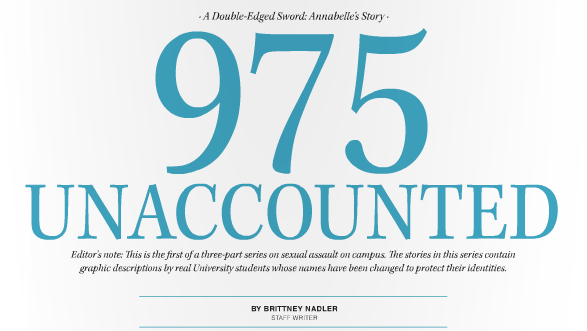

Federally mandated acts enforce greater University action in sexual assaults

Apr 24, 2014

Last updated on May 11, 2016 at 04:57 a.m.

Despite being warned by her brother, Jennifer met up with a guy two years older than her. He had a reputation as a jock whose friend circle included “the douchebags.”

“My brother didn’t like him, but he’s really cute, so of course I hung out with him,” she said.

They started to mess around in his car, and he wanted to go further — further than Jennifer wanted.

“He held me down, and I couldn’t really move, and I was in shock,” she said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

He took her virginity.

She put her feet on his chest, shoved him to the other side of the car and yelled at him to drive her home. When she got there, she got out of his car, crying hysterically, as she sat on her front stoop.

“I didn’t want to go inside and face my family, and I was bleeding a lot, and I didn’t know what to do or what to tell my mom because she did my laundry,” she said. “It was probably the worst night of my life.”

Jennifer stayed in for the next few weeks but got bombarded with harassing texts from him, one of which read, “You got blood on my shorts, you have to pay for it.”

She lied to her mom about what happened, saying he went further than she wanted and caused her to bleed, but she never said she was raped.

Jennifer’s assault took place the summer before she came to college, so knowing she would soon be far away from him helped, as did meeting better guys.

She never reported her assault and does not regret her decision. She said there are many privacy issues that come with reporting an attack, and she doesn’t think women feel comfortable coming forward, especially when police may turn to victim-blaming.

“Part of my reason for not reporting was I didn’t want people to think I was lying,” Jennifer said. “It is something you think will never happen to you or anyone you know, especially when the perpetrator is someone all of your friends know, so hiding it seemed like the best option.”

When the police are notified that someone has been sexually assaulted, there are three options: the assault can be reported, investigated and followed through for prosecution; the assault can be solely documented for possible future use; or if the assault was reported by someone other than the victim, the victim can choose not to talk to police at all.

The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, or Clery Act, is a federal mandate requiring all colleges and universities that participate in the federal student financial aid program to disclose crime information on campus and in surrounding communities. The Clery Act requires that all known assaults be included in the Annual Security Report crime statistics whether or not the victim wants to move forward with the investigation, said Lt. Tony Brown of the support services bureau of the University police department.

If a survivor does not want to make a police report, University police complete a Campus Security Authority report, and the assault is included in the statistics found in the Annual Security Report. On campus, there are close to 1,000 identified Campus Security Authorities, or CSA, who can contribute to the Clery Act even if there is no investigation, Brown said. A CSA is a campus police officer, security official or other official with student responsibility. CSAs are provided with information to determine if and when a crime should be reported to the security report and are required to complete formal training.

According to the, the reason behind incorporating CSAs is that students may be more inclined to report crime to non-law enforcement personnel.

Although Title IX is often associated with equality in sports, the law is very broad, saying schools cannot discriminate based on gender. Title IX is a “comprehensive federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally funded education program or activity,” according to the Department of Justice.

Under Title IX requirements, the University is required to follow up and do an independent investigation of all sexual violence that occurs on campus, Brown said.

“We try to empower the victim as much as possible in the circumstances and follow their wishes on how we investigate sexual assault,” Brown said. “Then we always give them the resources that are available both on campus and in the community.”

Though many resources are available, Jennifer said the issue of privacy can make them ineffective.

“Rape kits are very invasive, and I know they have to be to get the correct DNA, but it has to be done in a caring way that will make women and men feel more comfortable and less embarrassed,” she said.

***

On April 4, 2011, the Office for Civil Rights through the U.S. Department of Education issued a “Dear Colleague Letter” to address the issue of sexual violence on college campuses. A Dear Colleague Letter is a guidance letter used to help institutions interpret the law, said Kaamilyah Abdullah-Span, assistant director for the Office of Access, Diversity and Equity at the University.

