Criminal history question may be prohibited from admissions process

Apr 26, 2017

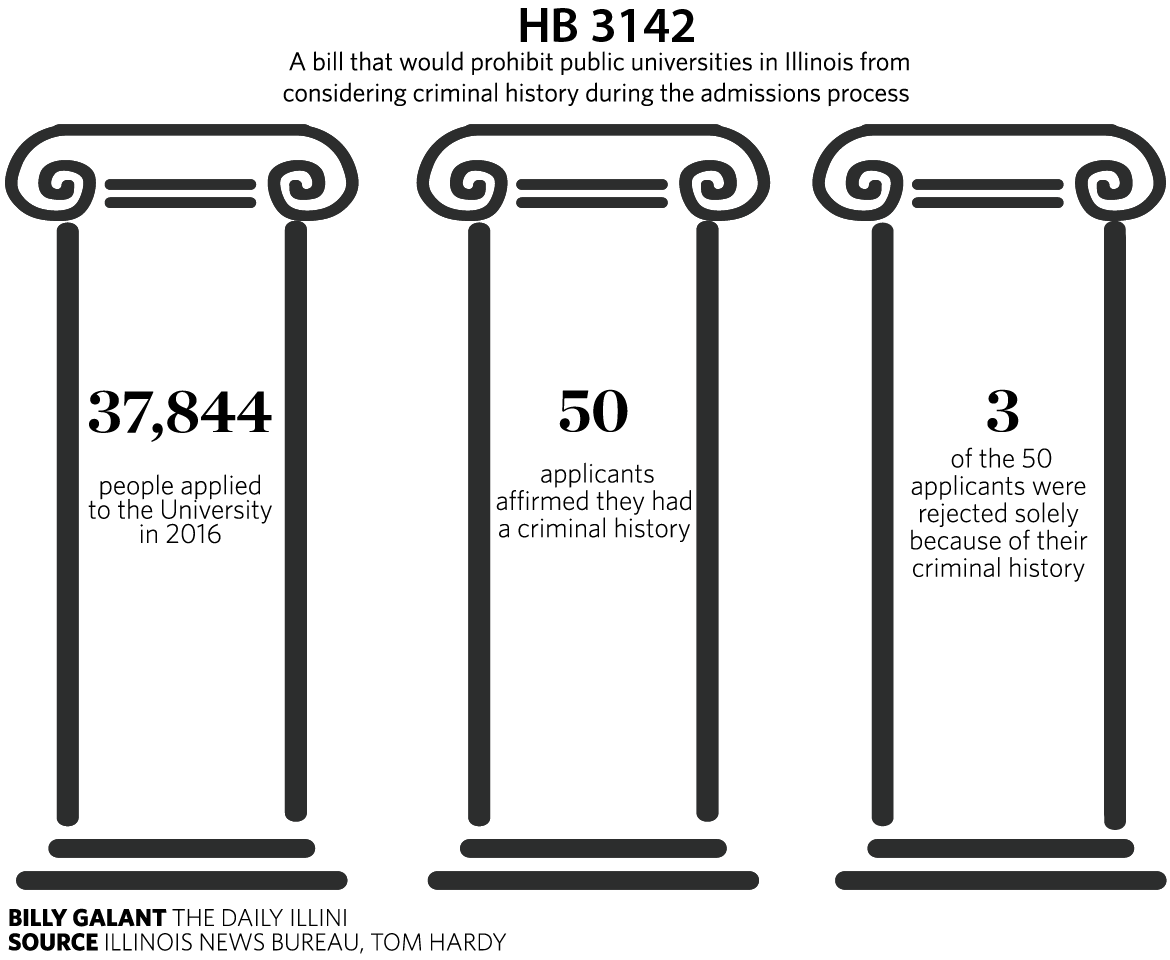

Public colleges and universities in Illinois may soon be prohibited from considering criminal history during the admissions process. The Criminal History in College Applications Act, HB 3142, has been passed by the Illinois House and is awaiting Senate vote.

Many college applications, including the Common App and the University’s, have a simple yes or no checkbox asking whether the applicant has been convicted of a misdemeanor or felony.

“We are, like the other public universities in Illinois, in opposition to this particular piece of legislation as it’s currently written,” said Tom Hardy, executive director of University relations.

Rep. Barbara Wheeler, chief sponsor of the bill, said the use of criminal justice information affects three populations: those who do not submit an application because of the question, those who do not complete the application because they fail to respond to follow-up inquiries about their criminal history and those who are rejected because of their criminal history.

For the three populations, the use of criminal justice information acts as “a barrier” to higher education, Wheeler said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“If a person (with a criminal background) is applying to college, then obviously they want to move on with their life,” said Rep. LaShawn Ford, co-sponsor of the bill. “I think it’s irrelevant whether or not a person’s been convicted of a crime to justify if they should go to college.”

The main source of resistance to the bill, Ford said, is the concern of how it might impact campus safety.

However, according to a study by the Center for Community Alternatives, no link between admitting students with prior convictions and decreased campus safety has been established. The study found that the 38 percent of responding schools that do not consider criminal history during their admission process do not have a higher rate of crime on their campuses.

“The question is, are people going to college to commit crimes?” Ford said. “I don’t think so. People aren’t spending hundreds of thousands of dollars and going into debt to commit crimes.”

Wheeler said current admission practices that consider criminal justice information impact those who do not complete their application because of the question the most.

A U.S. Department of Education report in May 2016 urged colleges and universities to remove the question on grounds that it could negatively impact potential applicants, deterring them from following through with the application process.

“It’s been proven with job applications that once a person discloses that they’ve been convicted of a crime, their application is often tossed in the garbage,” Ford said. “The chilling effect spills over to universities and colleges as well.”

Currently, the University system considers criminal history as one of many factors, said Robin Kaler, associate chancellor and director of public affairs.

“A prior conviction means that the University will scrutinize the applicant more closely,” Kaler said. “However, just as no single factor is sufficient to determine whether a student should be admitted, a conviction alone does not necessarily keep a student from being admitted.”

Hardy said the University makes it clear on the application that a prior conviction is not a hard line criterion.

“There’s a holistic process that the University uses when considering whether or not to admit somebody,” Hardy said. “[The act] would take away the ability to use that holistic approach.”

In regards to those refused admission because of their criminal history, Wheeler said she believes that such decisions represent additional penalties of crimes that are already accounted for through their served sentences.

“When you serve time, this is a direct consequence,” Wheeler said. “You’ve done your time in the justice system, but now, for the rest of your life, you’ll have collateral consequences.”

Although it is difficult to measure how the use of criminal history information impacts those who do not complete the application process, Hardy said that, last year, of the 50 applicants that checked the box for having a criminal history, only three were rejected because of their criminal history.

The consideration of criminal history during the admission process is performed by a special committee, Kaler said. If an applicant is rejected based on their criminal history, the decision can be appealed.

While the proposed act would prohibit colleges from making these considerations, it still allows colleges to consider an admitted student’s criminal history in making decisions about aspects of campus life like housing and participation in activities.

“I truly appreciate what the colleges are doing, that they’re concerned with campus safety,” Wheeler said.