University increases African-American enrollment, some still skeptical

Sep 21, 2016

Last updated on Sept. 23, 2016 at 02:41 p.m.

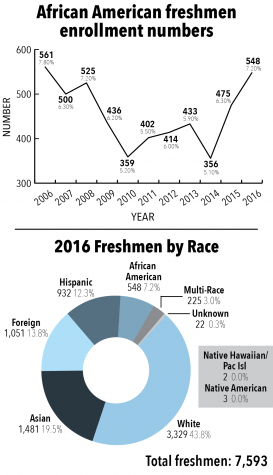

There are more African-American students enrolled at the University this semester than there have been in the past decade.

There are 548 African-American students enrolled this fall; the number is 13 shy of the 561 students enrolled in 2006, according to enrollment data.

There are 73 more African-American freshmen, or 15 percent more, this year than in 2015. The students account for 7.2 percent of the freshman class, and they accounted for 6.3 percent of last year’s class.

The University has touted this year’s freshman class as the largest and most diverse ever, but some remain skeptical.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Ron Lewis, student body president, said he thinks it is easier to boast percentages, but the actual number shows less improvement. And even with the change, he said, African-American students still represent 5.2 percent of the entire student population.

“That’s one thing you also have to tackle is just realizing that, you know, although it changed,” he said, “proportionally that’s what it should be whether it was increasing or not.”

Associate Chancellor for Public Affairs Robin Kaler said in an email that students from underrepresented, low-socioeconomic statuses traditionally have not accepted admission offers at the same rate as the rest of the prospective student populations. To combat this, Kaler said the University increased its efforts to recruit and enroll students from these groups.

Gigi Secuban, associate vice chancellor for student affairs and director of the Office for Inclusion and Intercultural Relations, credits her office’s African-American high school students recruitment events for helping, too.

Seniors visited campus in February to meet students, faculty and staff and participate in the annual Cotton Club variety show. Juniors visited campus in May and attended the spring football game. The University bussed down these students and their families from the Chicago area, Western Illinois and the St. Louis area, according to Secuban.

“It’s going to be a continual effort, and it’s going to take working with alums, working with the schools — the public schools — (to) continue to build those relationships and continuing to encourage students to come to campus and see what campus life is like here,” she said.

She thinks the events effectively boosted enrollment numbers, but she does not think the University should stop its efforts there.

“I don’t think we can ever settle and say, ‘OK, we’re at where we need to be,'” Secuban said.

Enrolling more minority students has been a focus for the University since 1968 after students pressed the issue. That year, the University admitted 565 African-American and Latino students as part of the Special Educational Opportunities Program, or Project 500, according to University archives.

These efforts, though different, still continue today. But in the past 10 years, African-American freshmen enrollment has hovered between 356 and 561 students. Hispanic enrollment has grown more, with figures between 457 and 932 students in the same period.

Tekita Bankhead, assistant director of the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center, hopes the University can reach the point where it does not need to celebrate slight improvements.

“I want us to get to a place where it’s not out of the ordinary to have African-American students that are enrolled at one of the top ranking institutions in the world,” Bankhead said.

Savon Coleman, freshman in DGS, debated whether to attend a historically black college or university or a predominantly white institution, a university where whites account for 50 percent or more of enrollment. Her decision ultimately came down to financial aid, and she is “very happy” with it.

One month into her freshman year, Coleman said she has made friends of all races.

“The whole purpose of college in general is to learn more about everything, so that’s something you should definitely take into your social encounters,” Coleman said.

Javion Holman, freshman in LAS, has wanted to attend the University since his kindergarten teacher raved about it. Some of his friends did not share his enthusiasm. Holman said some of them did not even bother to apply to the University.

“I feel like this school is predominantly white, so when people think about this school they don’t apply because they know like, ‘Oh, well we might not get in because we’re African-American and that ain’t worth it for us,'” Holman said.

Holman thinks the University should advertise more that it accepts all races and work to “make people feel more comfortable.” He would like to see more African-American students because it would make campus feel more inclusive, but it “doesn’t really bother” him that there aren’t more now.

Noah Williams, freshman in DGS, said he notices the lack of African-American students on campus every day. He attended an Urban Prep Academy school, an all-African-American male school in Chicago, so attending a diverse school is a new experience. He does not feel out of place, but said minorities always experience uncomfortable or awkward situations.

“For me personally, coming from a 100 percent all-black school, like I said, if I go into like a dining hall, something like that, and everyone around me is like Caucasian people, Asian or people of other races, I rarely see black people,” Williams said. “It’s a comfortability issue for me because coming from an all-black school, and I’m the only black student.”

Williams said he has adjusted to the campus’ racial makeup, and he has made friends of other races on his dorm floor and in classes. But he does think making friends with other African-American students can be easier since they have shared experiences and cultural connections.

Lewis thinks it is important for minorities to feel like they belong on campus. As a senior in business, he has been the only African-American student in some classes. Of the college’s 4,195 students, only 131, or 3.1 percent, are black.

Being the only African-American has sometimes led to awkward classroom situations for Lewis, such as being the last one picked for a group project. Scenarios like that cause him to think generally, African-American students are not comfortable on campus because they worry about being judged or feeling like they don’t fit in.

“It’s a very hard conversation to have when you talk about inclusion and diversity, and I think the administration is starting to have those hard conversations,” Lewis said. “But we’re definitely not where we want to be in the fact that all African-American students could say, ‘Oh, we’re comfortable at the University.”’

Lewis praises Inclusive Illinois’ efforts and 100 Strong, an African-American cultural center program to connect freshmen with older students. Incoming students choose if they want to participate in the program and about half of this year’s class are participants, according to Bankhead.

But Lewis thinks more can be done.

As student body president, he wants to connect different organizations, departments and communities to develop meaningful diversity initiatives, then track their progress to identify effective strategies.

He thinks if the student government and the administration can do that, they will not only recruit more African-American students, they will also retain more of them.