death.

Even if gene therapy is found to be the cause of Jolee Mohr’s death, Friedmann said, the method remains promising.

“There’s no question that this event is tragic for the family and the woman involved,” he said. “It does simply point to the fact that we have a lot more to learn.”

When Dr. Robert Trapp of the Arthritis Center in Springfield told Jolee Mohr about the gene therapy study, she had lived with rheumatoid arthritis for 14 years, her husband said. She kept the pain, stiffness and swelling in her joints under control with medication.

Mohr seldom missed work at her full-time data entry job for the Illinois secretary of state. She went to church and volunteered at the county fair. She loved to read and work in her garden. She and Robb had just bought a boat and were planning to build a new house. Their only child, Toree, was getting ready for kindergarten.

To enroll in the study, every patient had to have some form of inflammatory arthritis. Jolee Mohr had faith in Trapp, her doctor for seven years, her husband said.

“You trust your physician. He’s your doctor. You trust him like you do your minister,” Robb Mohr said.

Jolee Mohr thought the experimental treatment might relieve the chronic pain in her right knee, her husband said, though this stage of the study was simply to find out if the treatment was safe. Bioethicists talk of a “therapeutic misconception” – a belief among patients in early stage research that they will get better.

Robb Mohr said his wife believed.

Jolee Mohr signed a 15-page consent form Feb. 12. “Knowing her, she probably didn’t read through it,” her husband said.

The form mentioned some scary possibilities. It said that the genetically altered viruses in the study – called tgAAC94 – “could spread to other parts of your body. The risks of this are not known at this time.”

AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner reported from Chicago