Low-income, minority students face achievement gap in Illinois

Jan 28, 2015

Last updated on May 10, 2016 at 10:32 p.m.

State legislators and educators are working to improve the quality of education among low-income students by closing the achievement gap.

The Illinois State Board of Education approved its fiscal year 2016 budget recommendation on Jan. 21, which seeks to increase General State Aid funding by $729.9 million. In a statement, Christopher A. Koch, Illinois state superintendent of education, said the increase could go a long way toward improving the quality of education for Illinois students.

“Education is the smartest investment we can make in the economic future of our state and the quality of its workforce,” Koch said. “GSA funds have fallen short of what is owed to school districts for the past four years, contributing to poorer financial health for more school districts and threatening the academic and extracurricular opportunities for the state’s two million students.”

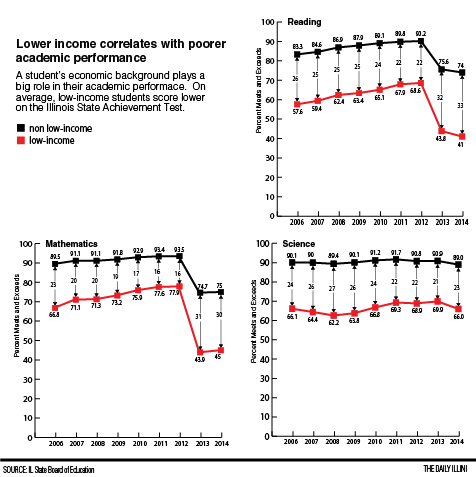

Koch’s remarks are a nod to a concept that has recently been a hot topic in Illinois politics: the achievement gap, or the academic disparity that exists between low-income and non-low-income students, as well as between minority and white students.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“We say we educate all kids, and we do, but we don’t give all kids the same public education,” said Eboni Zamani-Gallaher, professor in Education. “In those communities where there’s a higher property tax base, there are more options, and for those that are in communities (with less property tax revenue) … they have to do more with less.”

Data from the State Board of Education showed that in 2014 low-income students score significantly lower results on the Illinois Standard Achievement Test, ISAT, averaging 33 points lower in reading, 30 points lower in math and 23 points lower in science. According to the Illinois State Board of Education, 51.5 percent of students are considered “low-income” students.

Lorenzo Baber, assistant professor in Education, said students living in or near poverty face a number of challenges that can have detrimental effects on classroom performance, as well as on standardized tests. These students face higher levels of test anxiety, Baber said, out of fear that if they do not receive high marks, their career and higher education opportunities will be severely limited.

“For a lot of these tests, you can increase your scores by taking courses outside of class, and of course for low-income students, they don’t have as much access to these additional classes outside of the traditional school, and that can have an impact on their test scores,” Baber said.

Low-income children also have less access to the health care they need to help them succeed in school, like prescription glasses, Zamani-Gallaher said. The obstacles facing children living in poverty can have a “snowballing effect” and lead to chronic problems throughout their education, she added.

For black and Hispanic students, who are more likely to live in poverty than whites, these problems are even more pronounced.

“We have seen where, particularly depending on race and ethnicity interacting with socio-economic status, that there’s a broader achievement gap,” Zamani-Gallaher said. “When we look at the poverty statistics in terms of what is proportionate, you see a disproportionately higher number of black children, of Latino children that live in poverty, and they’re more likely to attend schools that are not funded as well.”

The disparities between the ISAT scores of white and minority students mirror the gap between low-income and non-low-income students, with lower average scores in reading, math and science.

Newly-appointed State Board of Education Chairman James Meeks said closing the achievement gap is his top priority. In a Jan. 10 Chicago Tribune piece, Meeks was quoted stating charter schools and education vouchers as potential solutions to the problem.

However, Baber and Zamani-Gallaher are skeptical to these approaches. Charter schools, which are publicly-funded but typically comprised of students with similar demographic characteristics due to their geographical compactness, are largely unproven to provide a higher quality education, Baber said.

“Most of the evidence on charter schools is at best anecdotal,” Baber said. “There’s really not any true experimental designs that isolate charter schools as being ‘better’ than public schools.”

Zamani-Gallaher said while education vouchers may seem like an appealing approach to closing the achievement gap, low-income students will still face significant limitations on their schooling options.

“Vouchers are not a panacea, particularly if you’re trying to benefit low-income students and students of color,” Zamani-Gallaher said. “These are publicly-funded scholarships that students can use for private school tuition, (but) for many families that are living in poverty or students that are not from affluent households, the vouchers still don’t go the distance in being able to provide parents with private school options.”

Closing the achievement gap is such a pressing matter, Baber said, because of the widespread benefits that an educated population has on society as a whole. He added that giving students the opportunity to move on to higher education will keep Illinois viable in the global economy.

“College-educated citizenry are more employable, less likely to engage in high-risk health behaviors, which decreases your health costs, and are less likely to participate in any criminal activity,” said Baber. “If you want to decrease health care costs, if you want to decrease the cost of incarceration, education is the ladder you should focus on.”

Josh can be reached at [email protected].