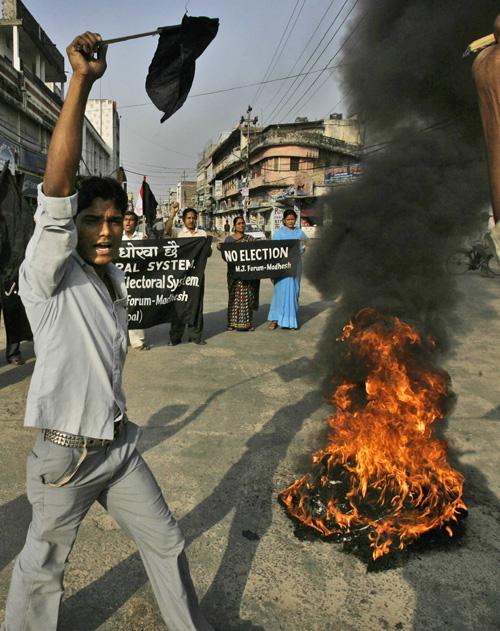

Violence in Nepal surges before election

Activists of Madheshi Janadhikar Forum, a breakaway party from Madheshi Forum, demonstrate against assembly elections, in Janakpur, 385 kilometers (240 miles) east of Katmandu, Nepal, on Wednesday. Nepal votes April 10, for an assembly that will rewrite i Manish Swarup, The Associated Press

Apr 10, 2008

Last updated on May 13, 2016 at 09:34 a.m.

KATMANDU, Nepal – An outburst of bloodshed that killed eight people cast a shadow on an election Thursday meant to cement Nepal’s peace deal with communist insurgents, stoking fears of more violence on voting day.

The voting for a new assembly is intended to usher in sweeping changes for this long-troubled Himalayan country, and will likely mean the end of a centuries-old royal dynasty.

But with one candidate gunned down, a protester shot dead by police and six former rebels slain in a clash with police, it was clear that fashioning a lasting peace in this largely impoverished, often ill-governed and frequently violent country won’t be easy.

“For the peace process to be successful, the election needs to be credible,” said Yubaraj Ghimire, editor of the newsweekly Samay. This week’s violence “raises a lot of questions about how credible the election will be.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The demonstrator was killed Wednesday after police fired on a mob smashing shops and vandalizing buses to protest the slaying a day earlier of a candidate in the mountainous Surkhet district, the area’s police chief, Ram Kumar Khanal, said. Police did not have any suspects in the candidate’s slaying, he said.

A curfew was imposed in the remote district, and authorities said they would delay voting in the area by at least a week while the election would go ahead elsewhere.

Dozens of parties, from centrist democrats to former Maoist rebels to old-school royalists, were competing for seats in a new Constituent Assembly, which will govern Nepal and rewrite its constitution.

The vote is the first in the two years since King Gyanendra was forced to end his royal dictatorship and the Maoist movement gave up its decade-long fight for a communist state that left about 13,000 people dead.

For the 27 million people of Nepal, wedged between Asian giants India and China, the vote brings a promise of peace and an economic revival in this grindingly poor land that often more resembles a medieval fiefdom than a modern state.

But after weeks of near-daily clashes between supporters of rival parties and a handful of small bombings – including two in Katmandu on Wednesday that caused no injuries – the mood on election eve was one of ambivalent optimism.

“We have no choice but to be hopeful,” said Biraj Shresthra, a 43-year-old who runs an electronics shop in Katmandu. “We’ve seen so much fighting. Maybe now it will stop.”

Campaigning ended Monday and security was tight across the country Wednesday as Nepalis scrambled back to their home towns and villages. Many businesses closed and streets were empty in Nepal’s ordinarily traffic-choked cities.

Chief Election Commissioner Bhoj Raj Pokhrel told reporters that “we are all concerned regarding election day violence.”

The biggest threats to a peaceful vote were armed ethnic minorities on the southern plains, where fighting has twice delayed the poll, and the Maoists, whose supporters are accused of roughing up rival candidates and attempting to intimidate voters.

Supporters of other parties – from the centrist Nepali Congress to the left-wing Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) – also have engaged in fights.

But the majority of the violence since the start of the election campaign has been by the Maoists, according to a United Nations mission overseeing the vote.

On Tuesday, a gang of Maoists clashed with police in southwestern Nepal after the former insurgents attacked a prominent candidate from a rival party. Initial reports said one person was killed, but police said Wednesday that six of the former rebels died.

The Maoists are the wild card. They have 20,000 former guerrillas camped across the country and their weapons are easily accessible in containers where the arms are stored under a U.N.-monitored peace deal.

It would be easy for them to resume their insurgency if they don’t like the election results, and one of the big questions was whether they would do well enough to keep them engaged in the peace process.

Most observers believe the Maoists would place second or third behind Nepal’s traditional political powers, the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist).

The Maoists insisted they would respect the voters’ decision, and their leader urged restraint following Tuesday’s clash.

“We should respond to such provocative crimes by the feudal forces … through demonstrations of patience and determination in favor of free and fair polls,” said Pushpa Kamal Dahal, whose goes by his rebel nom de guerre, Prachanda, which means “the fierce one” in Nepali.

Associated Press writer Binaj Gurubacharya contributed to this report