Survey uncovers sexual assault and harassment in scientific fieldwork

Sep 2, 2014

Last updated on May 11, 2016 at 03:07 a.m.

A recent survey found evidence of prevalent sexual harassment and assault of researchers performing fieldwork in studies like anthropology, archeology and geology.

The survey results show that 64 percent of survey respondents had been sexually harassed, and 21.7 percent had been sexually assaulted.

The survey was conducted after Kate Clancy, anthropology professor at the University, developed an interest in the topic from personal experience listening to stories about sexual assault and harassment in the field.

“I was talking to an old friend and trying to figure out why she was having difficulty finishing her dissertation … when she revealed to me that she had been sexually assaulted in the field,” Clancy said. “She actually tried to report the incident and was essentially not really believed.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Another colleague then confided in Clancy that she had been sexually assaulted in the field.

She published both stories anonymously on her blog two years ago, after which she said, “the stories just started pouring in.”

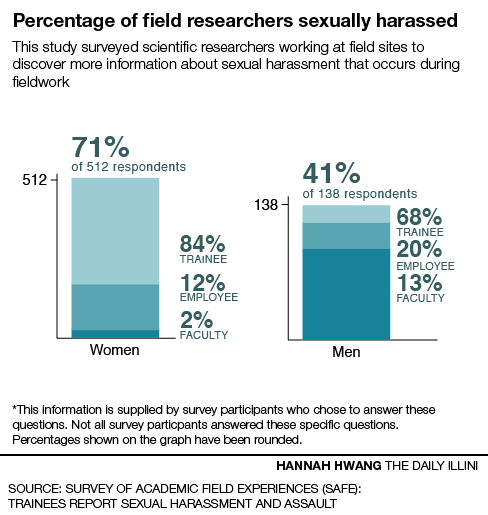

Out of survey respondents, 71 percent of women said they had been sexually harassed, compared with 41 percent of men. And 26 percent of women said they had been sexually assaulted, compared with 6 percent of men. However, not all participants chose to answer the question.

This survey included 666 participants and about 77 percent of them were women.

The study was authored by Clancy, Skidmore College Professor Robin Nelson, University of Illinois at Chicago professor Julienne Rutherford and Harvard University professor Katie Hinde.

Hinde expressed extreme emotion in reaction to the survey’s findings.

“Mostly I was very, very sad. That’s really the emotion you have when you start going through these data and seeing the experiences that people go through,” Hinde said.

A 2014 graduate from the college of LAS, who preferred to remain anonymous, confirmed that sexual harassment is present for women in scientific fields.

“While most women, including myself, might not recognize sexual harassment (even when we’re the ones being harassed), it’s definitely there,” she said in an email. “I’ve had guys joke to me that the only reason I’m doing so well is because I must be sleeping with the professor or make comments about how I’m dressed and how it’s not feminine enough.”

The same graduate believes women face numerous difficulties while engaging in scientific fieldwork.

“Because men have traditionally done fieldwork, it has evolved as an environment that isn’t really conducive to women,” she said. “Something as simple as taking a bathroom break or, god forbid, changing a tampon is suddenly exponentially harder when you’re surrounded by a dozen guys in the middle of a treeless, flat desert.”

The survey found that most of those harassed or assaulted were trainees. However, men were usually found to be abused by their peers, while women were often abused by someone higher up in their field.

Clancy said hierarchal abuse is incredibly detrimental.

“Evidence suggests that harassment and assault are psychologically damaging no matter what,” Clancy said. “But when the person doing it to you is superior to you in some way, or has some power over you, then the data suggests the psychological harm is far greater.”

The survey results also show that women respondents were 3.5 times more likely to report sexual harassment than men.

Tara McGovern, recent LAS graduate of the University, has experienced fieldwork in cultural anthropology and said it can be outright dangerous for female students.

“I hate to break it to all those aspiring young white suburban female anthropologists — you can only do this type of fieldwork safely if you are a male,” McGovern said in an email. “And even for males, I have my doubts.”

McGovern clarified that this problem is specific to the field, not the University campus, in her experience.

“No assault or harassment or anything of the like ever happened in my experience on campus,” she said. “Professors on campus are extremely careful and responsible; my criticism is that they are unaware of what can and does happen to an untrained vulnerable undergraduate in the field.”

McGovern personally knows many undergraduate women who were sexually assaulted while performing fieldwork and have consequently discontinued their fieldwork.

“The perpetrators were informants — members of the culture we were supposed to be studying, although there have also been cases of graduate students (not associated with the University) targeting undergraduate trainees,” McGovern said.

The study reports that local community members are also involved, but remain a minority in the studied cases of sexual assault of fieldworkers.

Although she does not yet have numerical data to support her claim, Clancy feels there is a possibility that these cases of assault and harassment are causing women to leave scientific disciplines.

“My suspicion is that … when women are experiencing this at a greater proportion and when the kinds of abuse they are experiencing are worse, or more psychologically harming, then the chances of them staying in that discipline are very much reduced,” Clancy said.

The study further revealed that in addition to sexual assault and harassment, oftentimes there is not a highly visible or satisfactory system for reporting the incident.

Clancy said that many scientists were told, “what happens in the field stays in the field,” as soon as they arrived.

In the survey, less than a fourth of the respondents recalled working at a field site where there was a sexual harassment policy.

Over half of respondents who reported sexual harassment and almost three-fourths of respondents who reported sexual assault in the field said they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the outcome of the report.

In the field, McGovern experienced several attempted assaults by informants and was dissatisfied with the way her situation was handled on campus.

“At first, I was told to ‘forget about it.’ Which I tried to do,” McGovern said. “It just seemed easier to pretend like it didn’t happen, that I was stupid and had provoked it myself. I believed that revealing that kind of information would make me appear vulnerable and irresponsible, as someone who was ill-equipped for the field.”

Clancy said that any field site that is associated with a university should be using the university’s code of conduct. She feels the larger issue has to do with the climate of the site.

McGovern said that many of these cases of harassment and assault could be combatted.

“I think a lot of these problems can be avoided with a couple of classes or workshops for departing researchers,” she said.

McGovern believes this study has the potential to give credibility to female scientists working in the field.

“Dr. Clancy’s publication has given me hope,” McGovern said. “When she says that she hopes the findings validate female scientists, she’s absolutely right.”

Alex can be reached at [email protected].