University salary competitiveness continues to decline

Sep 28, 2017

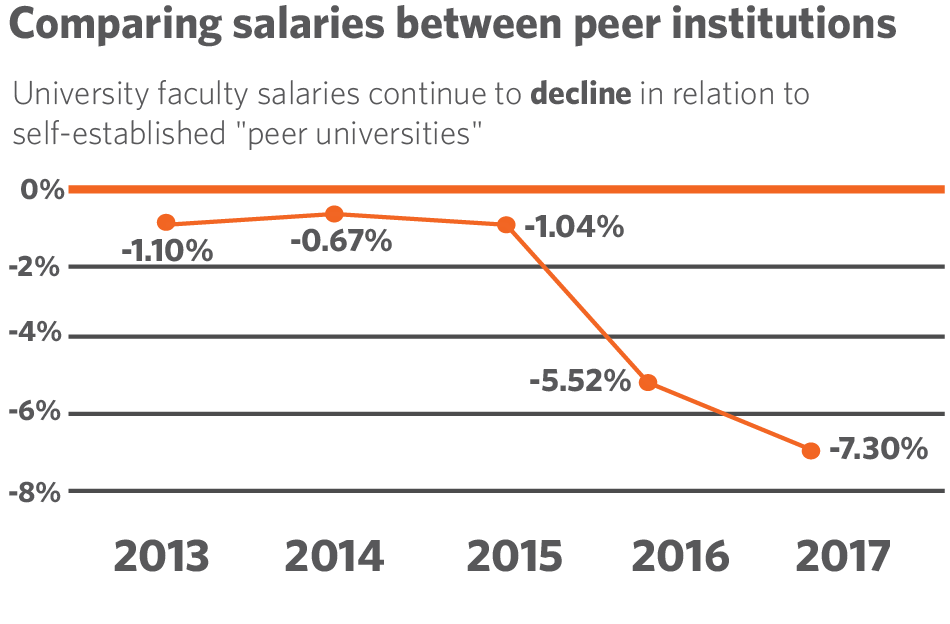

After reporting performance metrics at a Board of Trustees meeting on Thursday, Sept. 7, the University revealed average faculty salaries continued to decline in the 2017 fiscal year in relation to the school’s self-selected “peer universities.”

University officials select universities to be “peer universities” based on their institutional structure, academic standards and comparable faculty and research.

Data within the performance metrics showed a continuing decline in the University’s average faculty salary from about five percent below its self-selected peer universities median in 2016 to about seven percent in 2017.

Additionally, the University reported that the number of job offers made to its tenure system faculty in the 2016 fiscal year was higher than it has been since 2012.

University spokeswoman Robin Kaler wrote in an email that the University understands its current position and cites insufficient state funding as a primary cause.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“We are trying to be proactive in retention offers — despite the budget constraints we continue to face,” said Kaler. “Specific salary decisions are made at the department and college level, but our overall goal is to do all we can to retain our world-class faculty.”

David O’Brien, a long-serving professor in the School of Art + Design, said the University’s decline in competitive salaries is noticeable.

“It’s a problem,” said O’Brien. “(Faculty) have been leaving for higher paying jobs. There have been more people leaving (the University) as our salaries have fallen behind other institutions than were leaving prior to that. There’s just an obvious correlation.”

O’Brien said that the School of Art + Design has had faculty leave for universities such as the University of Notre Dame and the University of Southern California.

“They’re going to places that they wouldn’t have gone to 10 years ago — let’s put it that way,” he said. “They may not be as highly rated in my field as the University of Illinois, but you can essentially do the same research at those places. They were promised, I’m sure, equal research resources.”

Source: University of Illinois Board of Trustees

O’Brien noted that money isn’t the only factor in a professor’s career decisions: research opportunities and resources weigh heavily if not more.

“You don’t see so many people leaving here to go to small colleges,” he said. “And a lot of people wouldn’t even take a big pay raise if it meant going to a place where it was harder to do research.”

O’Brien said the effects of state budget issues trickle down to a state professor’s research.

“There are increasing regulations about how you can spend money (for research),” he said. “You have to fill out more forms. You have to wait longer to get bills paid. There’s also less money around to do research. So, it does in some ways impinge directly on your job.”

However, O’Brien acknowledged that money motivates a professor’s career decisions much like any profession when presented with two comparable jobs.

“Money can make a difference,” he said. “Perhaps money motivates professors less than in other professions, but, nonetheless, I think most people would rather have more money than less money.”

The University system made two modest efforts to raise faculty salaries across all Illinois campuses in 2016-2017 with a two percent merit-based salary program instituted in February of this year, along with an additional one percent increase to also be reflected in faculty’s September payroll.