The Chief: An unspoken presence

Nov 8, 2015

Last updated on June 14, 2016 at 08:30 a.m.

Ivan Dozier is trying to recover a tradition at the University of Illinois.

A tradition forgotten by some, a tradition the Champaign-Urbana community and a network of alumni will never forget or accept its loss, and one that many University students rarely give a passing thought these days.

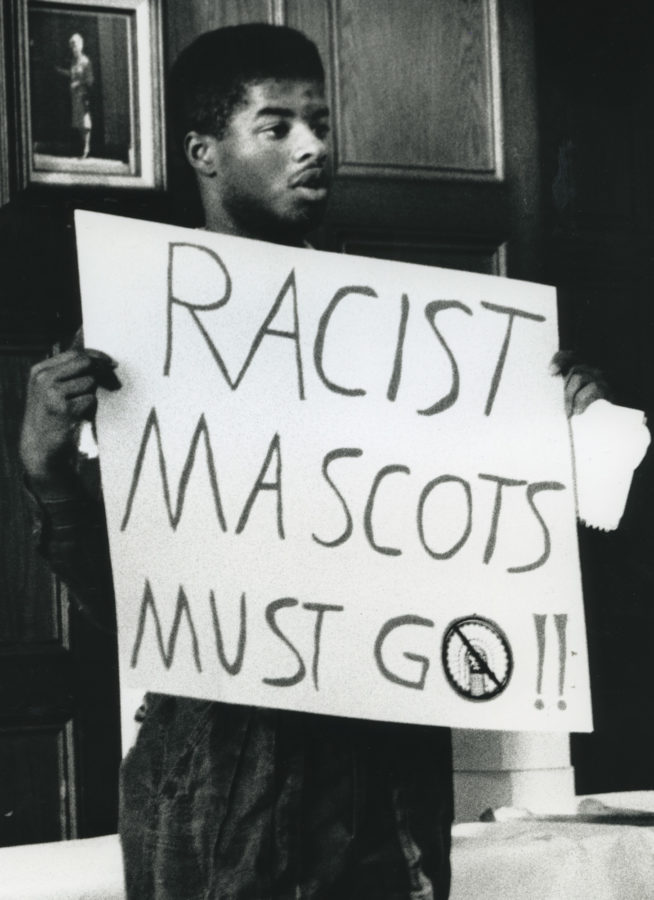

It’s also a tradition that others find offensive, ignorant and embarrassing.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

But Dozier wants it back. He wants the Chief back.

Eight years after the University’s decision to ban Chief Illiniwek and after the last halftime dance at Assembly Hall, Dozier, the current “unofficial” Chief and a graduate student in Crop Sciences, is continuing its legacy on campus along with other pro-Chief groups.

As the unofficial Chief, Dozier makes appearances in the regalia in the stands at football games and at events like the Homecoming Parade. He was even invited to the funeral of a C-U local whose dying wish was that the “Three-in-One” be played and everyone yell “Chief” at her service. He also works with the Council of Chiefs, made up of past Chief portrayers, to think of ways to bring the tradition back officially. But after five years as the Chief, Dozier’s term is coming to an end — he is graduating in December. This means he has to choose a new person to continue its 89-year history.

Starting in September, he heads to tryouts every Thursday on the South Quad, where the Chief and the band used to practice. Currently, there are three students trying out, and two will receive positions, one as Chief #39 and another as an “Assistant Chief.” Dozier and the Council of Chiefs hope the new unofficial chief will be more of a spokesperson and educator for the University.

But what sets Dozier apart from portrayers of the past is his Native American heritage. He is part Cherokee. The only other Chief portrayer with Native American ties was back in 1943, when Idele Brooks, who grew up on the Osage Reservation in Oklahoma, became the first and only female Chief.

Dozier wanted to be the unofficial Chief because it was something that honored the University.

“I always thought the Chief was very dignified, the tradition and the way that people viewed the Chief was always in a very positive light and a very proud light,” Dozier said. “The Chief was different than a school mascot. The Chief was a symbol. … I always thought that was something that made the University special.”

