University researchers see progress with new cancer drug

Apr 8, 2015

Last updated on May 10, 2016 at 07:47 p.m.

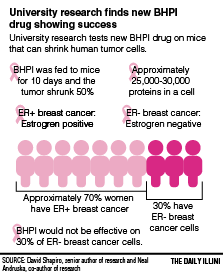

A group of M.D. and Ph.D. students and professors at the University recently found successful results in treating breast cancer cells in mice with the new drug BHPI.

The BHPI drug is currently in the preclinical trial, said David Shapiro, senior author of the research project and biochemistry professor. The team hopes to move the research forward into the clinical stage as rapidly as possible where they will be able to test it on humans and introduce it to the medical field.

Neal Andruska, lead author of the research and M.D. and Ph.D. student, said the team wanted to try to identify possible drugs that would be effective on cancers and tumors already resistant to traditional therapies. He said this research began approximately six years ago.

“Estrogens play an important role in cancer and they promote the proliferation of breast cancer cells and for that reason a lot of cancer drugs have been developed to target estrogen’s actions in cancer cells, called anti-estrogen drugs,” Andruska said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The team took a different approach to identifying a drug candidate, Andruska said.When drugs are being developed, most people think of a certain protein that would target the cell and kill it. However, the research did the reverse; the team identified something that worked well in the cells first, and then determined how that overpowered drug-resistant cells.

“Most people who do cancer studies, they don’t actually grow the tumors first,” Andruska said. “We actually grew out breast cancer tumors in mice and then we began feeding it with our compound, which we call the BHPI.”

Lily Mahapatra, team member and M.D./Ph.D. student, said human cancer cells were put in mice to mimic what doctors would observe in a patient.

Andruska said in ten days the treatment blocked the growth of cancer cells and prompted tumor regressions, shrinking the tumor by 50 percent.

“The compound is effective in animals,” Andruska said. “In ten days it induced tumor regressions. It actually stopped growth of tumors.”

Xiaobin Zheng, second author of the research and M.D./Ph.D. student, said the cancer cells need to contain estrogen receptors for the BHPI drug to work.

Zheng said the team had to overcome non-toxicity, which was a major test.

“Other drugs you see in the clinical market have to pass the toxicology, which means they do not show adverse effects in (mice),” Zheng said.

Andruska said the mice tested in the study showed no signs of overt toxicity.

The tested mice did not lose weight and food intake was consistent. With that, Andruska said, the results were promising, yet they would still need to perform more toxicity experiments.

“There are many questions that need to be answered before we can test the compound in cancer patients,” Zheng said. “For example, we have to test the compound in mice. We also have to show the compound is not toxic to non-tumor cells.”

For the team, Zheng said understanding the mechanism underlying the drug’s function was a major undertaking for the past few years.

“We are excited to see the outcome of the BHPI and all the testing results we got from the cell and animal studies,” Zheng said. “We urge to do more animal studies in near future.”

Mahapatra said going from the tissue culture plate, then going to mice and eventually having an ultimate future direction of going into clinics is the overall gamut of the research.

Andruska said BHPI both blocks growth of preexisting tumors in mice and induces rapid tumor regression and does not display overt signs of toxicity. However, there is still more research to be done for this drug to appear in human clinical trials. Shapiro said finding the proper drug dosage to be tested is also necessary before moving to clinical trials.

“We are still a long way off from putting this compound into actual patients, but we are very optimistic that BHPI can overcome the many challenges ahead,” Andruska said. “BHPI has already cleared many hurdles by a wide margin.”