Study Finds Rebates an Effective Way to Improve Health Among Low-Income People

Nov 1, 2015

Last updated on May 5, 2016 at 07:53 p.m.

The study was based on a USDA report of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP). The pilot was a large-scale randomized trial conducted in 2011-2012; it provided 30 percent rebate on targeted fruits and vegetables to 7,500 study participants enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

“Recently there’s been research suggesting that providing a discount or rebate for people to purchase healthy food may encourage people to adopt healthy dietary behavior,” An said.

However, he said promoting or reducing obesity is not SNAP’s main focus.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“The main purpose of the SNAP program is not to reduce obesity but to provide low-income families with the food they need to reduce the malnutrition and nutrition deficiency and increase food security,” he said.

Still, An conducted his study as a means to determine the cost-effectiveness of the expansion of the HIP program to all SNAP participants nationwide.

Through his study, An found the rebate would increase the SNAP participants’ scores 0.08 on the quality-adjusted life year scale. The quality-adjusted life year, or QALY, scale is a measure of the quality of life of an individual within one year. If the individual is in perfect health they would receive a one on the QALY scale, while a person in extremely poor health would receive a score between zero and negative one.

The QALY is also the unit used in assessing the value for money of a medical intervention.

An’s calculations predicted the program has a cost-effectiveness ratio of $16,172 per QALY gained, which is relatively cheap considering the threshold is often $50,000 to $100,000 per QALY gained in the U.S.An estimated the rebate to cost the federal government $1,323 per person on the program.

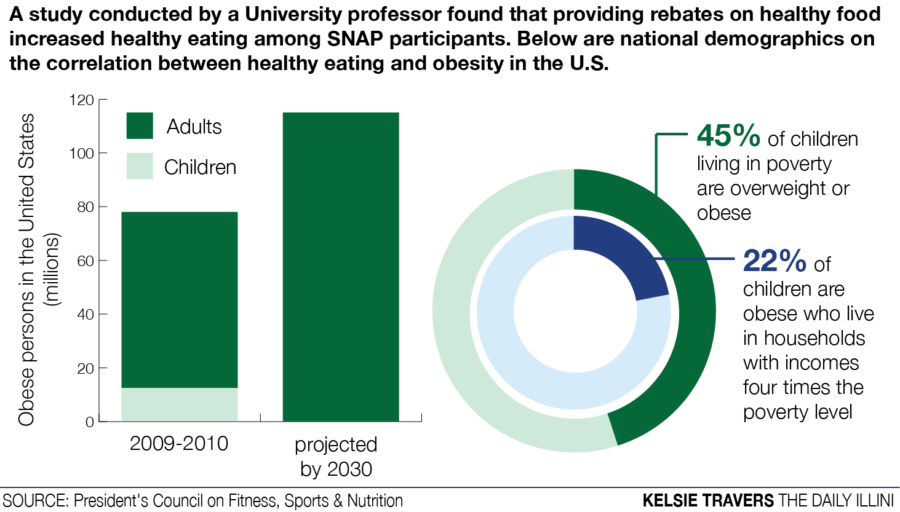

According to a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, SNAP participants are 10 percent more likely to be obese than higher income nonparticipants.

An said one explanation for the higher likelihood of obesity in low-income people is that high-calorie junk food tends to be less expensive than healthy options.

There is strong evidence that this awareness of price contributes to obesity, he said.

While college students may not be in the same situation as those income-eligible SNAP participants, a study published in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior found that 59 percent of students at a mid-size university in Oregon were food insecure at some point during the previous year, meaning they had limited or uncertain access to nutritious and safe foods.

Vaughn said not a lot of students on campus have a lot of money to spend, which is why she thinks places on campus like County Market don’t have a wide variety of healthy foods. Paige Vaughn, sophomore in LAS, said price often influences what she buys.

“I usually, and unfortunately, buy unhealthy things because they are much cheaper,” she said.

While there are other components of SNAP that encourage healthy eating, such as collaboration with farmers markets, An’s micro-stimulation specifically shows the impact of cost incentives.

“The bottom line is that a price incentive is progress — but not a silver bullet,” An said.

An said the incentive is still low and that a rebate of 30 percent can only change people’s dietary behavior a small amount because people’s behavior will change proportional to price.

Still though, An is positive about its implications.

“A subsidy is the better choice because it’s a step in the right direction,” he said.