The letter states that colleges and universities are not doing enough to address the issue of sexual misconduct. Abdullah-Span said assaults occur too frequently, and cases are not handled in the spirit of Title IX.

The letter states that schools are required to take immediate action to eliminate the harassment, address its effects and “conduct an investigation that is thorough and that is impartial and that is immediate,” Abdullah-Span said.

She added that the letter was issued to “make sure that colleges and universities are taking reports of sexual misconduct seriously and not minimizing sexual misconduct.”

By doing so, survivors are not further victimized by the institution’s inaction after the incident is reported.

“It’s critical for the community to know that if I report this, I’m not going to be shunned, that the University is going to take this seriously,” Abdullah-Span said. “Sexual assault happens. It happens on colleges and universities more frequently than we’d like to believe.”

If the complainant wants to file charges, the organization that handles the complaint has primary jurisdiction.

If the case is between two students and the victim wants to pursue disciplinary actions, the Office for Student Conflict Resolution has jurisdiction. If the assault is between a student and employee — such as an instructor, professor or teacher’s assistant — then the Office of Access, Diversity and Equity has jurisdiction, Abdullah-Span said.

Though the letter calls for investigation, Abdullah-Span says “investigate” is a nebulous term. It is difficult to determine how many cases are investigated because the way an investigation is carried out varies case to case.

“But anything that’s reported, we respond to,” Abdullah-Span said. “Anything that’s reported.”

Jennifer thinks current laws work against sexual assault survivors.

“I don’t think women feel safe coming forward. I just don’t,” she said. “It can be embarrassing, and it’s just scary.”

The Dear Colleague Letter states that even if an individual does not want to move forward with a criminal investigation or with a disciplinary process, they must know that they are supported and have resources available to them, including the ability to drop a class or move residence halls if the alleged perpetrator is there.

“Everyone has to do what’s right for them,” Jennifer said. “If someone wants to report it, great. If it were to happen again today, I might do it differently, I might have reported it, but I don’t have regrets because it was what was right for me at the time.”

Prior to the Dear Colleague Letter, programs were put in place in an attempt to curb the rate of sexual assault, such as FYCARE, Abdullah-Span said.

“The hope with putting in place these mandatory programs for incoming students is that people are more aware and they’re making decisions that contribute to their safety and to reducing the number of sexual assaults that are occurring because when you’re better educated, you make better decisions,” Abdullah-Span said.

There is no way to gauge how effective the programs are because there isn’t an accurate number of the occurrences of sexual assault on campus, she said. But the programs are more than just educational tools. They are also a way for the University to convey that it is not going to tolerate sexual assault.

Although Jennifer says she’s biased, she believes FYCARE is an effective program to educate students on sexual assault.

“It clearly describes what sexual assault is,” she said. “(Survivors) might feel super uncomfortable after something, but they think that was normal. It’s not normal. That was sexual assault, and I think it’s important people know that.”

***

FYCARE helped Jennifer realize her attack was just that — an attack — something she hadn’t previously believed.

“I did not consent to it, he made me uncomfortable, he harassed me for weeks after. I sat in and cried by myself a lot,” she said. “It wasn’t normal.”

FYCARE also emphasizes supporting survivors, and with the high rate of assault on campus, Jennifer believes chances are that everyone knows someone who has been assaulted.

“We need to know how to be there for them and what’s the best way to support them in this time,” she said.

Jennifer is a FYCARE facilitator and said the class she had to go through to become qualified helped her cope. The first person she confided in with her story was Molly McLay, her teacher and the assistant director of the Women’s Resources Center.

She didn’t immediately tell her friends from home because they know her perpetrator, so she talked to her sorority sisters. This past winter break, Jennifer finally told two friends from home.

“I still didn’t tell them the name, but I did say if I ever found out they were going to hang out with this person, I would tell them,” she said.

At the end of her freshman year, Jennifer told her mom what happened while she was driving her back home. She was furious at the situation and the fact that Jennifer never took pregnancy or STD tests. Her mom made her get tested, and the results all came back negative.

“The pain that you feel when you go through a sexual assault is awful, and you don’t want anyone else in your family to have to feel bad for you or go through the pain with you,” she said. “It’s almost to protect your family and friends, too.”

Brittney can be reached at [email protected].