An undisputed controversy

Dozier wasn’t always as strong in his convictions about the Chief. He explained that one of his cousins, a University alumnus, was part of the anti-Chief movement on campus. Within his own family, both sides are represented. Dozier was aware of this divisive topic right away, and he wanted to form his own opinion when he arrived on campus as a freshman in 2009.

“I was both a member of Students for Chief and the Native American House as a freshman,” he said. “I really wanted to immerse myself in both (of) those worlds and kind of see what both sides were — what their views were … before I really made a decision on what it is I wanted to do and what it is I believed.”

When choosing the new portrayer, Dozier said Native American heritage is not necessarily a requirement. He said the most important thing is that they are knowledgeable about the culture.

“One of the things I like most about the Chief tradition is that it is open to any student, regardless of race or gender, so I think that is important for the Chief, as a symbol of campus unity, the fact that it could be any one of us out there,” he explained.

But Dozier doesn’t neglect the inaccuracies surrounding the Chief. For example, the dance and costume are derived from the Ogalla Sioux, meaning they don’t relate to the Illiniwek tribe’s closest living descendants, the Peoria Tribe in Oklahoma.

He said he also believes other mascots gave the Chief a bad name.

“I think that may be one way people get confused and get offended,” Dozier said. “They look at another mascot and say, ‘Oh, well look at that joking around and falling over, and you’re representing a culture by joking around and making fun of it.’ Intention does matter.”

A new era

When the mascot becomes more of a spokesperson, Dozier and the Council of Chiefs hope some of the controversies will be resolved.

Steve Raquel, an adjunct lecturer in the College of Business and member of the Council of Chiefs, served as the Chief in 1993. Back then, Raquel said the job’s emphasis was 80 percent on dancing and 20 percent on persona — meaning speaking with University coaches, alumni, students and other groups.

“Now it is probably 80 percent persona because you’re still communicating the tradition, you’re still talking to group (and) you’re still defending the tradition and getting out in front of the public,” Raquel said. “As we look at tryouts, we definitely want someone who is going to dance, do great in the regalia, but more importantly, what kind of person he is (and) do they represent the tradition well.”

Raquel said these steps could officially bring the Chief back. To do this, he said, they first need the approval of the Peoria tribe. According to the NCAA, if an individual plans to portray a tribe, he needs to get the tribe’s permission. Since the Peoria tribe is the closest living descendants to the Illiniwek, they make the call.

In 1995, Peoria Tribe Chief Don Giles said he supported the Chief as the University’s symbol. But five years later, the new Peoria Tribe Chief Ron Froman said he opposed it because it “does not accurately represent or honor the heritage of the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma and is a degrading racial stereotype that reflects negatively on all American Indian people.”

Raquel said he believes they have cultivated a relationship with the Peoria Tribe over the years and could get their permission again in the future. However, Raquel recognizes that this is hard to do since the Chief’s regalia and dance are based on a completely different tribe.

“When you go to the Peoria tribe and say, ‘Hey endorse this regalia and dance that has nothing to do with you,’ they look at us and go, ‘Why? You’re telling me to say that’s a Ford when it is actually a Chevy,’” Raquel said.

However, he said he believes that if the Council of Chiefs can figure out a way to make the look, the feel and the dance better aligned with the Peoria tribe, they have a better chance.

Bennett Kamps, sophomore in LAS, is trying out to be the next unofficial Chief. Kamps said he has wanted to audition since childhood, and he heard about the tryouts at the Students for Chief Illiniwek booth at Quad Day.

“Everybody in my family went here, so I grew up in a house that was always orange and blue,” Kamps explained. “To be the symbol that represents everything here that I love, where I’ve got my best friends, where I’m going to get my job from, it’s just a big opportunity, and I want to get that.”

If elected as the unofficial Chief, Kamps said he is aware of the challenges he will face.

“Well, obviously, the Chief was banned because it is politically incorrect, so one of the biggest challenges I think I’m going to face is people calling me a racist and not understanding it,” he said. “I actually do respect the symbol. … It’s become a symbol of our school, and it’s developed into a culture at U of I… I’m actually just respecting my University.”

