Increased tax brews trouble for Pittsburgh drinkers

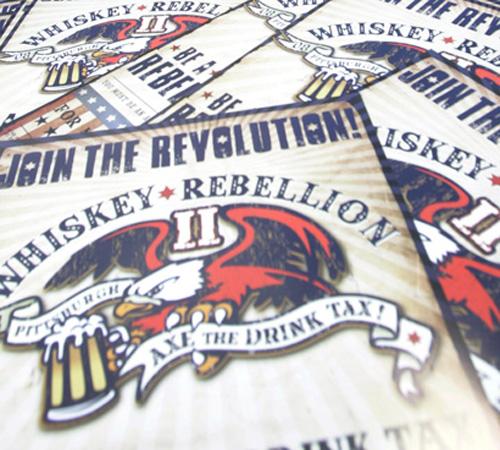

A stack of posters promote a referendum on the Allegheny County 10 percent tax on poured alcoholic drinks in Pittsburgh on Friday. Keith Srakocic, The Associated Press

Jun 16, 2008

Last updated on May 13, 2016 at 11:39 a.m.

PITTSBURGH – A stiff drink comes with a stiff tax in Pittsburgh and surrounding towns these days, and that has made the county executive public enemy No. 1 in some quarters, reviled by name in song and on bar bills.

Even comedians have gotten into the act, complaining that rising drink tabs meant fewer people coming to see them perform and pouring wine and liquor into a river in a mock restaging of the Boston Tea Party.

The 10 percent drink tax, in effect since January, was pushed along by Allegheny County Executive Dan Onorato to subsidize public transit. The two-term Democrat says he had no choice; swallow that, he said, or property taxes would have to be hiked.

Many bar and restaurant owners are frothing over the county surcharge, and are making sure that the name of its sponsor is as well-known as, say, Sam Adams and Jim Beam. With rising fuel and food costs and a weak economy, they say, the tax is just one big fly in their beer.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“I’ve been in this business for 40 years and I’ve never seen a more difficult or challenging time,” says Kevin Joyce, owner of The Carlton restaurant in downtown Pittsburgh.

Michael McDermott, who was nursing a lager at a downtown pizzeria, says he goes out only two nights a week now instead of three – just the kind of response bar owners fear.

“I cannot afford to drink as much as I used to,” says McDermott, 49, of Scott Township.

Signs have appeared in bars telling Onorato, only half in jest, that he is not welcome. Some bar receipts contain the notation “Onorato tax.” Online, one Irish balladeer croons: “Remember the tax you pay on every single beer and then tell old Danny boy that he’s not welcome here.”

One restaurateur even challenged Onorato to a charity boxing match, with the tax’s future at stake if he lost. Onorato chose instead to tend bar and give his tips to a Police Athletic League.

Now the brew-haha over the tax, which also applies to six-packs sold at bars, is taking a more serious turn.

A petition drive is about to get under way to try to repeal the 10 percent levy. Friends Against Counterproductive Taxation plans to begin collecting signatures Tuesday to put the issue to a referendum in November.

“He was hoping everyone would have forgotten about the tax,” says Tom Baron, president of big Burrito Restaurant Group, which runs 11 eateries in the county. “Instead, he’s facing Whiskey Rebellion II.”

The original Whiskey Rebellion was in 1794, a tax revolt in which western Pennsylvania residents played a major role. President George Washington fought back by calling up the militia.

Allegheny County will respond to the new Whiskey Rebellion with its own referendum, asking voters to pick between a property tax increase or the drink tax to maintain a transit subsidy required by law.

“I am not budging. They are not going to force a property tax on this county,” says Onorato, who has a background as a lawyer and certified public accountant. “I have to do what I have to do and they have to do what they have to do. I will put my faith in voters.”

As of March 31, the new drink tax had generated close to $9 million in the county, which has some 2,000 active liquor license-holders.

Opponents say the county is likely to get considerably more than the $32 million it needs to subsidize mass transit. The county executive says any surplus can be used for transportation capital projects.

Philadelphia, on the other side of the state, has had a 10 percent drink tax for 14 years. It helps pay for public schools.

They appear to be among the highest local drink taxes in the country, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, a trade association which opposes the Allegheny County tax.

At Pittsburgh’s Church Brew Works, owner Sean Casey isn’t posting anti-Onorato signs or otherwise bashing the county executive, but he understands why other bar and restaurant owners might be so angry, especially those in communities where customers can easily hop over to another county for cheaper drinks.

“When you are seeking to decimate somebody’s business, a lot of people are going to push back because they’ve got to protect their families,” he says. “Their livelihoods are threatened and they feel cornered.”