A wake up call

While many groups dream of the Chief’s new era, some people think they need to wake up.

Jay Rosenstein, a Media and Cinema Studies professor and American Indian Studies affiliate at the University, said continuing the legacy of the Chief, even unofficially, has a devastating impact on Native American students, faculty and the University as a whole.

“It’s something that is extremely offensive. It is something that is ignorant,” he explained. “It is something that runs counter to everything that public universities are supposed to stand for, which is to be a place that is inclusive of all people. It is also something that I think is an embarrassment to a place that claims that education is its first priority.”

Rosenstein is most famous for his 1997 documentary “In Whose Honor? American Indian Mascots in Sports,” which helped lead to the NCAA’s decision to ban Native American mascots and imagery and is used as an educational tool at colleges and universities across the country.

Rosenstein said constant reminders of the Chief impact his two children as well. Even when he takes his daughter to women’s gymnastics meets, the presence is felt when the band plays “Three-in-One,” causing people in the stands to walk around with their arms folded and yell “Chief.”

However, Rosenstein said his children, who are 11 and 15, are used to this, even when their schools have “Illini Day” and the students wear Illini gear that often perpetuates racial stereotypes.

“You know, my kids understand it,” he said. “In fact, an 11-year-old can understand it very easily. Unfortunately, a 60-year-old man who spent his whole life in Champaign-Urbana can’t.”

Rosenstein said his overall impression of Native American culture on campus is that it is essentially absent. One of the only reminders for students is the Native American House on Nevada Street in Urbana. The Native American House declined to comment on this story.

“There’s probably no more than 10 or 12 legitimate American Indian people in a town of 100,000,” he said. “All you see is these sort of phony, made-up, fake Native American culture. But there is no real culture that has any presence here.”

Professor Emeritus Stephen Kaufman, a well-known Chief opponent, added that it is important to remember that Dozier and the Council of Chiefs do not have any rights to the Chief, as these are held by the University. He explained that University leadership needs to remind them and the public of this.

Kaufman also wrote in an email that while supporters have the right to dressing up as the Chief because of the First Amendment, the University needs to enforce their property rights.

“Let’s hope that the new team, Chancellor Wilson and President Killeen, will rise to the occasion and provide the leadership the institution deserves,” he wrote. “If students appeared as a rabbi, the Pope, in “blackface” or as a Nazi soldier, the administration would rightfully speak out. This is no different; genocide is genocide is genocide.”

Kaufman also acknowledged that change can be hard for people to accept. However, he explained that the country has moved on and it’s time for the campus to do so as well.

“All social changes in this country were met with pushback from people who strongly identified with or felt a loss by the imposition of such changes,” he wrote. “Change challenges the decisions people have made by which they lead their lives and some people find this very difficult to accommodate.”

Educating the masses

But despite the massive differences between the two groups, both seem to agree on one thing: There is a desperate need for education about Native American culture on campus.

Dozier said the Chief is instrumental in this.

“I think the education with this issue is very important and people (need to) understand why this is a divisive issue, and I think that the Chief needs to continue to be out there to provide that source of education,” he said.

However, Rosenstein questioned the methodology of pro-Chief groups like Students for Chief and the Council of Chiefs. Even though Dozier has Native American heritage, many members do not.

“So in other words, a person who has no native background and no expertise in native culture is going to lead an education effort at a degree-granting university?” he said. “That’s a really interesting idea. I should go around and give lectures about nuclear physics because I like it.”

Whether the tradition of the Chief is a symbol of pride or ignorance, Dozier is trying to recover it.

In the meantime, he asks that people consider both sides of the issue.

“I think the important thing to realize about open mindedness or at least what being in this role taught me is that open mindedness is not a static condition. You are never just an open-minded person, written in stone, solid; Being open-minded is a constantly active pursuit.”

Clarification: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Jay Rosenstein is a journalism professor at the University. The article should have stated that Rosenstein changed departments this year and is now a professor of Media and Cinema Studies. The Daily Illini regrets the error.

View a timeline of the history of the Chief.

Compiled by Annabeth Carlson, assembled by Steffie Drucker